INTRODUCTION

A Cold War Necessity

There is a certain feeling of courage and hope when you work in the field of the air. You instinctively look up, not down. You look ahead, not back. You look ahead where the horizons are absolutely unlimited.

Robert E. Gross, Lockheed Chairman/CEO 19321961

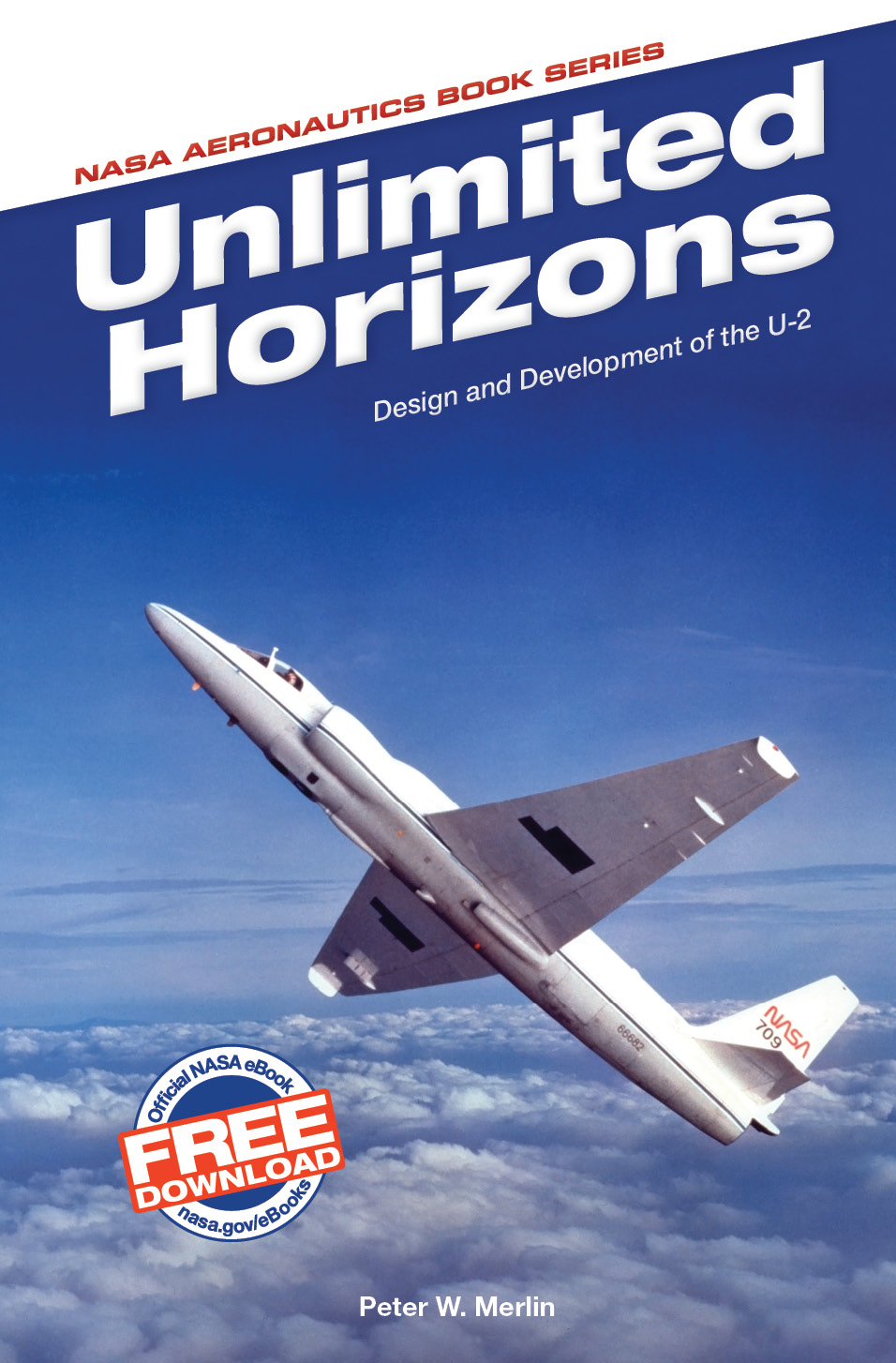

On a summer day in 1955, ominous clouds darkened the skies over a remote desert valley in the Western United States, reflecting international tensions between the U.S. and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In what had become known as the Cold War, the two superpowers vied for supremacy in the wake of World War II, waging a high-stakes game of brinksmanship as each strove to discover the others strengths and weaknesses through overt and covert means. The next bold step for the U.S. involved a spindly silver airplane, innocuously designated U-2, undergoing preparations for its maiden flight in the skies above central Nevada. Although this event took place without fanfare and in utter obscurity, it heralded the beginning of an aeronautical technology program that spanned more than six decades and showcased innovative aircraft design and manufacturing techniques. Little did anyone realize at the time that what had begun as a tool of Cold War necessity would evolve into a versatile reconnaissance and research aircraft.

The U-2 program originated with a national requirement, an unsolicited proposal, and studies championed by a panel of notable scientists tasked with advising President Dwight D. Eisenhower on how the Nation might defend itself against the threat of a surprise Soviet nuclear attack. To do this required as much intelligence as possible on Soviet capabilities, but the Russian-dominated USSR was a closed society that was virtually inaccessible to the outside world.

The most promising avenue toward solving this riddle was through observation from high above. In a November 1954 memorandum to Allen W. Dulles, director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Dr. Edwin Land, founder of the Polaroid Company, advocated for development of a reconnaissance aircraft to be operated by the CIA with Air Force support. The vehicle, already under development by Lockheed Aircraft Company, was described as essentially a powered glider. It would accommodate a single pilot and require a range of 3,000 nautical miles. It would carry a camera capable of resolving objects as small as an individual person. To ensure survivability against Soviet surface-to-air missiles, the airplane would need to attain altitudes above 70,000 feet. Such a platform, he suggested, could provide locations of military and industrial installations, allow for a more accurate assessment of the Soviet order of battle, and allow estimates of Soviet ability to produce and deliver nuclear weapons. Land recognized that the airplanes apparent invulnerability was limited. The opportunity for safe overflight may last only a few years, he wrote, because the Russians will develop radars and interceptors or guided missile defenses for the 70,000-foot region.

Designed as a stopgap measure to provide overhead reconnaissance capability during the early years of the Cold War, the versatile U-2 has since evolved to meet changing requirements well into the 21st century. Though many authors have documented the airplanes operational history, few have made more than a cursory examination of its technical aspects or its role as a NASA research platform. This volume includes an overview of the origin and development of the Lockheed U-2 family of aircraft with early National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) involvement, construction and materials challenges faced by designers and builders, releasable performance characteristics and capabilities, use of U-2 and ER-2 airplanes as research platforms, and technical and programmatic lessons learned.

accessed January 15, 2013.

.Winston Churchill, Maxims and Reflections (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1949), p. 55.

, accessed January 23, 2013.

Chapter 1

Designing for High Flight

Air Force officials had been pursuing the idea of high-altitude reconnaissance since January 1953, when Bill Lamar and engine specialist Maj. John Seaberg of the Wright Air Development Center (WADC) in Ohio drafted a request for a design study to develop a highly specialized aircraft that would be produced in small numbers. Surprisingly, they recommended bypassing such prominent aircraft manufacturers as Lockheed, Boeing, and Convair and instead focusing on Bell Aircraft Corporation and Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation. Their superiors at Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) headquarters agreed that because a relatively small production run was envisioned, these smaller companies would likely give the project a higher priority. In order to provide an interim, near-term option, they also asked officials at the Martin Company to study the possibility of modifying the manufacturers B-57 light jet bomber with a longer wingspan and improved engines. The three companies were asked to submit results by the end of the year. The study project, dubbed Bald Eagle, called for a subsonic aircraft with an operational radius of 1,500 nautical miles that would be capable of attaining an altitude of 70,000 feet and carrying a single crewmember and a payload of between 100 and 700 pounds. It was to be equipped with available production engines (modified, if necessary) and have as low a gross weight as possible.