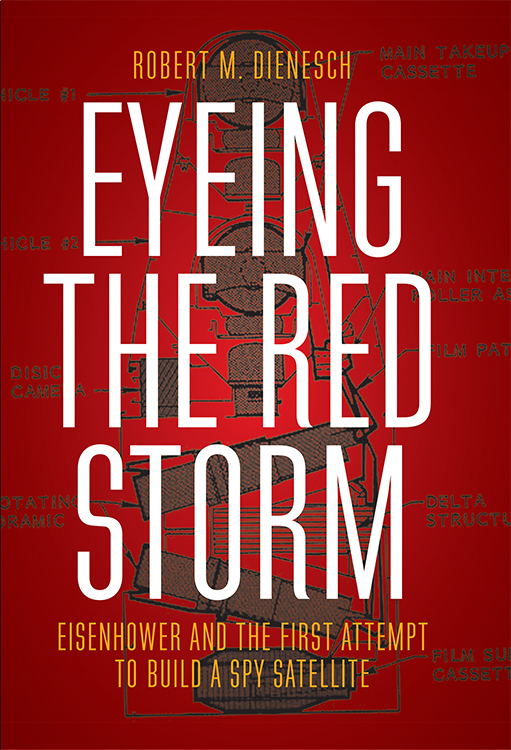

In his well-researched and convincingly argued book, Robert Dienesch has demonstrated clearly that the American spy satellite program, rather than being a knee-jerk reaction to the launching of Sputnik by the Soviet Union in 1957, was instead the culmination of years of effort by the Truman and Eisenhower administrations.

Galen Perras, associate professor of history at the University of Ottawa and author of Franklin Roosevelt and the Origins of the Canadian-American Security Alliance, 19331945: Necessary but Not Necessary Enough

Dienesch combines an explication of high-level policy formulation with technical details about reconnaissance satellite development. He penetrates the secrecy that surrounded Americas first military satellite program, WS -117 L , to assess both its contributions and disappointments.

Rick W. Sturdevant, deputy director of history, Air Force Space Command

Eyeing the Red Storm

Eisenhower and the First Attempt to Build a Spy Satellite

Robert M. Dienesch

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln & London

2016 by Robert M. Dienesch

Cover design by the University of Nebraska Press

Author photo courtesy of Jennifer Mattinson

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dienesch, Robert M.

Eyeing the red storm: Eisenhower and the first attempt to build a spy satellite / Robert M. Dienesch.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-5572-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8675-7 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8676-4 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8677-1 (pdf)

1. Space surveillanceUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. Artificial satellitesUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. Astronautics, MilitaryUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Military surveillanceUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 18901969. 6. Cold WarHistory. I. Title. II. Title: Eisenhower and the first attempt to build a spy satellite.

UG 1523. D 54 2016

358'.88dc23

2015028635

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

I dedicate this book to four people who have meant the world to me.

It is dedicated to the memory of my grandparents: Michael and Susanna Dienesch and Christa Laudenbach; unfortunately they did not live to see the completion of this work. I never knew if they really understood what I was working on; I do know that they loved me and that my world is a little less without them.

The fourth person is my wife, Jennifer Mattinson. Before you came into my life, I was lost and without direction. You have brought back the light and magic in my life. I dedicate this book to you, my cheering squad, my rock, my love.

Contents

Inevitably during the research and writing of a work such as this, a large number of people have given me assistance. It is impossible to give credit to each of them in turn, so I beg their forgiveness for not including a detailed list. However, certain individuals and organizations do stand out for special thanks.

As with every research project a great deal of archive work is essential. I have been lucky that the archival staff I worked with were exceptional. The knowledge of the archivists at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Archive in Abilene, Kansas, and their willingness to assist made my time there not just productive but a splendid experience. I look forward to having the opportunity to work with them again. My thanks to the archivists at both the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, and the George Washington University Space Policy Institute Archives. Both staffs were extremely helpful and effective.

I also want to thank the staff at the journal Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly. Excerpts of my argument on Eisenhowers domestic perspective and his role in the creation of WS -117 L were published in their special issue on the fiftieth anniversary of satellite reconnaissance (volume 17, number 3) in 2010. They took a chance on an unknown historian from Canada, and it has been deeply appreciated.

Dr. Marc Milner, thank you for being a good friend and confidant over the years, listening when I needed to talk and giving me lots of encouragement. Dr. David Charters, thank you for taking on the role of thesis advisor and supervising me throughout my research.

Nicholas, Rob, Jeff, Andre, Dave, and the entire circle of friends who have journeyed with me on this project, you kept me sane and on an even keel, gave me useful advice, and kept me laughing. Thanks, guys.

Of course, my family: you deserve a great deal of credit for all of this. Supporting me when I was ready to give up, keeping me on course and working steadily, you have all earned a portion of the credit for this volume.

Finally, one other person stands out. Dwayne Day, you are a scholar and a gentleman. When my research looked about to founder because of a lack of material in the National Archives, you opened up a whole new set of doors for me, which included your own personal document collection. Considering we had only talked on the phone, that was an incredibly generous gesture. I can only pray that I will be able to repeat the favor for another grad student in the future.

Filling in the Gap

When Americans went to bed on October 3, 1957, little did they realize that the night sky was about to change forever. The only forewarning was a small article in the New York Times, Soviet Expert Tells West of Test of Rocket. Found at the bottom left corner of the first page on the morning of October 4, the piece would have garnered only passing interest had it not been for the events of the day.

At Tyuratam in Kazakhstan, just minutes before midnight on October 4, a Soviet rocket blasted off. At its top sat the Soviet Unions contribution to the satellite program of the International Geophysical Year ( IGY ). Weighing only eighty-four kilograms, the polished metal sphere of Sputnik, meaning traveler, was an oversized radio beacon. Its sole purpose was to orbit the earth and make electronic noise. And what a noise it made! It permanently altered the tranquil night sky. The earth and the moon were no longer alone. A man-made signal pierced the eerie silence of space.

Americans did not immediately grasp what had happened. Traveling at over seventeen thousand miles an hour, the satellite (complete with its booster and protective shroud following in its wake) flew over the United States twice before the U.S. government became aware of it. Radio Moscow first broke the news to the world, playing up the achievement for its propaganda value. In the United States the shock and disbelief were evident. Believing strongly that the nation had to act and that the Americans IGY counterpart to Sputnik VANGUARD would not provide results in the near future, Werner Von Braun, long a vigorous advocate of satellite research and director of the Development Operations Division of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency ( ABMA ), felt that all he needed was the opportunity to launch a satellite. He saw the Soviet success as a challenge that the United States had to meet immediately.

Most of the rest of the country reacted with shock and fear. The event shook Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson ( D - TX ), who quickly realized its political implications. Following dinner on the evening of the 4th, he led guests at his Texas ranch outside to stare at the dark sky, which was no longer reassuring but now created a sense of dread. The consequences for U.S. national security were very clear. If the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) could put a satellite in orbit, the same rocket booster could theoretically deliver a nuclear warhead to an American city. That prospect held enormous potential as a means of challenging Dwight D. Eisenhowers Republican administration (195361).