This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473531604

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

BBC Books, an imprint of Ebury Publishing,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

BBC Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright BBC Books 2019

Cover Design by Two Associates

Cover: 2018, Deimos Imaging SLU, an UrtheCast Company

This book is published to accompany the television series entitled Earth from Space, first broadcast on BBC One in 2018.

Commissioning Editor: Cr aig Hunter

Executive Producer: Jo Shinner

Series Producer: Chlo Sarosh

Series Director: Barny Revill

Producer/Director: Justin Anderson

Producer/Director: Paul Thompson

Edit Producer: Hannah Gibson

Additional directing: Katie Parsons, Patrick Evans, Natasha Filer and Bertie Allison

First published by BBC Books in 2019

www.eburypublishing.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781785943539

Commissioning Editor: Albert DePetrillo

Project Editor: Bethany Wright

Picture Research: Laura Barwick

Image grading: Stephen Johnson,

www.copyrightimage.co.uk

Design: Bobby Birchall, Bobby&Co

Introduction

Observing the Earth: a short history

During the Late Stone Age, about 27,000 years ago, a group of hunter-gatherers in the Pavlov Hills, in what is now the Czech Republic, looked around the landscape in which they lived and realised that if they had some means by which they could easily find their favourite hunting grounds and the best places in which to camp, then they would have a better chance to survive. Word of mouth from one generation to the next would have been one way to stoke tribal knowledge, but these people had a new and more permanent solution: they scratched marks onto a mammoth tusk, and this would provide them with a visual representation of where they had been, where they were now, and where they could go in other words, they had created a map.

Those early cartographers were limited in their outlook. They had to make their observations from the tops of hills or, like later civilisations, from the masts of ships, but that did not stop them from considering the bigger picture. There was always a desire to view ourselves as the gods might see us, and in the sixth century BCE , the Babylonians had a go at depicting the entire Earth in space with their Map of the World. It is a clay tablet, in size about 12 by 8 centimetres, that shows our planet as a flat disc surrounded by the sea, and, according to the British Museum where the artefact is kept, it is thought to be copied from an earlier depiction made sometime after the ninth century BCE .

Archaeological finds like these show how, since the mists of time, people have had an abiding curiosity about what the world looks like when seen from above. But it was not until Greek philosophers and mathematicians came along that we realised the Earth was not a flat disc, but a sphere. It was the perfect shape the gods would have preferred.

By the 13th century CE , ancient mariners had drawn up navigational charts, like the portolan charts, which guided ships across the world in pursuit of silk, spices, opium, political influence and the conquest of new lands. They were so valuable that the charts were often closely guarded state secrets, and the outlines of the known continents were remarkably accurate considering the highest a ships navigator could climb to view the sea and shore was to the crows nest, about 30 metres above the deck.

Then, during the 18th century, there was a quantum leap in the way the Earth could be observed: the invention of the balloon. In November 1783, the Montgolfier brothers flew a manned balloon in France, but it was not until 75 years later that balloons were used to take photographs of the Earth below.

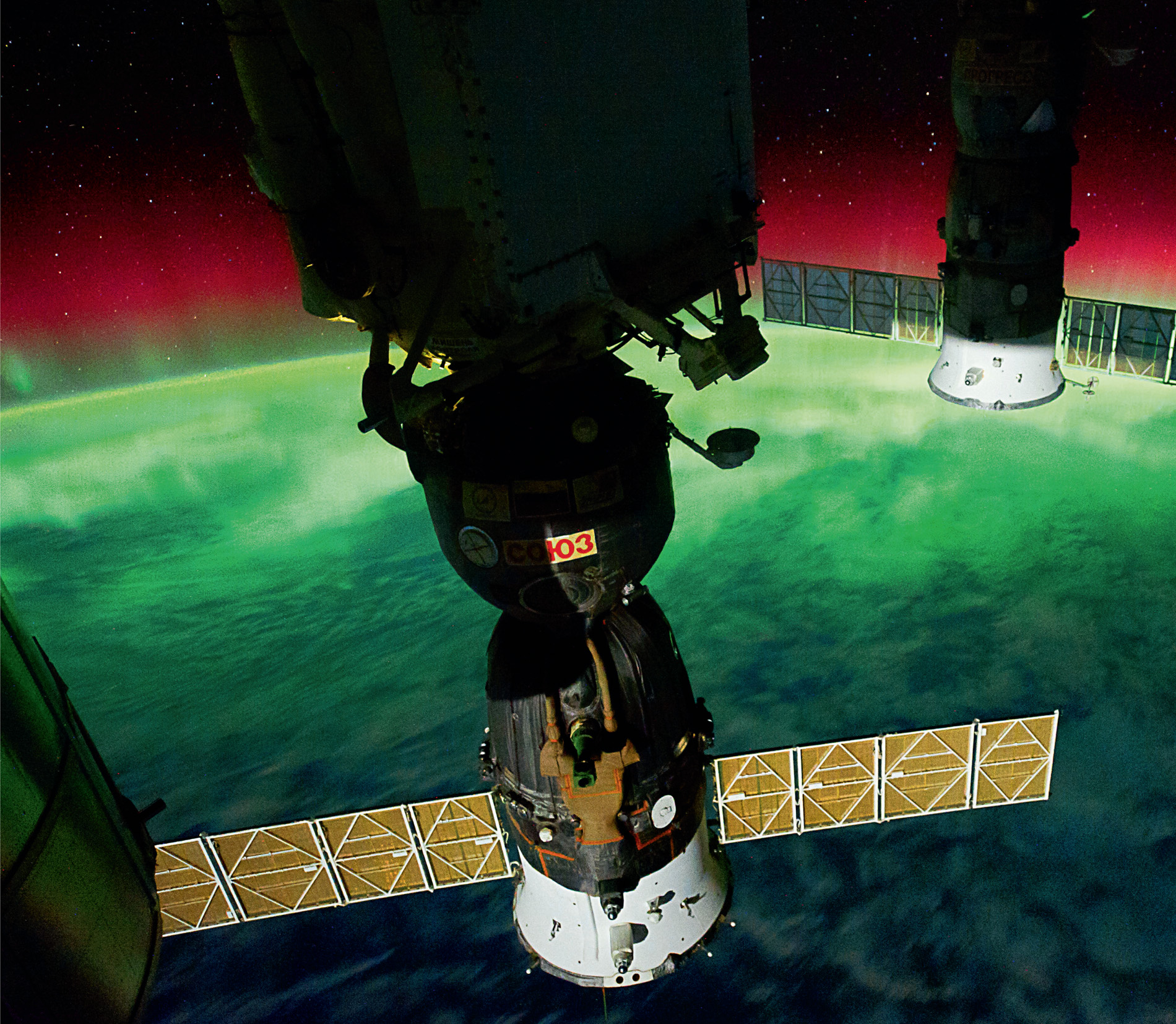

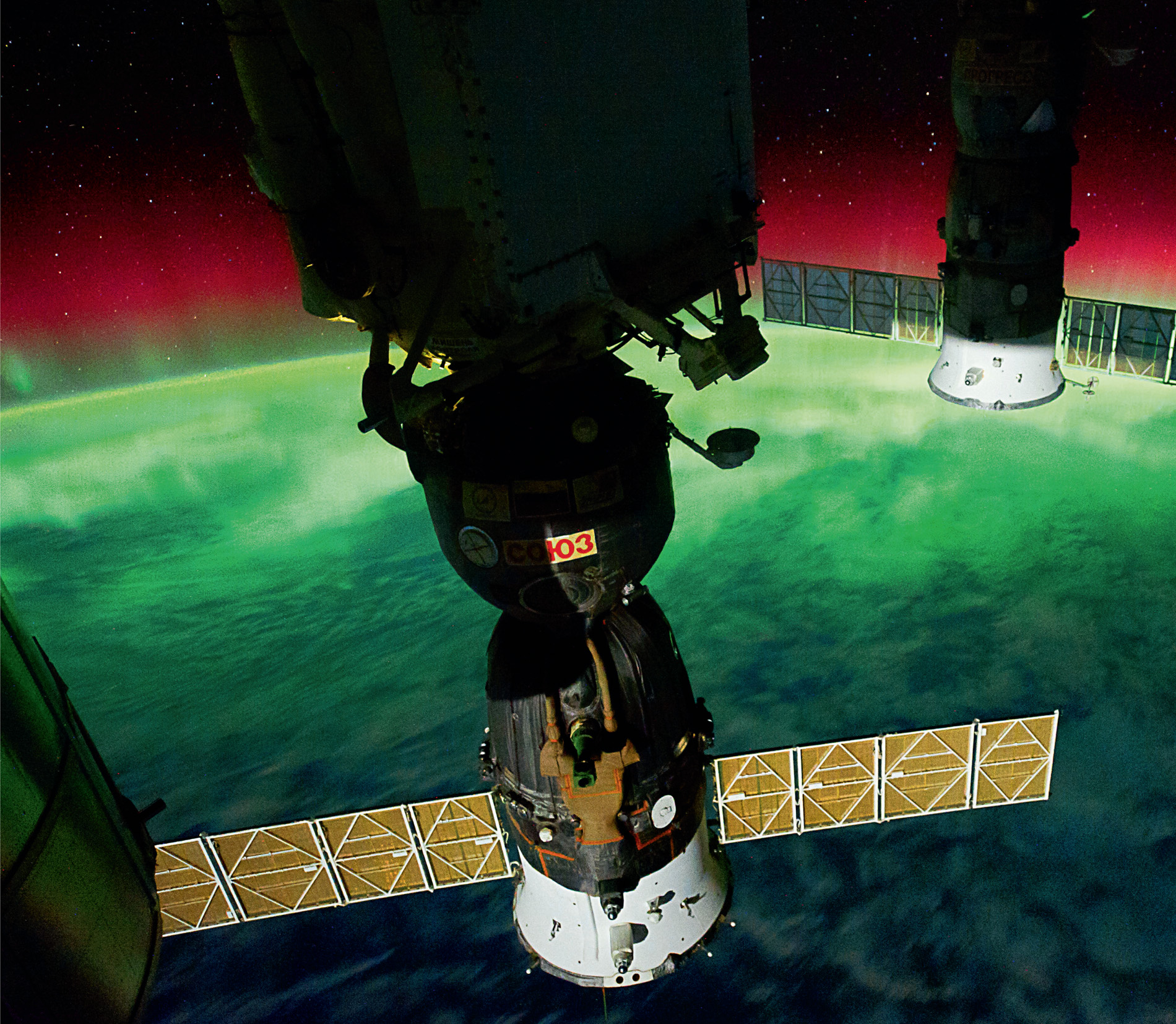

It has taken less than 25,000 years to get from a simple map scratched on a mammoths tusk to an International Space Station from which pictures can be taken of an aurora from above. Our ancient forebears were eager to see our world as the gods saw it, and now we can do just that. Astronauts dreamed of travelling to other worlds, but it wasnt until they looked back and saw our delicate planet hanging in the void of space that we came to have a new kind of self-awareness, something that an International Space Station crewman described as orbital awareness a new and holistic view of the world. Image courtesy of NASA Johnson Space Center.

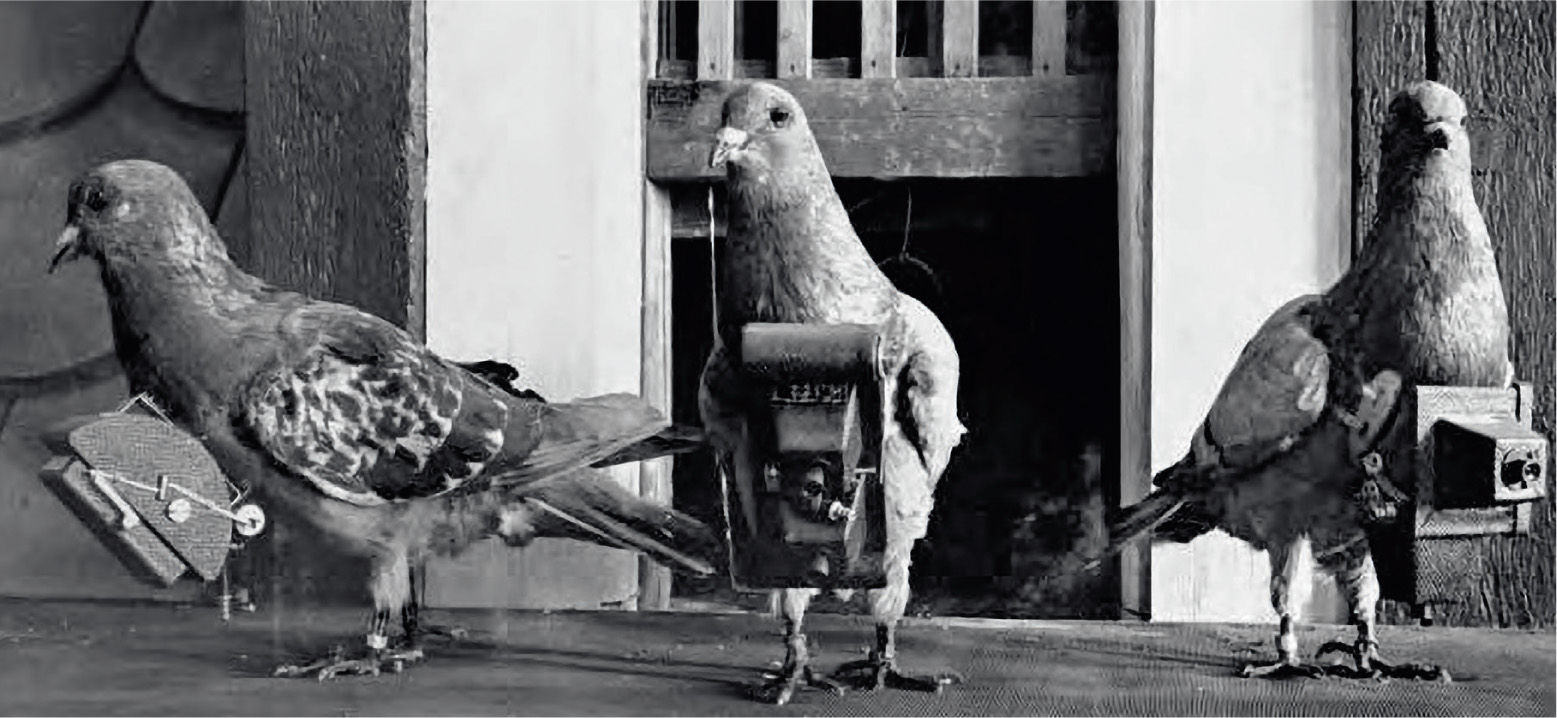

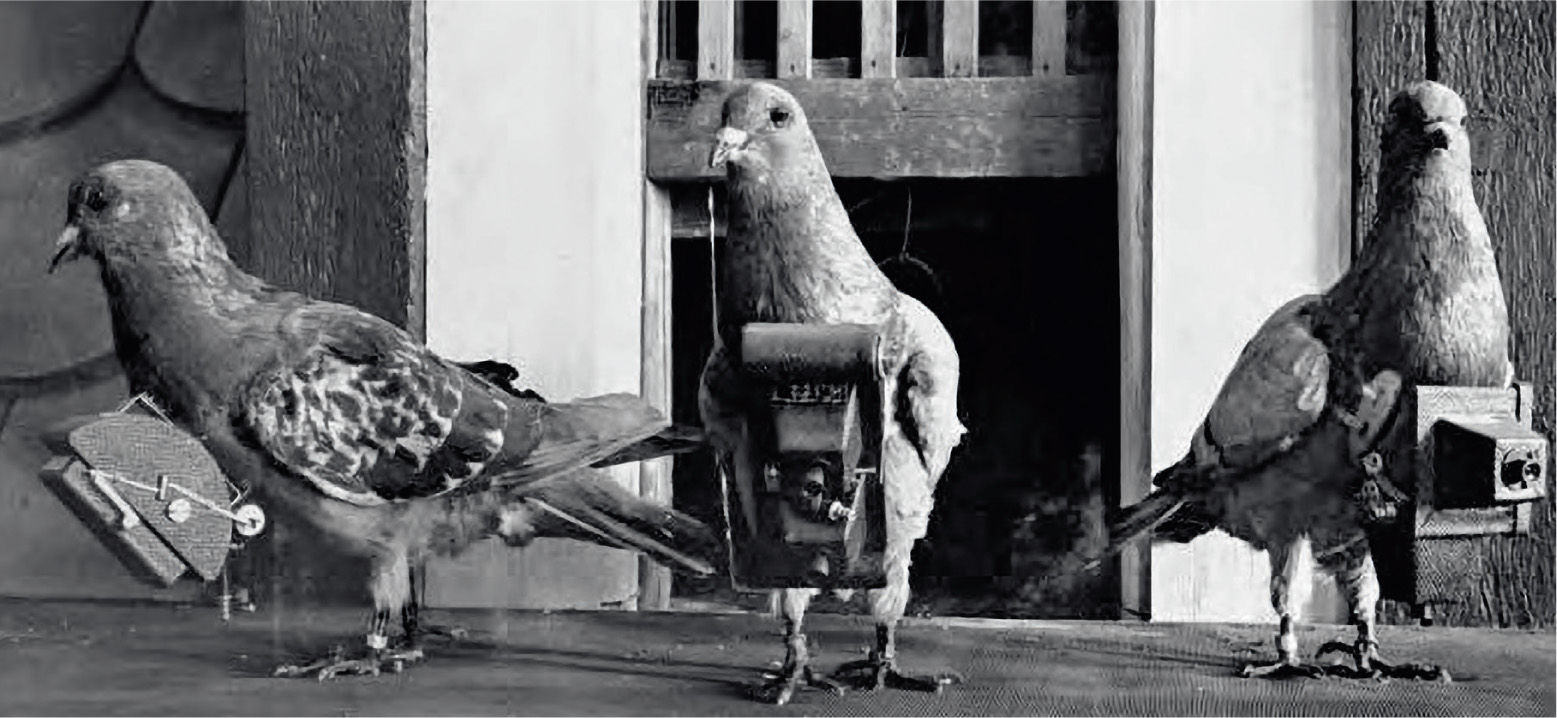

Pigeons were in the vanguard of the first Earth photographers. Julius Neubronners pigeons carried cameras into international expositions in several European cities in the early 1910s. Pictures they had taken on their flight were developed, printed and sold as postcards.

The pioneer was French photographer Gaspard-Flix Tournachon, known professionally as Nadar. In 1858, he took the first known aerial photograph from a tethered balloon about 80 metres above the valley of the Bivre. It was not easy. The wet colloidal photographic process in those days involved him taking not only a bulky camera and tripod, but also an entire darkroom in the balloons basket. These early balloonists took enormous risks and very often put their lives in danger.

In the USA in 1860, American photographer James Wallace Black and his fellow balloonist Samuel Archer King tried to photograph the countryside around Boston, but their balloon broke free and they were dumped unceremoniously but safely in high bushes about 50 kilometres from their starting point. Two years later, British scientist James Glaisher and balloonist Henry Tracey Coxwell attempted to go considerably higher in order to photograph above the clouds. They reached an altitude of about 10,900 metres, but Glaisher passed out due to a lack of oxygen. Coxwell lost all sensation in his hands, but could pull the relevant valve cord with his teeth, and they returned gently to the ground but failed to photograph anything at all. And, in the early 1900s, George R. Lawrence was photographing from a cage strung beneath a balloon above Chicago when the cage detached itself and both Lawrence and camera fell towards the ground, only to be caught by telephone wires. Miraculously, he walked away unharmed.

During the years that followed, the desire to photograph the Earth from above gave rise to techniques that became increasingly bizarre. In 1903, German apothecary Julius Neubronner designed and patented a small camera mounted on the breast of a pigeon. The pigeon did not always fly the intended track, but creating a camera this small was an achievement nonetheless. The pigeons were probably less impressed, flying as they did with a wooden box attached to their breast. It was a wonder that they were able to take off at all, let alone fly!

Next page

It has taken less than 25,000 years to get from a simple map scratched on a mammoths tusk to an International Space Station from which pictures can be taken of an aurora from above. Our ancient forebears were eager to see our world as the gods saw it, and now we can do just that. Astronauts dreamed of travelling to other worlds, but it wasnt until they looked back and saw our delicate planet hanging in the void of space that we came to have a new kind of self-awareness, something that an International Space Station crewman described as orbital awareness a new and holistic view of the world. Image courtesy of NASA Johnson Space Center.

It has taken less than 25,000 years to get from a simple map scratched on a mammoths tusk to an International Space Station from which pictures can be taken of an aurora from above. Our ancient forebears were eager to see our world as the gods saw it, and now we can do just that. Astronauts dreamed of travelling to other worlds, but it wasnt until they looked back and saw our delicate planet hanging in the void of space that we came to have a new kind of self-awareness, something that an International Space Station crewman described as orbital awareness a new and holistic view of the world. Image courtesy of NASA Johnson Space Center.  Pigeons were in the vanguard of the first Earth photographers. Julius Neubronners pigeons carried cameras into international expositions in several European cities in the early 1910s. Pictures they had taken on their flight were developed, printed and sold as postcards.

Pigeons were in the vanguard of the first Earth photographers. Julius Neubronners pigeons carried cameras into international expositions in several European cities in the early 1910s. Pictures they had taken on their flight were developed, printed and sold as postcards.