VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (Australia) 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada) 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Canada ON M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ) 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Penguin Group (Australia), 2012

Text copyright Robin de Crespigny 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

penguin.com.au

ISBN: 978-1-74253-435-0

ROBIN DE CRESPIGNY

The People Smuggler

THE TRUE STORY OF

ALI AL JENABI,

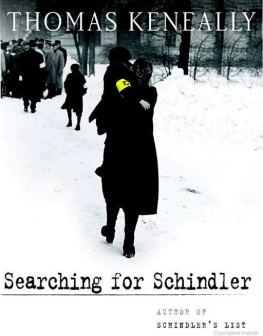

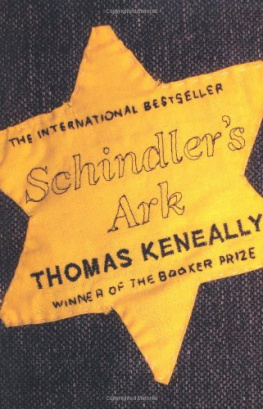

THE OSKAR SCHINDLER OF ASIA

VIKING

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

For Ahmad.

And for my sister Paddy,

who died during the writing of this book.

Authors Note

I began the long journey of writing this book when refugee advocate Ngareta Rossell came to me in 2008 with the idea of writing a film script based on the life of Ali Al Jenabi. The epic breadth of his story is so great, with its cast of thousands, military conflicts, desperate mountain treks, boats on highs seas, and a journey across two continents and at least six countries, each with its own unique culture and language, that I somewhat gratefully took the suggestion of screenwriter John Collee to tell the story in book form first.

Thus began an expedition of more than three years working intensely with Ali. He is an Arabic Muslim man and I am a Western agnostic woman. Gaining each others trust, especially after what he had been through, meant that initially we focused on the events and not the internal story. What fascinated me most was not only Alis moral fibre and strength of spirit, but the depth of his self-awareness. This was accompanied by an infectious sense of humour that seemed to transcend even the most severely traumatic incidents. In truth, despite Alis remarkable memory, it was tremendously hard for him to dredge up the details of his life for months on end.

We met every few weeks, often over lunch at Ngaretas home. I recorded all our conversations, then spent long hours meticulously transcribing them. By the time I had mapped out the complex sequence of events in his story we had grown to know each other better, so returning to the start I asked more personal questions, and bit by bit we traversed the emotional depths of his odyssey. For me the meat of the story is the life-changing moral choices he faced while carrying so much responsibility for others, and the internal process by which he made his decisions.

As we went deeper I found the emotions involved were ones we can all identify and empathise with. In this way I believe it is a universal story about one individual in the storm of life, and that by travelling with him we can understand the bigger picture of why people make the choices they do to get on leaky boats, and how none of it is black and white. This is a story not so much about people smuggling, as about a man who happened to become one.

Half a lifetime of extraordinary events with hundreds of encounters has demanded some truncation of incidents and merging of minor characters. Also some names have been changed or omitted. This is particularly notable in the chapter dealing with the hearing in the Darwin Magistrates Court. The Commonwealth DPP refused to agree to co-operate with the lifting of a suppression order on witnesses, despite the relevant details being freely available on the internet.

Like all refugee stories where trauma is a daily fact of life, it has not always been possible to tie down exact dates, and very occasionally I have had to reconstruct incidents with the fragments of memory available, offsetting them where possible against more certain recollections, or lining them up with known historical incidents. However, the tone and emotional experience is always accurate.

I made the decision to write this book in the first person to enable the reader to experience Alis life at first hand by being placed in his shoes. Until Ali reached Australia he spoke Arabic, Kurdish, Farsi and Indonesian, but very little English. So the voice is essentially a construct of him and me, in the English language as he might have used it. As all the events are through his eyes, the view of those events reflect Alis recollections.

I feel privileged that Ali has allowed me to preserve his story and pass it on to the world.

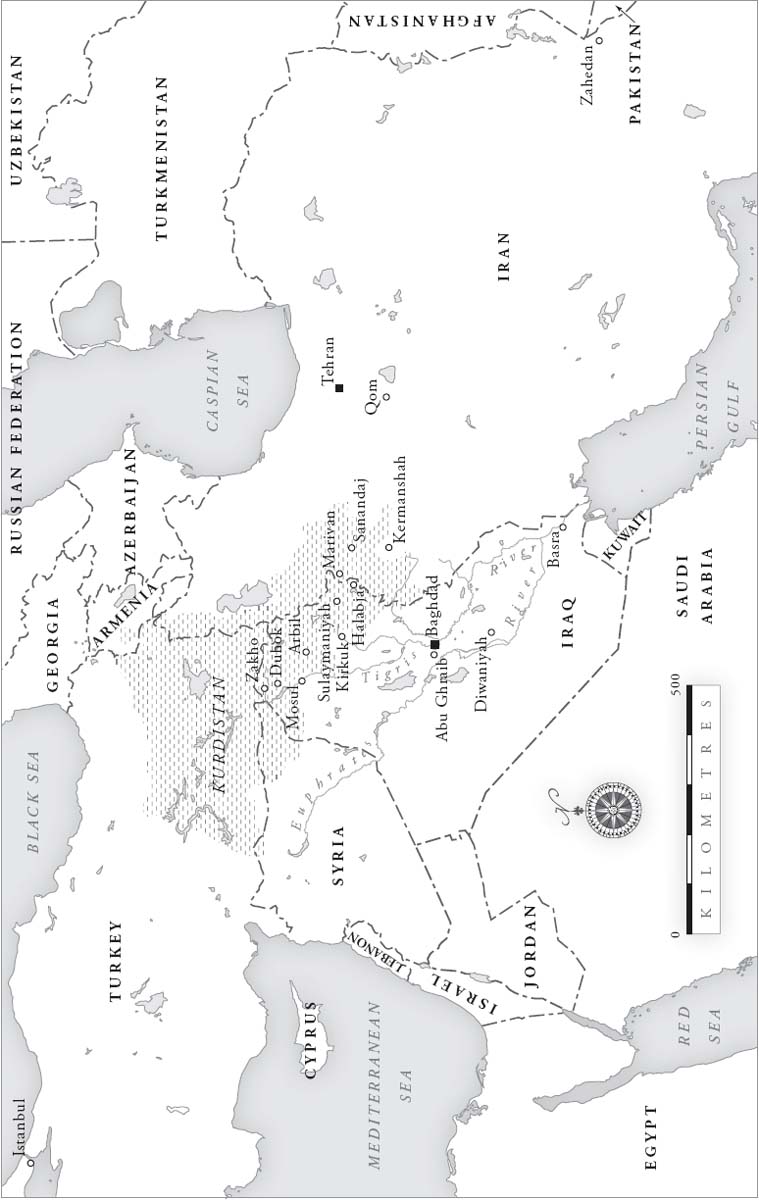

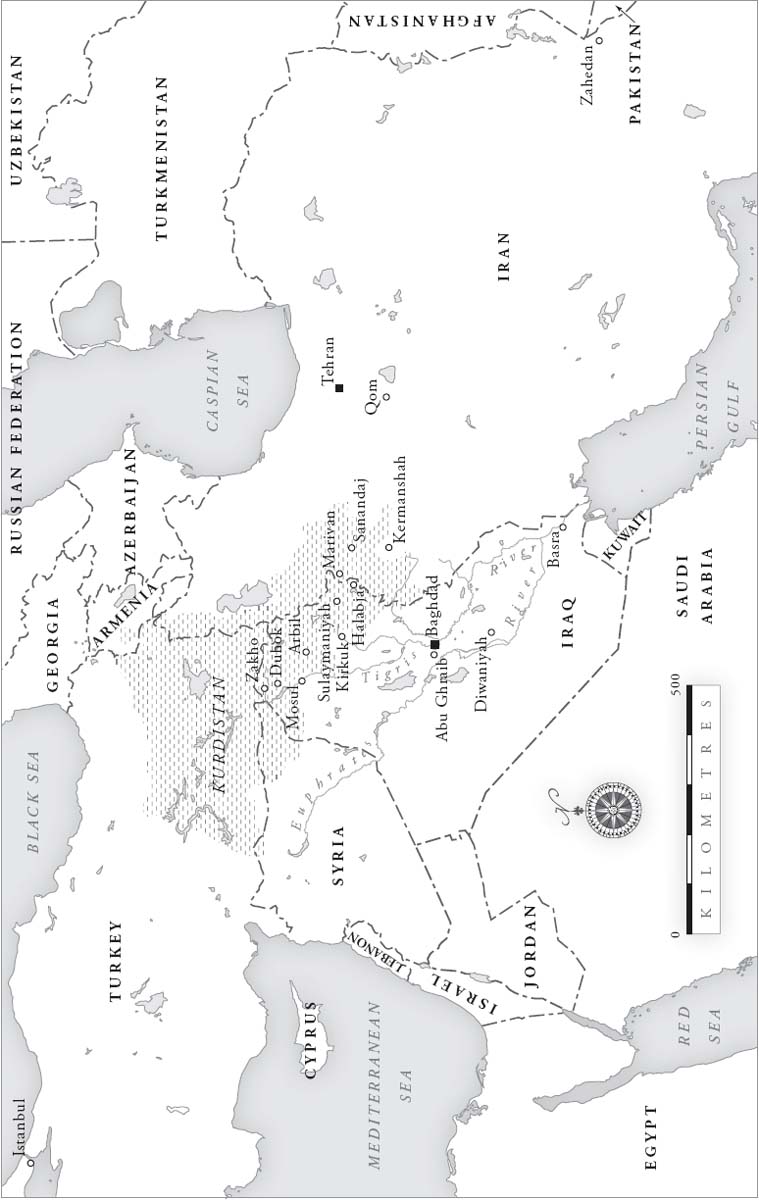

The Middle East

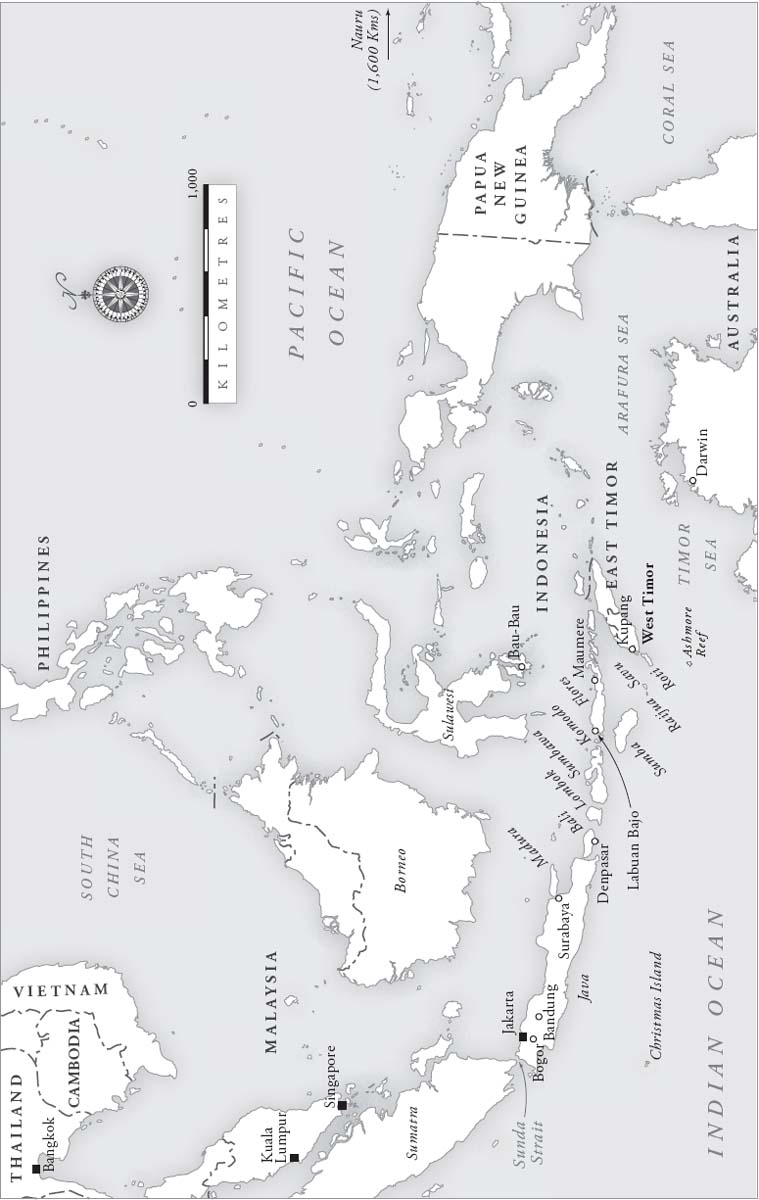

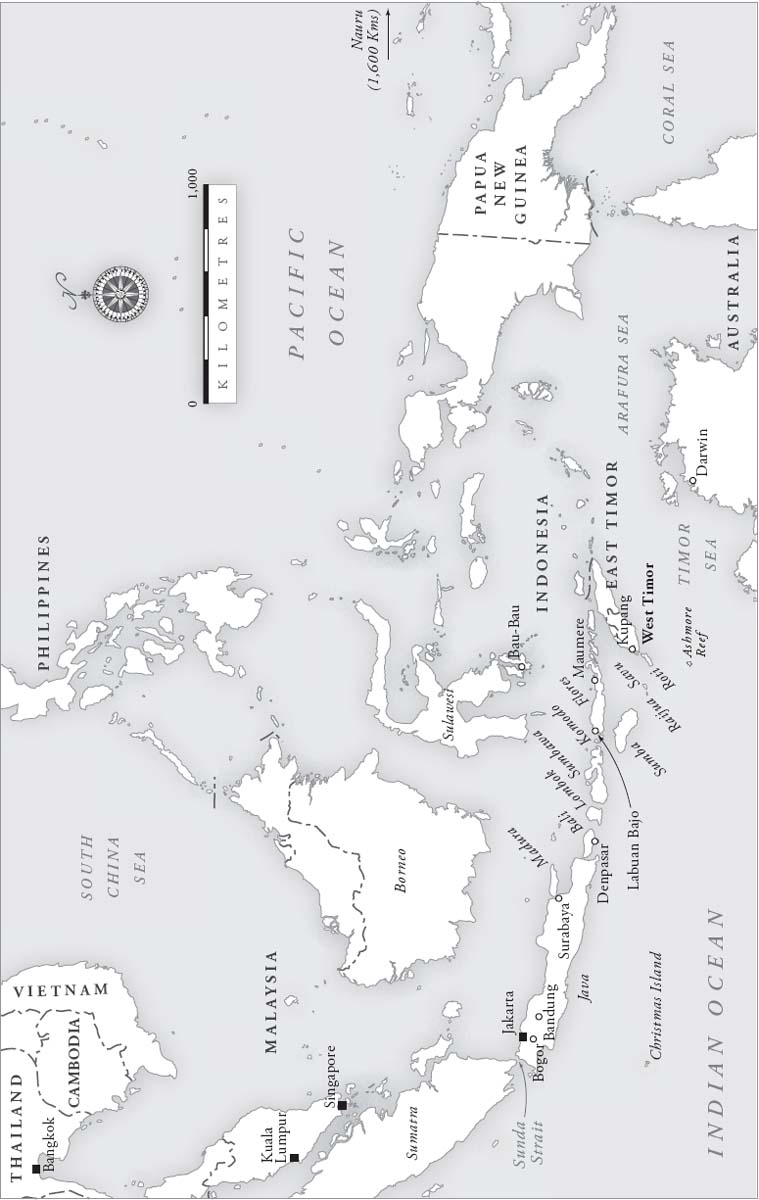

South-East Asia

Hassan Pilot

I am the oldest son, which meant my parents gave me everything. I was lavished with attention, but that was not what inspired my affection for my father. He was a man with an indomitable spirit. Once a proud and dignified man. Once the centre of my universe. He was full of fire yet tender, outraged but calm. For the first ten years of my life I loved everything about him.

It seemed to my young eyes that he was made of steel, yet every morning when I was little he would walk me to school. I would patter alongside gazing up at his towering figure. Once there, he would let go my hand and put a dinar in it. Just in case, he would say.

I would wrap my tiny fingers around it with a sense of growing independence, which he would then destroy by asking for a kiss. As he watched me go, I loved the feel of his eyes on my back. I knew he was proud of me, but he would never say it, he wanted me to be tough.

My father had a reputation as an individual, he was the son of the Pilot. Not that the Pilot flew planes, on the contrary, but one night when my grandfather was particularly drunk he stood on the roof and said, They think I cant fly. I fly! And he jumped off and broke half the bones in his body.

It became a story amongst the people of our city who named my grandfather Pilot, so my father, Hassan, became known as Hassan Pilot.

My grandfather walked with difficulty on two crutches for the rest of his life, but like my father in those early years he remained jovial and good-humoured. When he was on his deathbed Hassan Pilot took me to see the dying Pilot, but I was only six and was confused by his sickly smell, and the sucking in and out of breath, and I ran from the room. I did not yet know about death.

When I was a little older my four brothers and I would wait in the afternoon for my fathers return from his shop, where he made windows and doors to keep our family in the middle-class comfort my mother was accustomed to. We would sit in the house guessing if those were his footsteps, or if that was his voice singing, as he so often did. And then the door would fly open and we would all leap on him.