Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2020

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Sanjiv Sachar and Madhavi Sachar 2020

Photographs courtesy: Sanjiv Sachar and Madhavi Sachar

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-93-90356-67-6

First impression 2020

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

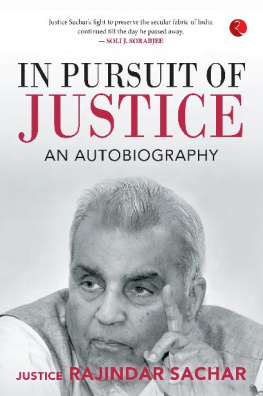

FOREWORD

Soli J. Sorabjee

It is impossible to describe the many splendored qualities of Justice Rajindar Sachar. Born in Lahore in 1923, son of Bhimsen Sachar, a prominent Congressman and Gandhian and Chief Minister of Punjab post 1947, Justice Rajindar Sachar was a socialist, an egalitarian, a staunch defender of civil liberties, and, above all, a humanist.

He witnessed the pain and fangs of Partition. Yet, creditably, he never bore any animosity towards Pakistan or its people.

Sachar was appointed a judge of the Delhi High Court in 1970 but was transferred out of Delhi High Court for voicing his opposition to the spurious 1975 Emergency. He was brought back to Delhi High Court after Emergency was revoked. Thereafter, he rose to become the Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court. It was a pleasure to appear before him and assist him in delivering judgments which upheld the fundamental rights of Indias citizens.

After retirement, Sachar headed the Peoples Union for Civil Liberties for many years. The reason Justice Rajindar Sachar is most remembered is the Sachar Committee report (2006) which documented the social and economic condition of Muslims in India. The Report evoked both praise and criticism, with some irrational elements advocating that he be sent to Pakistan.

However, his fight to preserve the secular fabric of India continued till the day he passed away. It is heartening that Sachars autobiography comes at a crucial time when Indias democracy is under strain from within.

Chapter 1

MY FORMATIVE YEARS

O ne of my earliest childhood memories is of seeing my father, Bhim Sen Sachar, being arrested in 1930. He was a staunch follower of Mahatma Gandhi. It was a time when the freedom struggle had touched a new high with the mantra of civil disobedience, energizing Indians across the country to defy the British government. I was six years old then. I didnt burst into tears or cry out as Father was being taken away. His arrest did not strike me as something terrible. On the contrary, I was proud of him. My mother and I went to the Gujranwala Jail (in present-day Pakistan) to see him before he was shifted to the Lahore Central Jail.

My father was practising as a lawyer in Gujranwala then. I, however, was born in Lahore as per the Hindu custom of the first child being delivered in the mothers parental home. I was born on 22 December 1923 in the house of my maternal grandfather, Rai Bahadur Mukund Lal Puri, a leading lawyer of the Punjab High Court. My mother, Lalita, had been the only child for twelve long years and my grandfather was very fond of her.

My paternal grandfather, or Babuji as we called him, Nanak Chand Sachar, was in government service in Peshawar and retired as additional assistant commissioner. He was conferred the title of Rai Sahib by the British government. During his years in service, he had become increasingly religious, so when he was offered an extension, he refused it. Although he had led a comfortable life and wanted the same for his children, he had developed a broad concept of renunciation. For that reason, when he was offered land in the new canal colonies of Montgomery, Sargodha (in the erstwhile West Pakistan), he refused. (Incidentally, some of the wealthiest landlords in Punjab were those who had been given these lands for development by the British, as was the usual practice). Grandfathers ancestral house was in Wazirabad in Gujranwala district, in a locality called Mohalla Sacharan (neighbourhood of Sachars).

My father, the second oldest among five children, was born in Peshawar on 1 December 1893. He received his school education in various places, attending the Dayanand Anglo-Vedic (DAV) schools in Lahore, Peshawar, Wazirabad and Quetta (Balochistan), where his brother, older than him by twelve years, had a government job. He graduated from DAV College, Lahore, and joined a law college.

In 1918, Father started his legal practice in Gujranwala. He used to dress like a dandy in those days, with his English suits and stiff collarsthe usual attire of an English gentleman. All that changed when he joined the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1920, in response to Gandhijis call for non-cooperation. Father consigned his Western clothes to the bonfire and took to the Indian achkan and churidar, which he wore throughout his life. Though he had enjoyed eating meat, he gave it up in 1921, abstaining from it for the rest of his life. But he was not dogmatic about it. When I was a child, meat was cooked daily at home as my mother was a meat eater. Not only that, it was cooked in the same kitchen where the vegetarian food was prepared.

When Father joined the INC, Lala Lajpat Rai, the pre-eminent Congress leader of Punjab province, sent him to his best-loved district Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) as a Congress organizer. Suspending his legal practice, he stayed there till June 1921. Thereafter, he returned to Lahore and took on the role of registrar at the newly established National College.

At that time, the Non-cooperation Movement, launched by the Congress under the leadership of Gandhiji, was in full swing. Following the arrest of Lalaji as well as the Congressmen who took charge of the movement after him, Father assumed the reins of the Satyagraha Movement in Punjab. But before he could commence his work, Gandhiji called off the Non-cooperation Movement in the wake of the Chauri Chaura incident in February 1922 when a mob killed policemen and civilians and burnt the police post at Chauri Chaura (in present-day Uttar Pradesh).

Gandhijis decision drew adverse reactions from several Congressmen, including an explosive response from Lala Lajpat Rai. When Father went to see Lalaji in jail, [] he thrust a bunch of papers into Bhim Sens hands and said angrily, Take it to Gandhi. He has ruined us, destroyed us. The letter was dynamite, which only Lalaji could write to Gandhiji because of his stature and closeness to the Mahatma. Around that time, Father was offered the post of secretary of the Gujranwala municipal committee. He was backed by both rival groups, one led by a Hindu and the other by a Muslim. After demonstrating his administrative abilities for a couple of years, he resigned from the post in 1924 and resumed his legal practice. However, he remained an elected member of the municipality for several more years.