BARBRA STREISAND

BARBRA STREISAND

Redefining Beauty, Femininity, and Power

NEAL GABLER

Copyright 2016 by Neal Gabler.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (US office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (UK office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

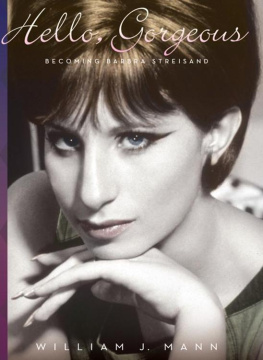

frontispiece: Photo by Lawrence Schiller. Polaris Communications, Inc.,

All Rights Reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015957531

ISBN 978-0-300-21091-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10987654321

For my beloved daughters, Laurel and Tnne,

and my beloved son-in-law, Braden,

And for all those who have ever been told they could

not succeed

You never quit, do you?

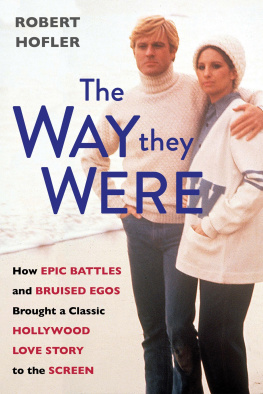

Hubbell Gardner, The Way We Were

CONTENTS

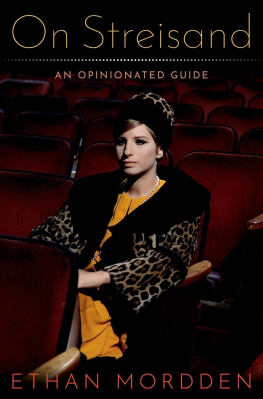

An Introduction: Shaynkeit

IT IS one of the seminal moments in American film and, quite possibly, American culture generally. The camera dollies in toward a woman in a leopard-skin coat and matching hat, her back to the camera, then veers slightly to the left to reveal an ornate, gold-framed, full-length mirror in which we see the womans image, though her face is obscured by the coats collar. She pulls down the collar just enough to reveal that inimitable Streisand visage, arches her brows, and assesses herselfcoolly. Then she purrs, Hello, gorgeous. There is a cut to a close-up, and Streisand emits the tiniest, almost inaudible laugh/snort, as if it were a joke, though she acts as if the joke is on us. It is. But then her expression turns dark, wistful, as if to tell us how far she has had to come to utter those words.

This is how Barbra Streisand introduced herself to the film audience in Funny Girl in 1968, and what an introduction it was! First, there is her looka kind of exoticism, half Afghan hound, half Jewess. And then there is the mannerthe secretiveness, the cool, diva elegance only slightly betrayed by those arched brows, the self-scrutiny that gives way to self-consciousness that gives way to self-confidence that gives way to self-doubt. And then there is the voicethat unmistakable Brooklyn accent, the gorgeous elongated to gaaaaw-jus, an accent that just didnt comport with the regal bearing, the expensive coat, the sense of control. And then there is that laugh, as if to say well, it said a lot. And then that sadness, which said even more.

One of the things it said is that Streisand wasnt making fun of herself or being ironicshe was gorgeouseven though no one who looked like Streisand or had Streisands obvious ethnicity, that double whammy of Judaism and Brooklyn, or had that strange self-regard Streisand had, had ever become an American movie star, certainly not a dramatic star, and Streisand would become the biggest. When Streisand addressed her image in that mirror, she was asserting her beauty and validating a new kind of glamour, a new kind of star, a new kind of power. Hello, gorgeous was Streisands way of ushering in a new era, and just about everybody seemed to recognize it. Although there had never been anyone on movie screens like Streisand, there were millions of Streisands, tens of millions, watching those screens, as Streisand herself had before she became a star. Now they had someone of their ownsomeone whom they didnt have to dream of becoming, which was the general vicarious transaction for movie audiences, but someone they felt they already were. Barbra Streisand had that effect. She wasnt Hollywood. She was Brooklyn. She wasnt them. She was us.

It may seem peculiar to freight an entertainer with that much psychological and cultural weight, but Streisand isnt just an entertainer. She has long been a cultural forcethe kind of personality who inspires effusions, poems (Wayne Koestenbaums Streisand Sings Stravinsky), stage plays (Buyer and Cellar by Jonathan Tolins), art (Four Barbras by Deborah Kass), songs (Barbra Streisand, by Duck Sauce, in which her name is the only lyric), even a viciously hostile South Park episode. After fifty years in our eyes and our ears, she is part of the American consciousness as few entertainers have been.

Obviously none of this would have happened without her enormous talent. She was the most successful, and perhaps talented, performer of her generation, Michael Shnayerson wrote in Vanity Fair. Most music critics regard her as the greatest popular female vocalist, and the only singer to stand comparison to Frank Sinatra. Like Sinatra, she changed the dynamics of American popular singing, and she spawned a generation of imitators. Every time you hear a female vocalist trilling in the highest registers or stretching a vowel or shaping the air with her hands or putting on the Bernhardt, you can rest assured that Streisand was there first.

But talent alone, even talent as abundant as Streisands, doesnt make a cultural icon. It may not even be a prerequisite. What makes an entertainer into a cultural icon is the way in which he or she strums our psychic chords and comes to serve as an embodiment of our own deep impulses. He or she seems not only to understand us but to express us. The lives of such rare entertainers, or at least the lives they express through their work, comprise a theme about us.

Usually this appeal is subtext, a whisper under the performance: Marlon Brandos brooding iconoclasm, Sinatras cool, the Beatles irreverence. In Streisands case, it was all texta shout rather than a whisper. Streisand, whose mother discouraged her from pursuing show business because she felt her daughter was too unattractive to succeed; Streisand, who never even got the solo in her own high school chorus because a classmate sang more operatically; Streisand, who was immediately dismissed when she auditioned for parts because of her looks; Streisand, who seemed to be an afterthought in everything she attemptedStreisand stood for every plain girl who had ever been rejected.

She sang songs of loneliness and despair and longing. People who need people . Whats too painful to remember, we simply choose to forget . You dont bring me flowers anymore . In her plaintive voice, one could hear and feel every slight, every insult, every wound. Tennessee Williams said of that voice that it was pure and sweet but bolstered by so much rage, all of which had been invested in the pursuit of artistic excellence.

And hers was a Jewish American success story, too. Her sense of marginalization in a culture increasingly devoted to homogenization was a Jewish alienation. I am deeply Jewish, she once said, but in a place I dont even know where it is. Indeed, Streisand seemed to understand that it was her look and her flaunting of her Jewishness that made her so distinctive and that connected her to the audience. It has been said of her that she was the first star who succeeded because of her Jewishness and not in spite of it.

Next page