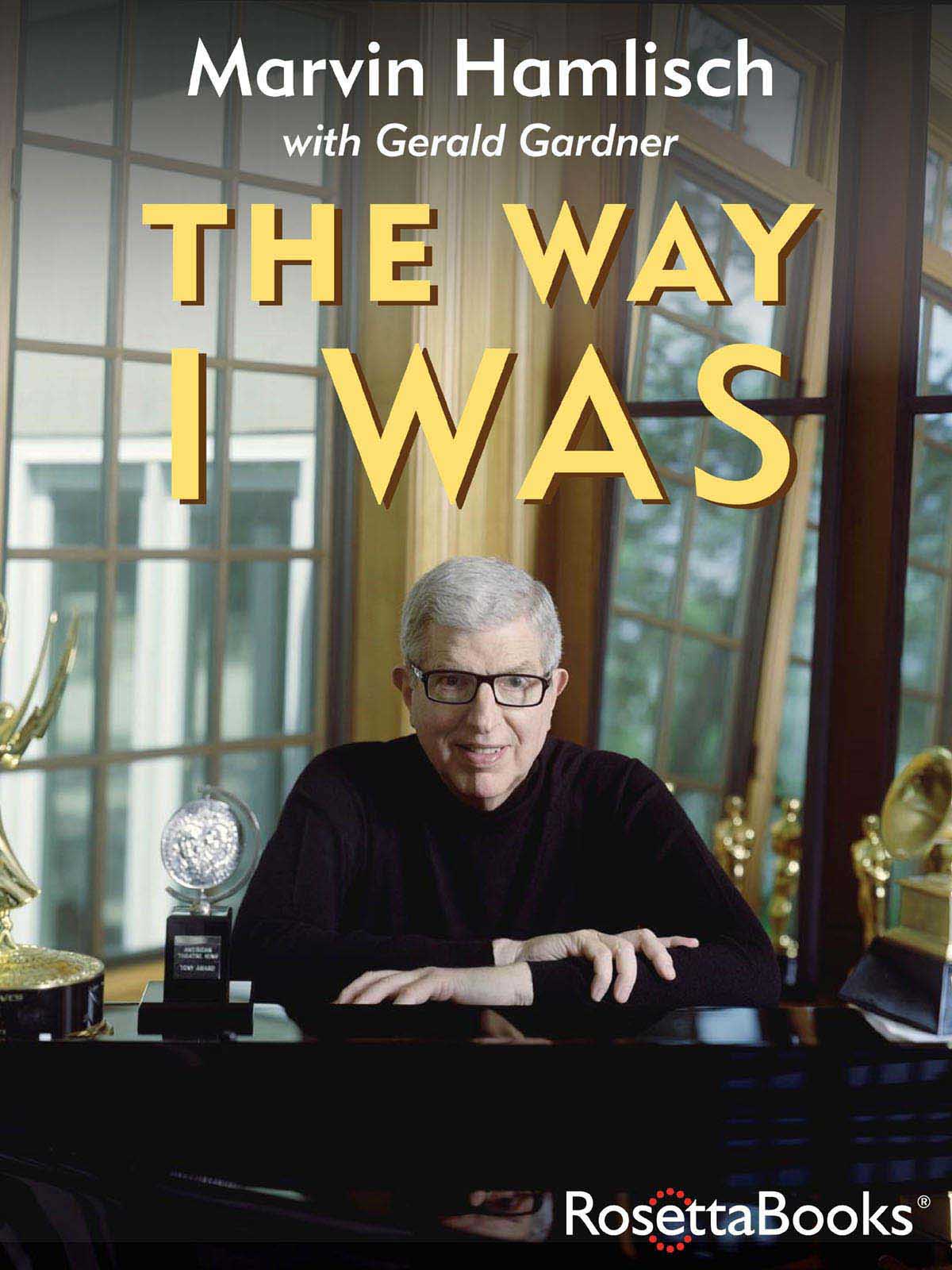

The Way I Was

Marvin Hamlisch

with Gerald Gardner

Copyright

The Way I Was

Copyright 1992, 2013 by Marvin Hamlisch and Gerald Gardner

Cover art to the electronic edition copyright 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover photograph copyright 2012 Len Prince. http://www.lenprincestudio.com/

Electronic edition published 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York.

Cover jacket design by Misha Beletsky

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795333781

To the memory of my beloved parents

To Terre

Contents

A Note from the Author

Picture this. Little Marvin, age six, is ushered into his admissions test for the Juilliard School of Music. There I am, in my Sailor Boys suit, facing three tall men. (Everybody looks tall when youre six.)

A professor asks:

Marvin, will you be playing any Mozart for us? Or possibly Clementi?

No, I said. I dont know who Clementi is. And I never studied Mozart.

Then what will you be playing for us?

Well, I listen to the radio a lot. I can play Goodnight Irene.

The professor pondered.

Well, I dont know Goodnight Irene, he said.

Thats all right, says Little Marvin. I can play it in any key you want.

And so I proceeded to play the song in every key the professor named. And those were the keys that opened the lock to the Juilliard School of Music.

Come to think of it, I dont recall anyone ever asking, Marvin, do you want to take piano lessons? My father, a musician himself, recognized that I had musical talent. By three, I would keep time to the music on the radio in our apartment. By the time I was five, when my sister took her piano lessons, I would listen from the kitchen, and when her teacher left, I would go to the piano and pick out all the songs by ear. Everyone saw in me some sort of wunderkind whose talents had to be served. Given all this, my father felt it his duty to launch me on a career as a great concert pianist. The problem was, that was his dream, not mine.

So from age six to twenty I attended a school where I unfailingly threw up before every final exam. I was terrified that Id betray my fathers hopes. And for fourteen years I competed with a pack of driven young kids who wanted to become the next Horowitz. Me, I wanted to become the next Cole Porter. Unfortunately, there were no classes in this hallowed institution where one could learn how to write a Broadway show; no Berlin 101 or Rodgers 202.

As the Juilliard years dragged by, I concealed my true tastes like a spy behind enemy lines. I lived in fear that my guilty secret would be discovered. No one at Juilliard must know that I loved Jerome Kern and Harold Arlen. By age seven, in our tiny apartment on West Eighty-first Street, I was banging out my own pop tunes. Windows flanked the piano, so whatever I wrote was audible to the world. Even then I worried that if a cab was waiting at the light, the driver might shout up at me: Hey, kid, thats a loser.

Cabbie be damned. I wasnt going to give up my dream of composing for the theatre. Id show em. Just give me another year or two. I was a kid in a hurry. But it took much longer than that. I spent the next thirteen years at Juilliard becoming proficient at playing Bach and Beethoven, hoping all along that Id spend most of my life playing Hamlisch.

Yet years later, with my parents gone, I still heard the voice of my father looking down at me from some celestial plane, with the music of Mozart in the background, saying: Whats the matter, Marvin? By the time Gershwin was your age, he was dead. And hed written a concerto. Wheres your concerto, Marvin? Eerily, it was a question that continued to haunt me even after I had won my Oscars for The Way We Were and The Sting and had written the music for A Chorus Line.

This book is not an autobiography in the conventional sense. How could it be? I feel as if theres still as much yet to be done as has already been done. Besides, I never imagined that one day I might be asked to write a book like this, so I never made notes, kept a diary (only for A Chorus Line), or saved letters. So lets call this a collection of recollections, some good, some not so good, some about my family and the friends Ive made along the way, and some of the work Ive done. The music Ive played and music Ive written trigger memories. Mem-ries, light the corners of my mind

Hmm, I think theres a song in that.

Acknowledgments

I found out that writing a book isnt that much different from writing a song. For when Im finished at the piano, the music needs lyrics to bring it to life. And so it has turned out to be with The Way I Was. I needed collaborators, and, therefore, there are many people to thank.

First is Gerry Gardner, whose contribution was invaluable and whose patience was unending as we kept Federal Expresss profits high and our fax machines humming between Los Angeles and New York.

I owe a deep debt of gratitude to Robert Stewart, my editor at Scribners. He gave freely of his time, and forced me to better understand the way I was. I also must thank Denise Yuspeh Hidalgo for her typing and diligent preparation of the manuscript. A special thank-you to Sam Flores for his meticulous proofreading.

I also want to thank again my beloved parents for giving me such a strong sense of family; my sister, Terry, for her understanding; and my friends and relatives for filling in the gaps in my memory.

Finally, thanks to my wife, Terre, for starting me on the road to new memories.

And to you, dear reader, let me say what I said on Oscar night, 1974, I think we can now talk as friends.

| Marvin Hamlisch |

| New York City, 1992 |

1.

Music Lessons

I know there are more gifted people than me out there. But they may not make it in the music world even if they have the talent, because they dont have the desire and the ego to drive themselves as hard as they can. Or because theyve gotten derailed along the line and cant find their way back to their real goals. Or because they didnt have the parents I had to foster their talents.

Well, I may have had the ego, the drive, and the gift, but I also had parents who fostered like crazy. They fostered me to the school that probably has educated more modern-day musicians than any otherthe Juilliard School of Music. You have to understand more about my parents to know why they enrolled me in the Preparatory Division at age six, the youngest student ever to walk those hallowed halls. They were from Vienna, and my father, Max, would have certainly stayed there if Hitler hadnt had other ideas. Max loved Vienna and was a true Viennese gentlemanthe sort who kissed ladies hands. He loved Old World culture, the music of Schubert, Schumann, Strauss, the cafs, the incredible desserts. But by the mid-thirties, he had a keen sense that it was time for those Jews who could to get out of Europe. My father had been on his way to a successful career as a musician in Vienna, but it was short-circuited by the sudden move to a place where a new language was a barrier.

Arriving in America and not being fluent in English, he found it hard to cope with this frantic new land. Like most Viennese, instead of trying to adapt to New York, he decided to replicate Vienna here. Because he was from the old school, institutions of learning were everything to him. This meant nothing less than his son achieving the success that had been denied him by the fateful march of history.