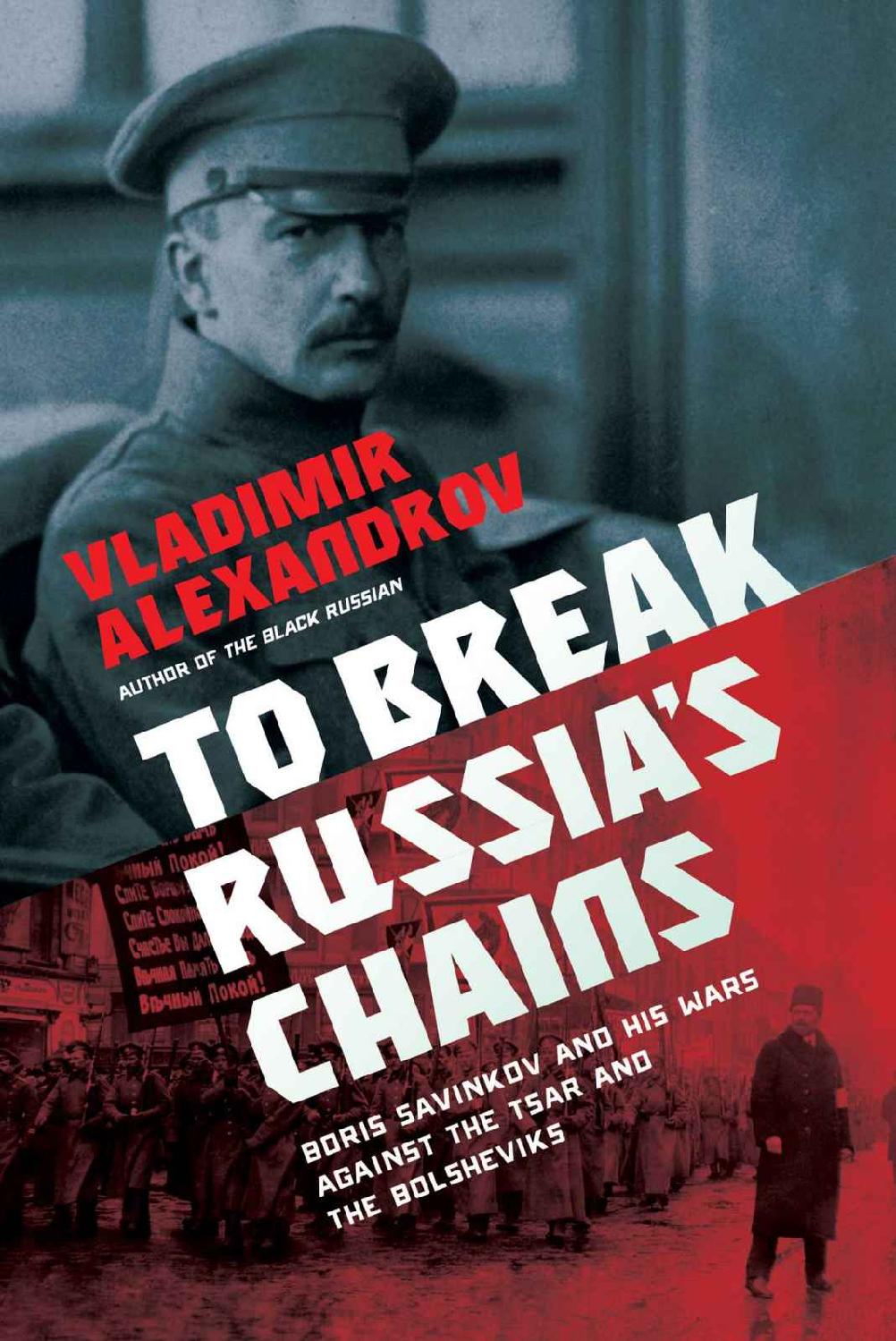

Vladimir Alexandrov

Author of The Black Russian

To Break Russias Chains

Boris Savinkov and His Wars Against the Tsar and the Bolsheviks

For Sybil

Few men tried more, gave more, dared more and suffered more for the Russian people.

Winston Churchill

There is no more sometimes than the trembling of a leaf between success and failure.

W. Somerset Maugham

CONVENTIONS

A ll dates for events in Russia prior to 1918 are given in the Old Style (OS), or Julian, calendar that was used until the beginning of that year and that was thirteen days behind the New Style (NS), Gregorian, calendar used in the West during the twentieth century. During the nineteenth, it was twelve days behind. Occasionally a double date is given for clarity in connection with events that were also important in the West: e.g., Bloody Sunday on January 9/22, 1905, which means January 9 according to the OS calendar and January 22 according to the NS calendar.

There is no single system for transliterating Russian that accomplishes everything one could wish. In the body of the book, I use a system that helps the reader approximate Russian pronunciation. However, in the references I use a system that is conventional in scholarly bibliographies. As a result, the names of some individuals and places appear in two variants, but their equivalence should be obvious (e.g., Moiseyenko = Moiseenko). Well-known names of people and places are given in their most familiar formsthus Nicholas II, not Nikolay II; Saint Petersburg, not Sankt-Peterburg. I also preserve the transliterations of names as used by authors themselves and in references.

Traditional Russian naming practices for people consist of first names, patronymics (derived from the fathers first name), and surnames. For the sake of simplicity, I leave out most patronymics.

Estimates of what different sums of money from the past would be worth in todays dollars are determined by calculators at http://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare.

AUTHORS NOTE

T his is the story of a remarkable man who became a terrorist to fight the tyrannical Russian imperial regime, and when a popular revolution overthrew it in 1917 turned his wrath against the Bolsheviks because they betrayed the revolution and the freedoms it won. If any of the extraordinary plots he hatched against the Bolsheviks had succeeded, the world we live in would be unrecognizable.

Boris Savinkov was famous, and notorious, during his lifetime both at home and abroad because of the major roles he played in all the cataclysmic events that shook his homeland during the first quarter of the twentieth century. The story of his life has an epic sweep and challenges many popular myths about the Russian Revolution, which was arguably the most important catalyst of twentieth-century world history. Although now largely forgotten in the West, Savinkov is still a legendary figure in Russia, and a controversial oneso much so that many documents about him remain locked away in the secret archives of the FSB, the security agency that succeeded the KGB.

It is hard to believe Savinkovs life because of all the triumphs, disasters, twists, and contradictions that filled it. Neither a Red nor a White, he forged his own path through history. He chose terror out of altruism, although what he did bears no resemblance to what terrorism means today. He closely supervised teams of terrorists and agonized over the morality of his actions, but never killed anyone himself. He was a cunning conspirator, but fell victim to the greatest deception in the annals of Russian political skullduggery. He spent years evading the tsars police, but became a government minister during the revolutionary year 1917. He could be as hard as stone and instilled fear and loathing in his enemies, but was admired by international statesmen and became close friends with world-famous artists. He yearned for family life and strived to be a loving husband and father, but sacrificed his personal happiness for political goals. He sent men and women to their deaths, but could recite Romantic poetry for hours and wrote novels and memoirs that are read to this day. He believed in the inviolable rights of human beings, but concluded that only a dictator could guarantee them during periods of great national upheaval. He was fiercely loyal to his comrades-in-arms, but decided to deceive them when he took an immense final gamble in his fight against the Soviet regime. Trying to understand Savinkovs beliefs and the choices he made often forces one to think what might have seemed unthinkable.

Savinkovs life also refracts two issues that remain critically important today: the character of the Russian state and its role in the world. All his efforts were directed at transforming his homeland into a uniquely democratic, humane, and enlightened countryone in which the people control not only their government but also the economic system under which they live, one that welcomes self-determination for all its nationalities, and one that seeks harmonious relations in the international community. The support Savinkov got for his goals from numerous countrymen during his career suggests that the paths Russia took during the twentieth and twenty-first centuriesthe tyranny of the Soviet period, the authoritarianism of Putins regimewere not the only ones written in her historical destiny. Savinkovs goals are a poignant reminder of how things in Russia could have been and how, perhaps, they may still become someday.

Boris Savinkovs life is also an exceptionally good storytoo good to be left untold any longer. All that follows really happened, and everything that is between quotation marks comes from a memoir, a letter, or another historical document.

CHAPTER ONE THE PERSONAL IS ALWAYS POLITICAL IN RUSSIA

T he doorbell rang shortly after 1 A.M. , shattering the quiet just when everyone in the Savinkov household had gone to bed.

Police! a commanding male voice answered the maids anxious question; then, before she could even start unlocking the door, the voice added angrily, Hurry! Open up!

What better time than late at night to ensure that everyone is home and so disoriented by sleep that they cannot resist or even argue effectively? The Gestapo and KGB would perfect the method in the twentieth century, making the dreaded nighttime knock or ringing doorbell the subject of countless nightmares and the herald of millions of disappearances. But in the more innocent nineteenth century, even in the notoriously autocratic Russian Empire, the practice was still too rare for the average person to feel anything but shock and surprise.

It was December 23, 1897, and Boris Savinkov, aged eighteen, and his brother Alexander, twenty-three, had come home for Christmas to the familys apartment in Warsaw earlier that day. Both were university students in the imperial capital, Saint PetersburgBoris was studying law, Alexander mining engineeringand had not seen their parents and four siblings since the beginning of the school year. They had all just spent a wonderfully warm family evening together, talking excitedly, happy to see one another again, the parents filled with delight, marveling at how much their sons had matured in just several months, and very proud of their passionate desire to do something good and important for their country.