Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

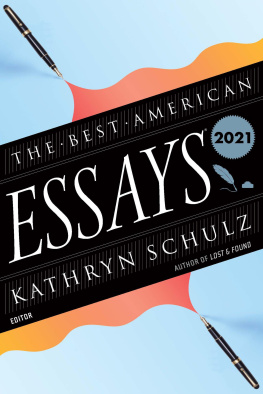

Copyright 2022 by Kathryn Schulz

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Parts of this book originally appeared in The New Yorker in an essay titled When Things Go Missing, published on February 5, 2017.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: Four lines from Close, close all night from Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box by Elizabeth Bishop, edited and annotated by Alice Quinn, copyright 2006 by Alice Helen Methfessel; four lines from One Art from Poems by Elizabeth Bishop, copyright 2011 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Publishers Note and compilation copyright 2011 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All poetry reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved.

Farrar, Straus & Giroux and Faber and Faber Limited: Excerpt from The Trees from The Complete Poems of Philip Larkin by Philip Larkin, edited by Archie Burnett, copyright 2012 by the Estate of Philip Larkin. Digital rights are controlled by Faber and Faber Limited. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux and Faber and Faber Limited. All rights reserved.

HarperCollins Publishers: A haiku of Bashs from The Essential Haiku: Versions of Bash, Buson & Issa edited and with an Introduction by Robert Hass, introduction and selection copyright 1994 by Robert Hass. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Henry Holt and Company: Devotion from The Poetry of Robert Frost by Robert Frost, edited by Edward Connery Lathem, copyright 1928, 1969 by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright 1956 by Robert Frost. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schulz, Kathryn, author.

Title: Lost & found : a memoir / Kathryn Schulz.

Other titles: Lost and found

Description: First edition. | New York : Random House, [2022]

Identifiers: LCCN 2021001420 (print) | LCCN 2021001421 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525512462 (hardcover ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780525512479 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Schulz, Kathryn. | Fathers and daughtersUnited StatesBiography. | LesbiansUnited StatesBiography. | FamiliesUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC HQ755.86 .S38 2022 (print) | LCC HQ755.86 (ebook) | DDC 306.850973dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021001420

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2021001421

International Edition ISBN 9780593446225

Ebook ISBN9780525512479

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Diane Hobbing, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Lucas Heinrich

ep_prh_6.0_138917749_c0_r0

Contents

Nothing includes everything, or dominates over everything. The word and trails along after every sentence.

William James, A Pluralistic Universe

I have always disliked euphemisms for dying. Passed away, gone home, no longer with us, departed: although language like this is well-intentioned, it has never brought me any solace. In the name of tact, it turns away from deaths shocking bluntness; in the name of comfort, it chooses the safe and familiar over the beautiful or evocative. To me, all this feels evasive, like a verbal averting of the eyes. But death is so impossible to avoidthat is the basic, bedrock fact of itthat trying to talk around it seems misguided. As the poet Robert Lowell wrote, Why not say what happened?

Yet there is one exception to this preference of mine. I lost my father: he had barely been dead ten days when I first heard myself use that expression. I was home again by then, after the long unmoored weeks by his side in the hospital, after the death, after the memorial service, thrust back into a life that looked exactly as it had before I left, orderly and daylit, its mundane obligations rendered exhausting by grief. My phone was lodged between my shoulder and my chin. While my father had been in a cardiac unit and then an intensive care unit and then in hospice care, dying, I had received a series of automated messages from the magazine where I work, informing me that I would be locked out of my email if I did not change my password. These arrived with clockwork regularity, reminding me that my access would expire in ten days, in nine days, in eight days, in seven days. It is remarkable how the ordinary and the existential are always stuck together, like the pages in a book so timeworn that the print has transferred from one to the other. I did not fix the password problem. I did lose the access and, with it, any means to solve the problem on my own. And so, after my father died, I found myself on the phone with a customer service representative, explaining, although it was absolutely unnecessary to do so, why I had neglected to address the issue in a timely fashion.

I lost my father last week. Perhaps because I was still in those early, distorted days of mourning, when so much of the familiar world feels alien and inaccessible, I was struck, as I had never been before, by the strangeness of the phrase. Obviously my father hadnt wandered away from me like a toddler at a picnic, or vanished like an important document in a messy office. And yet, unlike other oblique ways of talking about death, this one did not seem cagey or empty. It seemed plain, plaintive, and lonely, like grief itself. From the first time I said it, that day on the phone, it felt like something I could use, as one uses a shovel or a bell-pull: cold and ringing, containing within it both something desperate and something resigned, accurate to the confusion and desolation of bereavement.

Later, when I looked it up, I learned that there was a reason lost felt so apt to me. I had always assumed that, if we were referring to the dead, we were using the word figurativelythat it had been appropriated by those in mourning and contorted far beyond its original meaning. But that turns out not to be true. The verb to lose has its taproot sunk in sorrow; it is related to the lorn in forlorn. It comes from an Old English word meaning to perish, which comes from an even older word meaning to separate or cut apart. The modern sense of misplacing an object only appeared later, in the thirteenth century; a hundred years after that, to lose acquired the meaning of failing to win. In the sixteenth century we began to lose our minds; in the seventeenth century, our hearts. The circle of what we can lose, in other words, began with our own lives and each other and has been steadily expanding ever since.

This is how loss felt to me after my father died: like a force that constantly increased its reach, gradually encroaching on more and more terrain. Eventually I found myself keeping a list of all the other things I had lost over time as well, chiefly because they kept coming back to mind. A childhood toy, a childhood friend, a beloved cat who went outside one day and never returned, the letter my grandmother wrote me when I graduated from college, a threadbare but perfect blue plaid shirt, a journal Id kept for the better part of five years: on and on it went, a kind of anti-collection, a melancholy catalogue of everything of mine that had ever gone missing.