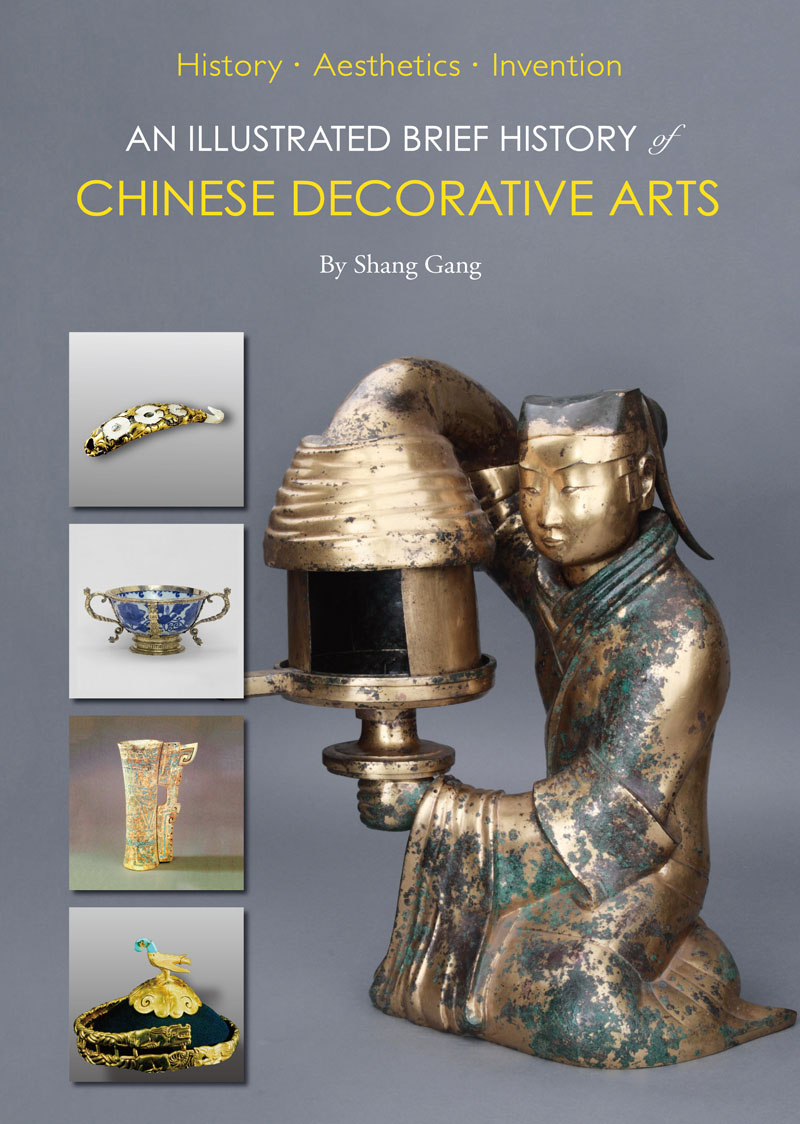

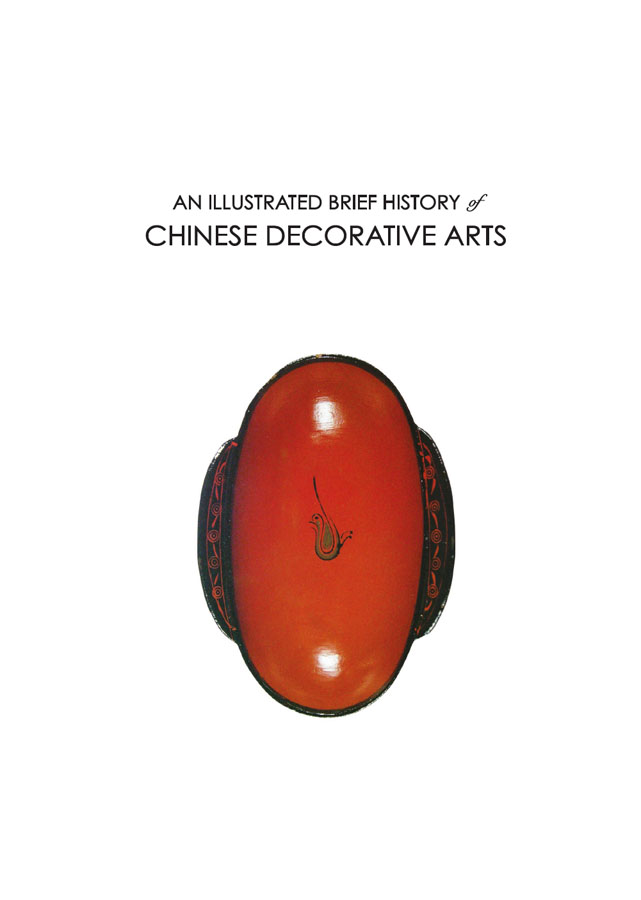

Fig. 1 Lacquer E ar Cup Painted with Phoenix Pattern

Mid-Western Han dynasty (202 BCAD 8)

Height 4.2 cm, rim length 14.6 cm

Jingzhou Museum, Hubei

Unearthed from Tomb No. 28 at the raised burial site at Jiangling, Hubei in 1992. The phoenix pattern, a potent symbol, is painted vividly in a simplistic style. The concentric circles on the handles to the sides were likely created by impression method.

On

Fig. 2 Famille Rose Flattened Vase with Floral and Bird Motifs

Yongzheng reign (17221735) of Qing dynasty (16441911)

Height 29.4 cm

The British Museum, London, U.K.

This piece is the most representative of famille rose porcelain produced during the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (16781735). Prior to the British Museum, it was in the collection of Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art that has some of the finest Chinese ancient porcelain wares.

On

Fig. 3 Lobed Bronze Mirror Decorated on the Back with Gold and Silver Inlay on Lacquer

Ca. 650755 of Tang dynasty (618907)

Diameter 28.5 cm, rim band width 0.6 cm, weight 2,935 g

The Shosoin Repository (North Section), Nara, Japan

This Tang era mirror is in the Shosoin Repository of the Japanese royal house, which has a large collection of artifacts dated to the mid-8th century, well-preserved to this day according to strict conservation rules.

On

Fig. 4 Zitan (Purple Sandalwood) Weiqi Game Board with Marquetry

Ca. 650755 of Tang dynasty

Length 49 cm, width 48 cm, overall height 12.6 cm

The Shosoin Repository (North Section), Nara, Japan

Inside each of the two drawers is a tortoise-shaped bowl holding weiqi pieces. The game board is similar to that of the modern design, with some variations.

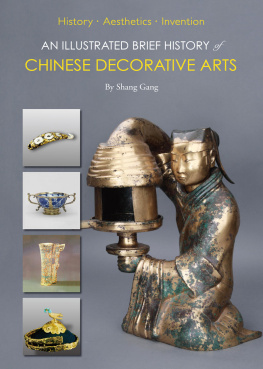

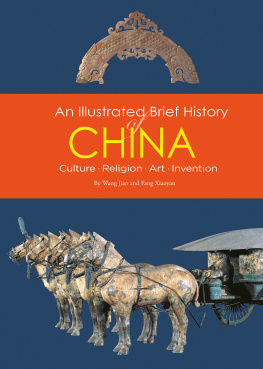

Copyright 2022 Shanghai Press and Publishing Development Co., Ltd.

All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction, in any manner, is prohibited.

This book is edited and designed by the Editorial Committee of Cultural China series.

Text and Image by Shang Gang

Translation by Liu Haiming

Cover Design by Wang Wei

Interior Design by Li Jing and Hu Bin (Yuan Yinchang Design Studio)

Editor: Wu Yuezhou

Editorial Director: Zhang Yicong

ISBN: 978-1-93836-855-4

Address any comments about An Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Decorative Arts: History Aesthetic Invention to:

SCPG

401 Broadway, Ste. 1000

New York, NY 10013

USA

or

Shanghai Press and Publishing Development Co., Ltd.

390 Fuzhou Road, Shanghai, China (200001)

Email:

Printed in China by Shanghai Donnelley Printing Co., Ltd.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

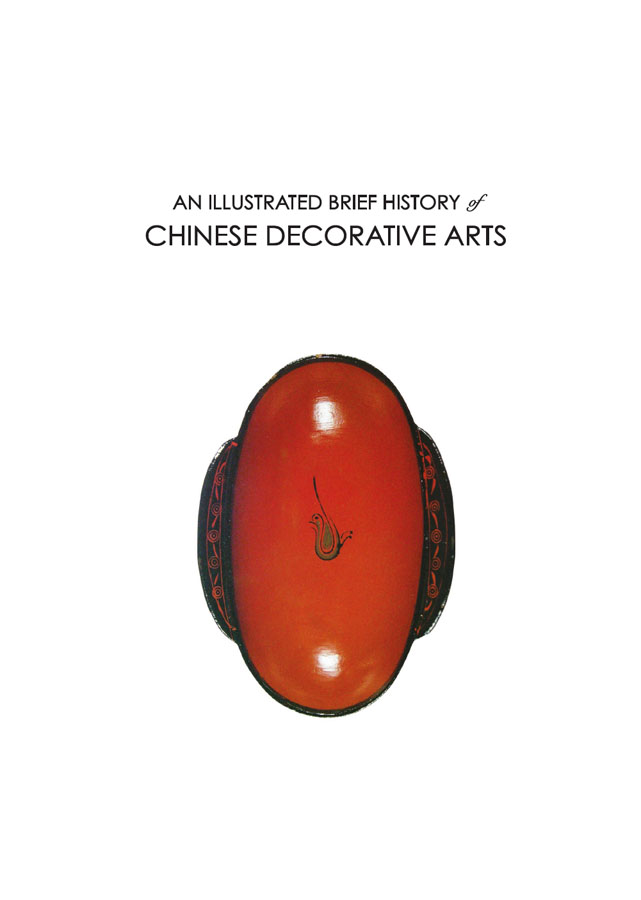

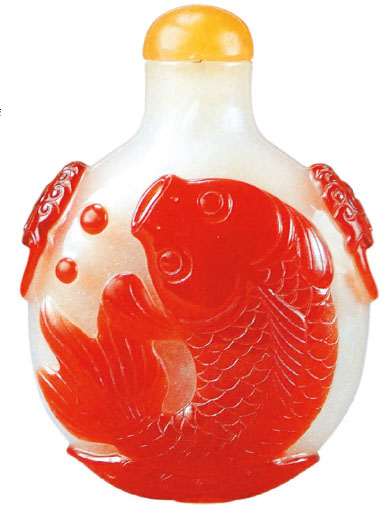

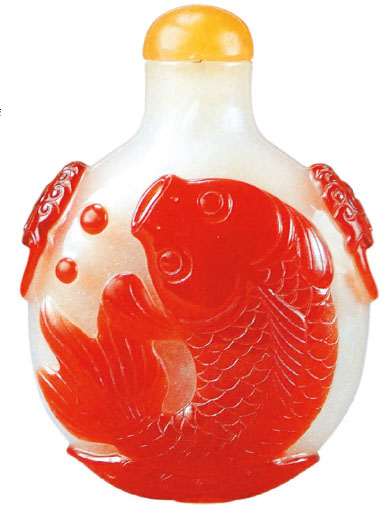

Fig. 5 Glass Snuff Bottle with Overlay Fish Pattern

Mid-Qing dynasty

Height 6.5 cm, width 5.3 cm

The Palace Museum, Beijing

Fish has been an auspicious symbol since ancient times, as the word for fish is homophonic in Chinese with abundance and wealth. The fish overlaid on the bottle is pleasingly plump; joyous and propitious in effect.

CONTENTS

Fig. 6 Please refer to .

FOREWORD

ANCIENT CHINESE DECORATING ART AND ITS UNIQUE CHARACTERISTICS

Fig. 7 Pottery Jar Painted with Crane, Fish and Stone Axe

Miaodigou phase, Yangshao Culture (ca. 5000ca. 3000 BC)

Height 47 cm, rim diameter 32.7 cm, base diameter 19.5 cm

National Museum of China, Beijing

Dating back about 6,000 years, it was unearthed at a burial site near Yan Village, Linru, Henan in 1978. It has the largest painted surface among extant ancient pottery in China. The crane image is the oldest known example of a technique called mogu painting (boneless, without the usual strong brush outline).

T he term decorative art refers to any of the plastic arts created by handcraft means. The origins of Chinese decorative art date back eight millennia, if discounting ornamental objects found from even earlier times, representing the earliest of artistic achievements at the dawn of Chinas Neolithic Age spanning four millennia. The early media mastered included pottery and textile, in addition to stone tools crafted by grinding and polishing. While textile materials were perishable and extant items rare, stone, jade, and pottery artifacts that have survived to this day in abundance bear witness to the artistic creativity of our ancient forebears. Throughout Chinese primitive societies, decorative arts showed a greater maturity and had more glorious achievements than fine arts. Painting () were often means of decoration for handcrafted utilitarian items.

What then is decorative art? If defined by its mediatextile, ceramics, jade, metals, lacquered wood and miscellaneous (bamboo, animal tusks or horns and glass), rather than by any other debatable terms, objects of decorative art are chiefly prized for their utility and secondly decorative appeal. Yet, the line between function and beauty is often hard to draw. Items for everyday use can be visually pleasing, while those for admiration may also serve a practical purpose, except that the latter may use better materials and be more exquisitely crafted.

Fig. 8 Black Pottery Zun in Hawk Shape

Miaodigou phase, Yangshao Culture

Height 36 cm

National Museum of China, Beijing

Predated slightly by the painted pottery jar in , this wine vessel (zun) was unearthed from a burial site at Taipingzhuang in Huaxian, Shaanxi in 1975. Fashioned into the shape of a hawk, the ample and masculine form, emblematic of its owners noble status, shows amazing sculpting prowess.

1. The Utility Principle

With rare exceptions, usefulness is central to objects of decorative art, with their shape and decorative design serving functional needs. China in ancient times remained primarily agrarian. Specimens of decorative art from antiquity are thus solid and sturdy, made for easy storage or display, in keeping with the settled agrarian life. In periods under nomadic rulers reign, portable items designed for the nomads way of life became more widely available. As the conquering nomads settled down, the design and style of their everyday-use objects evolved, as shown in the pottery pilgrim flasks dated to the Liao dynasty (9161125) ().

Other design features were related to functionality, too. A wine pot, for example, could have a matching warming bowl (), but never a teapot. For tea was always brewed in hot water while wine could be cold out of the container and require warming up for drinking. Larger wine vessels were always for libation of a mild nature, while smaller ones that of higher alcohol content. Decoration, on the other hand, was not as closely related to functionality. Yet the shift towards painted decoration, as opposed to engraving or sculpting, had something to do with its ease of cleaning. Thus, underglaze painting on ceramics became prevalent in and after the Yuan dynasty (12711368).

Next page