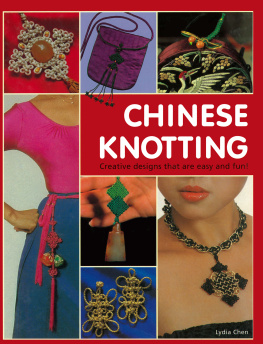

Chinese Knots in Ancient Times Chinese knotting, ancient as it may be, was never the subject of scholarly treatises and there are only passing references to it in the literature. Some scholars believe this is because the early Chinese looked down on science, technology and the folk arts, believing that Philosophy is the Way, and all others are just tools. Yet, the complexity and ingenuity of the knots that have survived from the late Qing and early Republican periods as well as tantalizing secondhand evidence from sculpture, stone carvings, paintings and poetry testify to the culmination of a long, unbroken artistic tradition that may possibly have predated the written record. From early times, knotting was one of the most basic skills that Man needed for survival. It was only after knotting techniques were developed to bind two or more things together that he could invent a variety of tools for hunting and fishing, such as bows, arrows and nets. Mankind went on to make farming tools, such as hoes and shovels, by fastening stones to wooden sticks, which led, in turn, to the construction of shelters using cords to bind the different members together, and the development of other inventions to aid production and convenience.

Eventually, knotting became developed for communication purposes, to exchange letters and numbers and to record events. The art of knotting gradually found its use in decoration and rituals, firmly establishing itself as an important part of traditional handicrafts. Using Cords to Record Events Although it is difficult to envisage, there is sufficient documentary evidence to show that the ancient Chinese recorded events with cords. In a commentary by an early scholar, Zhou Yi, on the trigrams of the Yi Jing or Book of Changes , the oldest of the Chinese classic texts, which describes an ancient system of cosmology and philosophy that is at the heart of Chinese cultural beliefs, he says that in prehistoric times, events were recorded by tying knots; in later ages, books were used for this. In the second century CE , the Han scholar Zhen Suen wrote in his book Yi Zu , Big events were recorded with complicated knots, and small events, simple knots. no writing, hence must carve on woods and tie cords.... no writing, hence must carve on woods and tie cords....

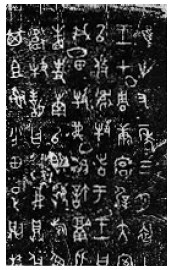

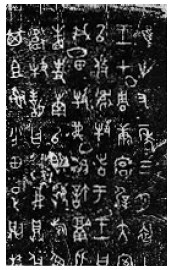

Moreover, the chapter on Tufan in the New Tang Chronicle reveals that due to a lack of writing, the ancient Chinese tied cords to make agreements. This was practiced in other countries as well. For example, in Peru, there was a similar system called Qui pu, whereby a single knot means 10, a double knot 20, and multiple knots 100. Special government officials were available to explain the knots. The only indigenous evidence of this practice of making records with knotted cord consists of simple pictorial representations of the symbolic use of knotting on the surface of bronzeware from the Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).  Calligraphy from the 27th year of Emperor Weis reign.

Calligraphy from the 27th year of Emperor Weis reign.  Calligraphy from the 31st year ofEmperor Weis reign.

Calligraphy from the 31st year ofEmperor Weis reign.  Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).

Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).  Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).

Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).

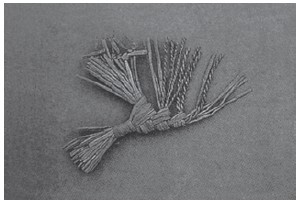

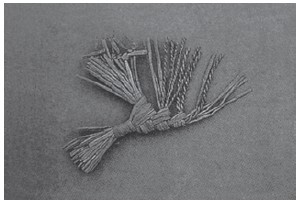

Knots in Stone Carvings and Fabric Paintings The double coin knot is the oldest knot to be recorded, although the prototype, a series of vertical double coin knots found on a pedestal box excavated from Zhao Qings tomb in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province (page ). In terms of structure, the button knot and double coin knot belong to the same system; the former is, in fact, a variation of the latter.  Cords tied in this way show the number of cattle, goats and horses in Okinawa, Japan. This indicates a total animal count of 188.

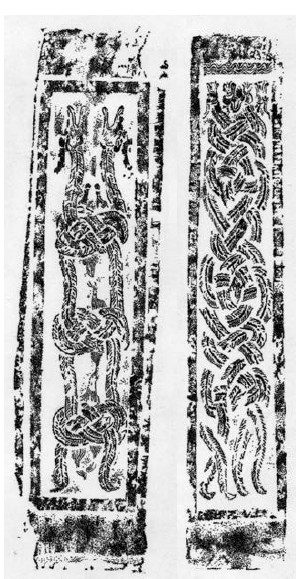

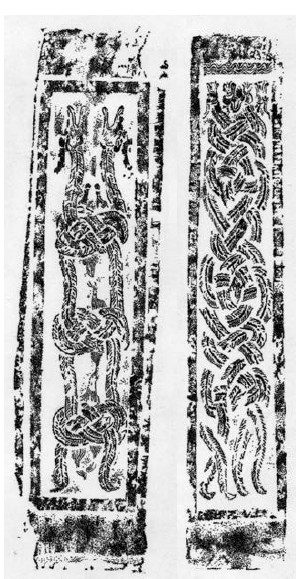

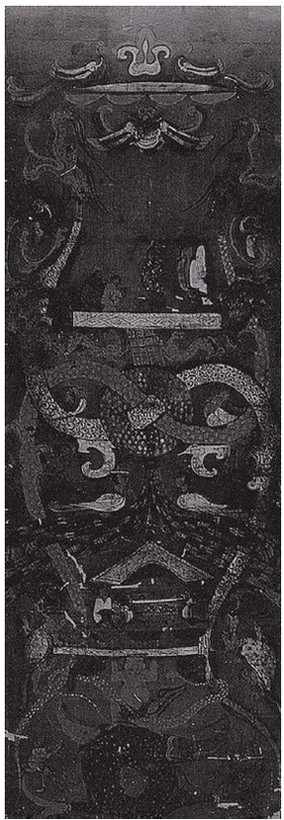

Cords tied in this way show the number of cattle, goats and horses in Okinawa, Japan. This indicates a total animal count of 188.  Part of a fabric painting depicting two dragons intertwined in the shape of a double coin knot, Western Han Period (206 BCECE 8), from Ma Wangs Tomb, Changsha, Hunan Province.

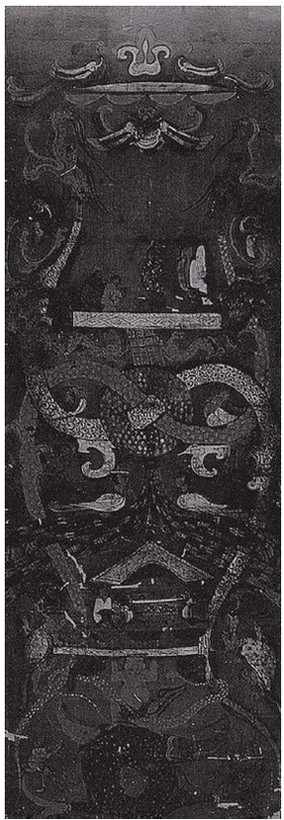

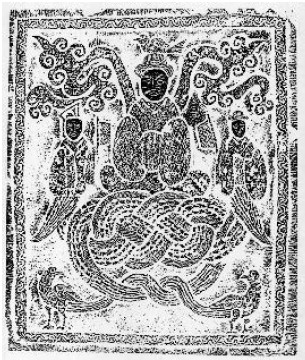

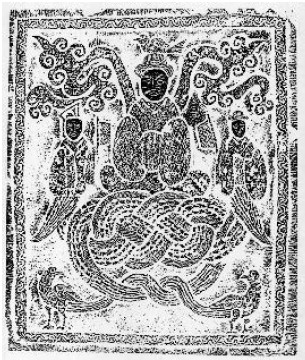

Part of a fabric painting depicting two dragons intertwined in the shape of a double coin knot, Western Han Period (206 BCECE 8), from Ma Wangs Tomb, Changsha, Hunan Province.  Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.

Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.  Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.

Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.

The Poetic Use of Chinese Knots According to the Ci Hai dictionary, a knot is the hook-up of two cords, and hence the knot has always been euphemized as the love between a man and a woman. The famous Tang Dynasty poet Meng Jiao wrote in his poem Knotting Love: One knot after another

Knotting true and deep love

Upon my loves departure

I make a thousand knots on his sleeve

I swear to wait faithfully

Hope these knots will prompt him to come home early

But whats the use of tying knots on his garment?

It is better to knot our hearts together

We knot our hearts in whatever we do

We knot our hearts for eternity The love knot has always been synonymous with true love. The Ci Hai goes on to explain that In ancient times, gold cords were intertwined countless times to signify true love, and thus were appropriately euphemized as the love knot. Among Chinese knots, the double coin knot most resembles the love knot, another reason for us to extrapolate that the love knot mentioned in ancient poems is actually todays double coin knot. Indeed, the love knot is the earliest knot mentioned in ancient poems, such as Yu So Si by Emperor Liangwu of the Southern Dynasty, Dao Yi by one of Chinas most renowned poets, Li Bai, Willow by Liu Yu Xi, Farewell Song by Wang Jian, Spring in Wulin by Ou Yang Siu and To the Pipa Girl by Li Qun Yu. In each case, the poet revealed his love with the love knot.

In Meng Liang , Wu Zhimu wrote that in ancient marriages, the red cloth covering the brides face was graced with a double love knot, as were the bride and bridegrooms wine cups, which were quickly drained and turned upside down under the bed for good luck. Besides the love knot, there is the happy together knot mentioned in Emperor Liangwus poem The Autumn Song. We do not know what the happy together knot looks like. However, the History of the Liao Kingdom mentions that every year, on May 5th, the Liao people tied cords of five different colors on their arms and called this the happy together knot. Given that the Han and Liao used their knots for different purposes, the two happy together knots may be altogether different. There is a third knot that is quite similar to the love knot, the pair knot.

In his poem Jie Yang Chang, Jie Xi Si of the Yuan Dynasty mentioned the pair knot. Also, Li Bai, in his poem Dai Zheng Yuen, talked about another knot which he euphemized as the huiwen knot. It is likely that this huiwen knot is actually the love knot, a case of a single entity with two names.

Calligraphy from the 27th year of Emperor Weis reign.

Calligraphy from the 27th year of Emperor Weis reign.  Calligraphy from the 31st year ofEmperor Weis reign.

Calligraphy from the 31st year ofEmperor Weis reign.  Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).

Jade xi tools in the shape of a phoenix and dragon, Warring States Period (475221 BCE ).  Cords tied in this way show the number of cattle, goats and horses in Okinawa, Japan. This indicates a total animal count of 188.

Cords tied in this way show the number of cattle, goats and horses in Okinawa, Japan. This indicates a total animal count of 188.  Part of a fabric painting depicting two dragons intertwined in the shape of a double coin knot, Western Han Period (206 BCECE 8), from Ma Wangs Tomb, Changsha, Hunan Province.

Part of a fabric painting depicting two dragons intertwined in the shape of a double coin knot, Western Han Period (206 BCECE 8), from Ma Wangs Tomb, Changsha, Hunan Province.  Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.

Rubbing from a stone carving depicting the Superior Mother Goddess, Deity Fu Xi and Goddess Nu Wo intertwined in a dragons body in the shape of a double coin knot, Eastern Han Period (CE 25 220), from Tung Wei Mountain.