First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Edward Denison

The right of Edward Denison to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

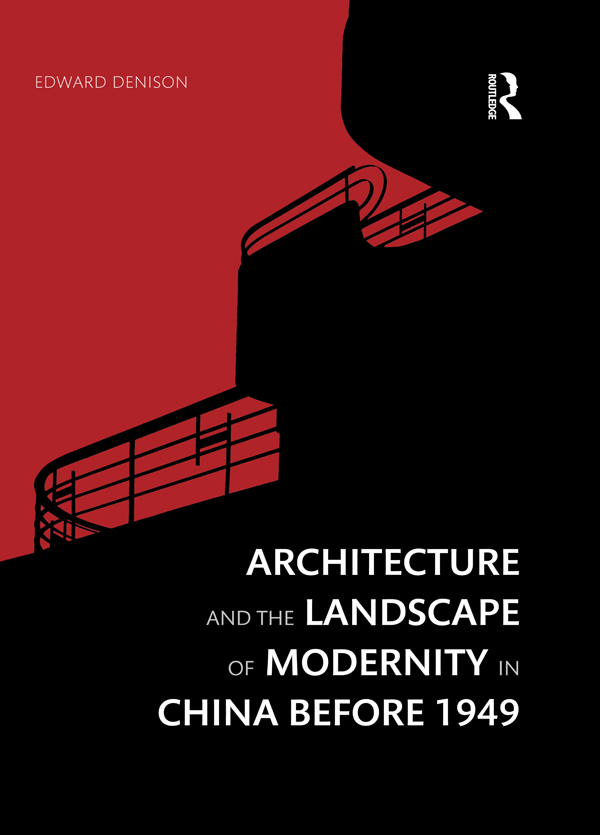

Names: Denison, Edward, author.

Title: Architecture and the landscape of modernity in China before 1949/

Edward Denison.

Description: New York: Routledge, 2017. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036629| ISBN 9781472431684 (hardback) |

ISBN9781315567686 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Modern movement (Architecture) China. | Architecture and

society China History 20th century.

Classification: LCC NA1545.5.M63 D46 2017 | DDC 720.1/03 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036629

ISBN: 9781472431684 (hbk)

ISBN: 9781315567686 (ebk)

Typeset in Sabon

by Florence Production Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon, UK

Through the great Gate

Along the towered Wall

By banks where ducks preened in the winter sun

We rode.

You lifted the reins.

Swiftly you drew away.

Your cry came back in the wind.

That Gate, that Wall are levelled.

Wind stirs the dust.

Wind whispers the echo

of you to me

of me to you.

(Poem by Wilma Fairbank to Phyllis Liang

(Lin Huiyin) c.1958, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts)

This book is the culmination of nearly two decades of collaboration with so many people around the world it is almost impossible to recall everyone who has offered me their support. I am indebted to you all: Guang Yu, Ella, and George, Eleanor and John, Hou and Ren, and Alexa, John, Henry, Zoe, and William, and Nancy Berliner, Ed Bottoms, Lily Brett, Lin Ci Brown, Helen Castle, Judith Cligman, Patrick Cranley, Kerri Culhane, Ding Feng, Carma Elliot, Holly Fairbank, Fan Li, Adrian Forty, Murray Fraser, Paul French, Michelle Garnaut, Cathy Giangrande, Susie Gordon, the Hansons, Lenore Heitkamp, Peter Hibbard, Alan Hollinghurst, Tess Johnston, Tina Kanagaratnam, Dr Luk Shing Chark, Men-Ching Luk, Men-Chong Luk, Henry Ng, Lynn Pan, Karolina Pawlik, David Rankin, Peg Rawes, Margaret Richardson, Valerie Rose, Prof. Ruan Yisan, Daphne Skillen, Shinnosuke Takayanagi, John Stubbs, Tom Weaver, Wang Haoyu, Anne Witchard, Jennifer Wong, Frances Wood, Shixuan Ying, Prof. Zheng Shiling, countless libraries and librarians throughout China, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, The British Council, The Peabody Essex Museum, The Royal Asiatic Society, The World Monuments Fund, and last but by no means least all my students and colleagues at The Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL), for challenging and supporting my research.

The author owns the copyright of the maps ().

7

Modernism and nationalism

In 1927, the same year that the Nationalists united China, the British author and journalist, Arthur Ransome, observed: Every blow struck by foreigners in China is a blow in the welding of a nation. Unintentionally metaphorical, his words echo the relationship between building construction and nationalism in China. Whereas in many countries outside the west, nationalism became a potent force only after the Second World War, nationalism in China was fully developed much earlier, and significantly altered the nations encounter with modernity and architecture.

Nationalism and national identity occupy a central position in studies of early twentieth-century architecture in China and are relatively well-researched topics that were acknowledged to be important to Chinas architects. However, consistent with this studys perspective, these familiar subject territories will be approached differently and with fresh evidence that challenges certain established perceptions. For example, the denotation of the ubiquitous term first generation of Chinese architects, referring to the American-trained Chinese architects of the 1920s is questioned, casting doubt on some of the other received ideas about Chinas encounter with modernity. Also challenged here is the privileged historical status given to architects that chose to remain in China after 1949; their careers have received disproportionate consideration in subsequent scholarship. Just as some painters and writers who fell out of favour during subsequent political currents have fallen into obscurity, so too have the work and careers of many architects associated with pre-1949 China been ignored, deliberately or otherwise. Chinas history is further complicated and distinguished from most countries outside the west by its partial colonisation. Notwithstanding Japanese imperialism and the quasi-colonial status of many of Chinas major cities, the integrity of China as a nation-state was seldom questioned, albeit frail and fragmented between the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of a Nationalist government, which was largely successful in securing a degree of sovereignty from 1927, even after the Japanese invasion of 1937 that forced the Chinese to retreat to the proxy capital of Chongqing. The greatest threat to national unity came not from any external pressure but from the internal struggle between the Nationalists and the Communists, a conflict that began in the 1920s and whose persistence into the twenty-first century continues to distort historical accounts.

Defining nationalism in the context of China is therefore complicated by both domestic and international circumstances. As discussed earlier, national unity derived less from notions of modern statehood than from a sense of Chinas enduring civilisation. Nationalist discourses were therefore invariably framed by the question of what it meant to be Chinese, rather than promoting the concept of China. For China, civilisationism , rather than nationalism , might be a more appropriate term, though this awkward neologism will be acknowledged only in spirit when referring to nationalism here.

A national architecture

National identity has often been claimed through building. Observers interpret from architecture the features that they assert denote national characteristics. These are either accepted or rejected, but over time come to characterise and reinforce the world in ways that literature, poetry and painting do not and cannot. Nationalism therefore can be a cogent force in embodying the ideas or aesthetic values ascribed to a nation both actively, in the mind of the architect, and reactively, in the eyes of the viewer.

Architecture has by its very nature always been exposed to a wider and less select audience than the outputs of other art practices. Consequently, its potential to manipulate the cause of nationalism negatively or positively was often greater than that of any other form of art a fact that did not go unnoticed among Chinas political elite. The paradox for China, as with many places outside the west, is that architecturally, nationalism and the study of the nations built heritage that helped to define a national architectural style were contemporaneous with modernism, in contrast to the west where architectural historical research long pre-dated modernism, and where modernism was explicitly internationalist.