Pagebreaks of the print version

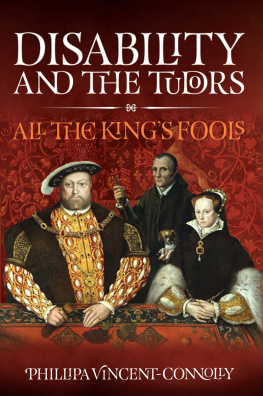

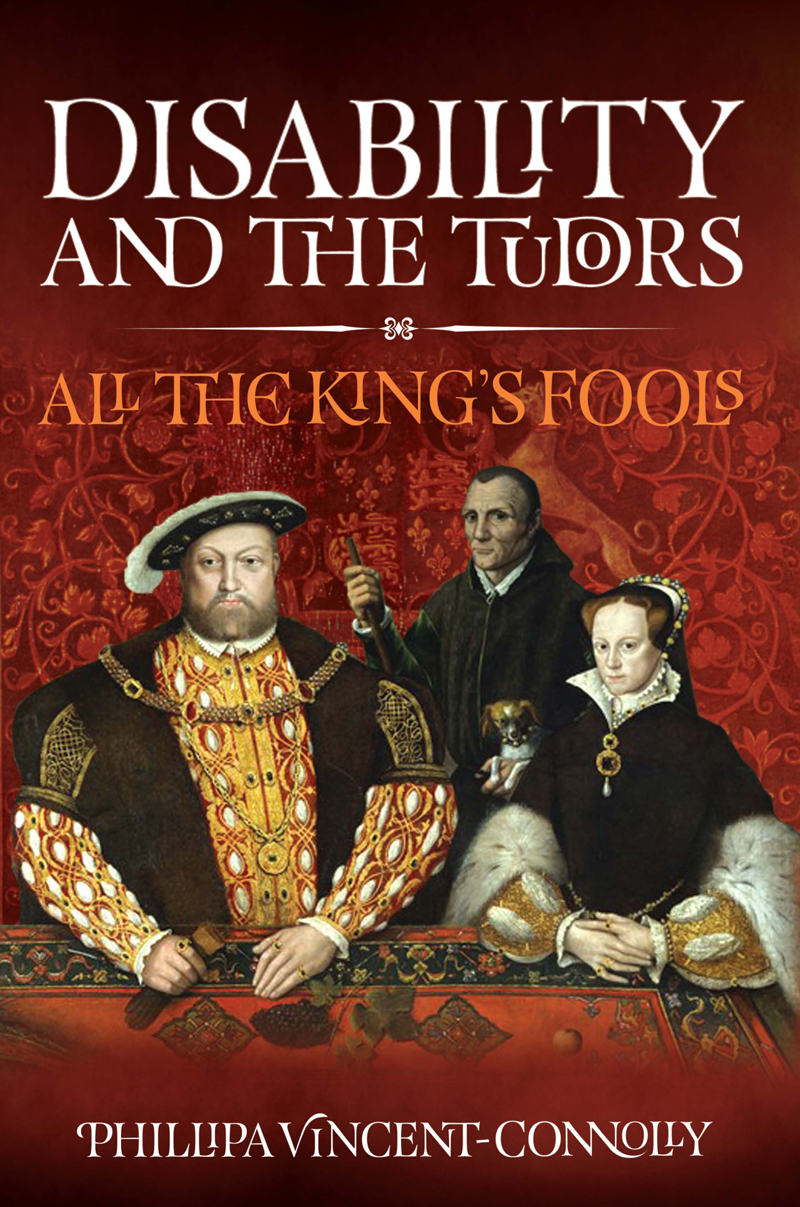

DISABILITY

AND THE TUDRS

In memory of my Dad, Robin John Vincent

DISABILITY AND THE TUDRS

ALL THE KINGS FOOLS

PHILLIPA VINCENT-CONNOLLY

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Phillipa Vincent-Connolly, 2021

ISBN 978 1 52672 005 4

eISBN 978 1 526 72007 8

The right of Phillipa Vincent-Connolly to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com .

Introduction

The existence of participants.

history is important to address specifically because the subject is often viewed as taboo, and as such, has, and still is often obscured from public view, understanding, and awareness. Disability studies is a field. It is considered a subject in its own right in some universities around the world, but not all. It is not adjacent to English, Sociology or History but should be considered as a subject in its own right. Disability studies deserve whole departments and dedicated faculty members, so the subject can be treated as an interdisciplinary field, rather than a crosslisted posting. Yet, academics and researchers continue to treat disability studies as a last-minute topic, something that they can add-on to their research to be on top of the trends in academia. Sadly, this trend in studying minority histories does a disservice to those disabled people we study, research and write about. Disabled people are equally part of humanity and they give us a different perspective on what it means to be human.

Disabled people and their histories have been overlooked, and their stories so often whitewashed in the narrative of this country, yet they are vital to our real understanding of the past.

Moreover, disability narratives during the Tudor period were subtly ignored, yet hidden in plain sight. Extraordinarily, however, at the same time, a select few disabled people were on public view, because Hampton Court Palace is littered with paintings that suggest, and prove indeed, disability was very much an included part of royal life. Disabled people then, like today, were found in all aspects of Tudor society and therefore their inclusion and relevance are a vital component in our developmental history, which is why the subject needs to be addressed.

However, there is a downside to researching disability history during this period because the Tudors did not categorise disabilities, and they were only just beginning to classify and compartmentalise both physical and mental disabilities. The Tudor viewpoint towards disability is one of contrasts: , perhaps incapable of sin. Interestingly, the Tudors also valued extremes of physical disability, such as dwarves and giants.

The use of disability in Shakespearean texts suggests that the words disability and disabled were used in three contexts during the Tudor era. First, in the legal sense to disable meant to hinder or restrain, a person or class of persons, from performing acts or enjoying rights which would otherwise be open to them.

These contexts on disability, reinforce the definitions of disability within the Equality Act 2010, which states that if a person has a physical or mental impairment that has a substantial and long-term negative effect on their ability to do normal daily activities, then they are considered disabled. It is from this definition of disability that the research in this book is based.

Shakespeares use of the word disability suggests that: The verb disable was first used in the legal sense in 1445, and then later in the medical sense around 1492, but the verb was not used in a conceptual sense until 1582. Disability the noun was used in the conceptual sense in 1545, in the medical sense in 1561, and in the legal sense in 1579. Disabled the adjective was used in the conceptual sense in 1598, but not in the medical sense until 1633. Additionally, the disabled as an adjective with a definite article referring to a class or group of people did not appear until 1740.

The definition of disability was undefined, yet the existence of disabled people was viewed as a common occurrence in everyday early modern life. Therefore, disabled people and their experiences of specific disabilities were rarely recorded, which means that case studies and anecdotal evidence for the researcher are very limited. In order to broaden the research, because the Tudors did not place disability within any category, and left disability uncharacterised, definitions of disability need to be compared and contrasted to those in our modern world.

Today, we have definitively defined disability through the Equality Act 2010. Disability has also been defined over the years by medical practitioners into different types of physical and mental categories. Specifics such as these help us to understand how we can help disabled people today. To encapsulate the research, the evidence in this book is viewed through the lens of a Tudor persons ability or inability to take part in normal daily activities that contemporary society considered part of everyday life. It was these expectations of people in that society and their inhibited abilities that would have rendered them disabled, without classifying them as such. It is with this dilemma that this book came into being.

Despite the voracious appetite for everything Tudor, we think we know everything there is to know about them with English History being so familiar across the globe. Early in 2020, Henry VIIIs ex-wives arrived on the Broadway stage in the musical Six , Divorced, Beheaded, Live in concert!, and tourists and history enthusiasts buying B pendants, sold at Hampton Court Palace, and Tudor Royal Doulton figurines, found at car boot sales. The Tudors are bigger than ever. Again. Our fascination with the Tudors and every aspect of their dynasty is satisfied and commercialised with a plethora of products. Primary sources are debated and deliberated over by historians, yet Tudor disability history is yet to be discovered, and the existence of disabled people during the Tudor period is still unfamiliar to many of us.