Contents

Guide

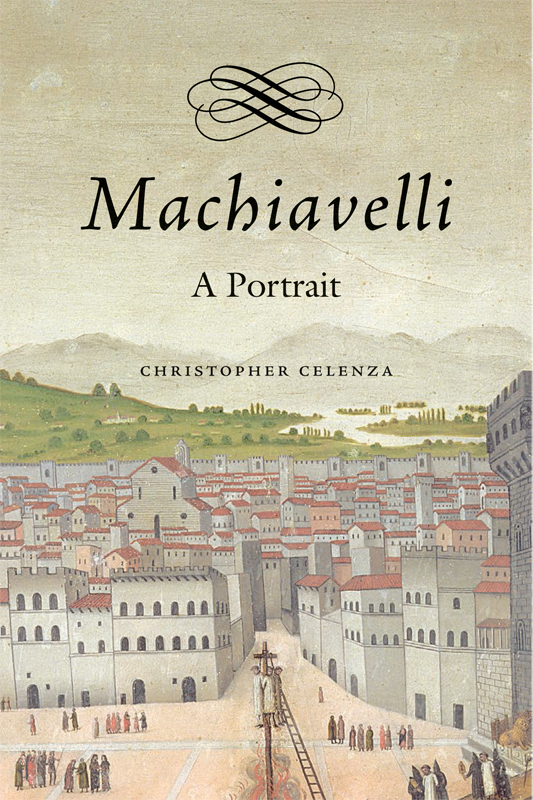

Machiavelli

A Portrait

CHRISTOPHER S. CELENZA

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2015

Copyright 2015 by Christopher S. Celenza

All rights reserved

Jacket art: Anonymous, Savonarola Being Burned at the Stake, Piazza della Signoria, Florence (oil on panel, sixteenth century), Bridgeman Art Library

Jacket design: Graciela Galup

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

ISBN (print): 978-0-674-41612-3

EPUB: 978-0-674-42521-7

MOBI: 978-0-674-42520-0

PDF: 978-0-674-42519-4

For Anna Harwell Celenza

Contents

Machiavelli. His name conjures up a vision of amoral conduct and the idea that the ends justify the means in everything from introductory political science classes to business manuals. These days he appears as a character in a wildly popular role-playing video game, Assassins Creed, and he was a regular in Showtimes hit television series The Borgias. Pair the word Machiavellian with the name of almost any politician in an Internet search, and you will find a whole world of journalism to explore. Why are we so fascinated by him? Why has his name retained such a powerful hold on our imaginations?

The answer is found in The Prince, a short book he wrote in 1513. Though it was unprinted in his lifetime, The Prince went on to become an enduring bestseller, translated into numerous languages. Is it better to be loved or feared? How much does fortune influence human affairs? Should a leader be impetuous or measured? How do leaders plan for the future when there are always so many possible paths to take? How much do appearances matter? Machiavellis answers to these and many other questions emerge in The Prince. It is the Italian Renaissances most famous book, and it deserves the attention it has traditionally received. But it had a context. At first glance, the circumstances that led to the composition of The Prince seem almost unbelievable.

The year was 1512. Machiavelli, an active diplomat and political figure in Renaissance Florence, found himself and his city immersed in wars, tumultuous politics, and conspiracies. The Medici family had not been part of Florences government since 1494. But after a good deal of back and forth, the Medici returned to Florence with Spanish backing. Machiavellis name was discovered on a list of possible anti-Medici conspirators. He was arrested, imprisoned, and subjected to the strappado, that ingenious form of torture whereby your hands are tied behind your back, you are lifted up into the air by a rope on a pulley, and you are then dropped almost, but not quite, to the ground. At that final moment, the rope is jerked tight, and your arms almost come out of their sockets. Machiavelli was dropped six times.

Giovanni de Medici, the son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, had been made a cardinal when he was a teenager. On March 9, 1513, he became pope. Amid the celebrations in Florence, an amnesty was declared, and the authorities released Machiavelli from prison on the condition that he remain in Florentine territory. So he went to a small family property in the countryside outside of Florence, and there he began to write what became The Prince.

Understood within the development of a life lived with such drama, as was Machiavellis, with ups and downs that few of us could fathom or would want to consider, it is all the more impressive. And when we realize that Machiavellis writings cover so much more than what is in The Princethat he wrote histories, treatises on politics, even comedies, and that before he wrote these works he had a substantial political and diplomatic careerwe are propelled to find his origins, to see what shaped him, to tell the story of his life. Only then can a clear portrait emerge, a portrait that, like all such endeavors, must be selective in order to communicate the essence of the subject.

1

MACHIAVELLIS LITTLE-KNOWN YOUTH

If you are reading this book, you have probably never witnessed a public execution or been close to someone who has. Most likely, you have not been physically tortured during legal proceedings. And in all probability you dont live in a world where war is on your doorstep, literally, not outsourced and far away. Finally, in the course of your education, you were almost certainly not taught in a language that was neither your mother tongue nor a living languagebut rather Latin. These are just some ways your world differs from that of Niccol Machiavelli. The world you inhabit was not his world.

What was his world like? What did Machiavelli see, growing up in Florence? What did he learn? Why did Machiavelli express himselfin his language, style, and vocabularyas he did? Biography, culture, and politics all played a role.

He was born in 1469 to Bernardo Machiavelli and Bartolomea de Nelli. Bernardo possessed an advanced degree in law, and though not especially well off financially, he was a cultured man. Like many Florentines of his station, he kept a book of Ricordimemoriesas a way of documenting and pre From that book we learn that the young Machiavelli was sent to grammar school in 1476, where he learned some Latin as well as basic reading and writing in Tuscan. Then, in 1480, he learned the abacus, which is the way Florentines of the time referred to basic mathematics, of the sort that was appropriate to a merchant society, such as Florence in the fifteenth century. The year 1481 saw young Niccol placed under the tutelage of Paolo da Ronciglione, a teacher of Latin who, though little known today, counted a number of prominent Florentine intellectuals as his students.

In other words, Machiavelli had a solid early education, one that would have given him literacy as we know it: the basic ability to read and write ones own language. His education also made him, in the terms of his own era, litteratus, someone who had fluency in Latin. Latin mattered then, in ways that are difficult, if not impossible, to imagine today. For Machiavelli, as for those of his contemporaries who learned Latin, it provided a tool with which he could interpret the world as he experienced it.

The Latin language had died out as a native language (one spoken naturally in the home to children, say) centuries earlier, as it was transformed into what scholars term vulgar Latin after the fall of the Roman Empire: Latin, but in a register more attuned to the sentence structure and vocabulary of the emerging Romance languages of Italian, French, and Spanish. The first written documentation of something recognizable as Italian, as distinct from vulgar Latin, occurs only in the tenth century, in a manuscript preserving some legal formulas in southern Italy. Beautiful Italian poetry was written in the thirteenth century, as the poet Giacomo da Lentini penned works of courtly love at the southern Italian court of Frederick II, an admired ruler and cultural patron. Then, in the fourteenth century what Dante called his Commedia, or Comedy (later so admired that it came to be called the