Passage to Byzantium: The Romanov-Habsburg Feud that Led to World War I

Maggie Ledford Lawson

Pellissippi Press

Copyright 2019 by Maggie Ledford Lawson

All rights reserved.

Photographs and Other Credits:

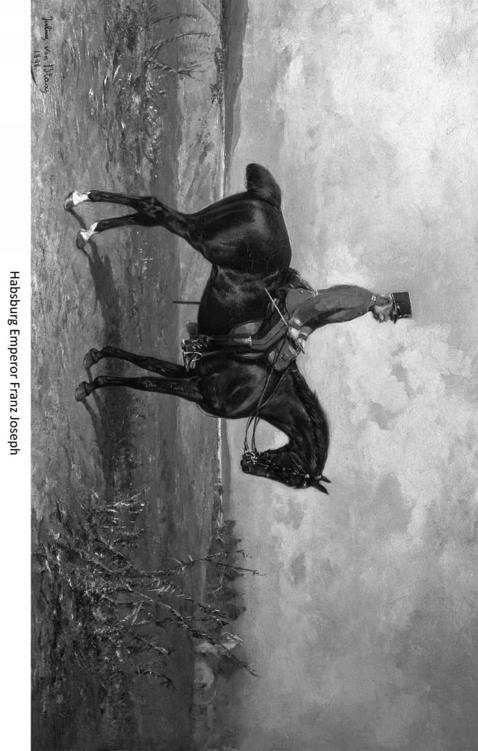

Emperor Franz Joseph I on his Austrian horse, 1898, Blaas, Julius von, (b.1845-1923) / Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria / Bridgeman Images, reprinted with permission

Portrait of Nicholas I of Russia (color litho), English School, (19th century) / Private Collection / Look and Learn / Bridgeman Images, reprinted with permission

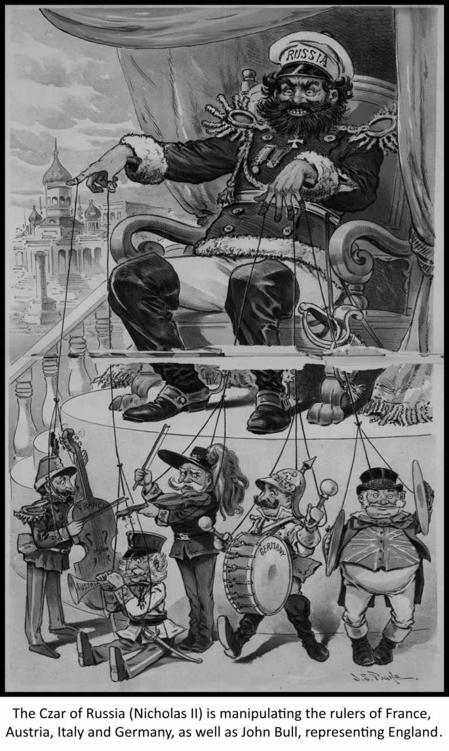

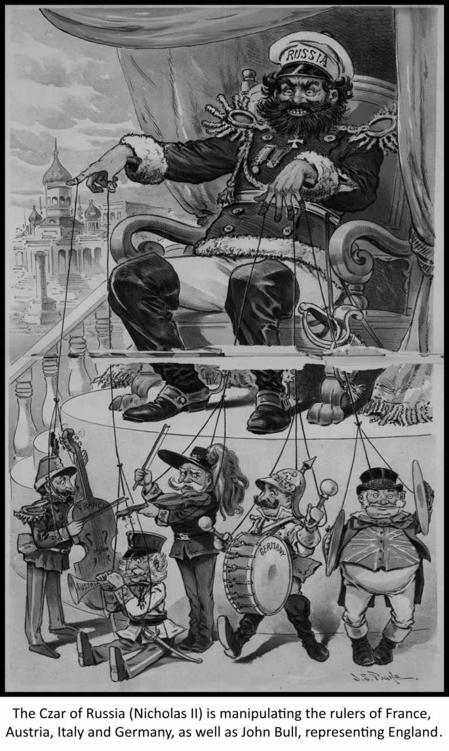

Cartoon: The European "concert," by J.S. Pughe, publ. 1897 / Library of Congress, no known restrictions on publication

Cover Design by R. St. James

Interior Design by K. Brice

ISBN: 978-0-578-57217-8

ISBN-13: 978-0-578-57217-8

DEDICATION

To Don Hill,

my late husband and best friend,

whose kindness, generosity

and patience brought joy to my life

and made this book possible.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank my many friends who have waited so long for me finally to have something to show for my years of research on this book.

I am particularly grateful to Archduke Markus Habsburg, the great-grandson of Emperor Franz Joseph, whom I met years ago during a visit to Bad Ischl, an Austrian spa town of historical significance as the site where the Emperor signed the papers that led to the Great War. The archduke has been a regular correspondent ever since, offering invaluable help in finding documents for my research and encouraging me to persevere in this project.

Among those who provided helpful suggestions for improving the text are Professor Robert M. Saunders, Professor Hugh Agnew, John Robbart and Margot Patterson. Additionally, I am lucky to have had excellent help in preparing the manuscript for publication. Pete Baumgartner offered expert assistance as a proofreader and wordsmith. Krysti Brice, with her eye for details and expertise in formatting, has been invaluable in creating the finished project. Ryan St. James has contributed his skill as a designer, providing the cover art and illustrations for the book.

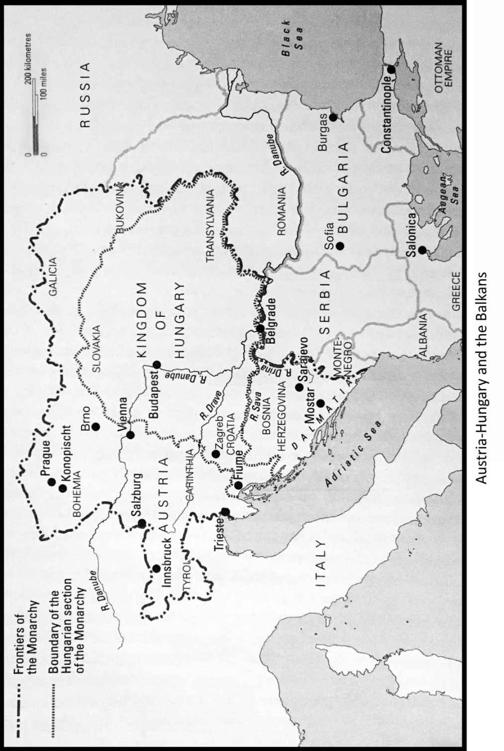

PHOTOGRAPHS AND MAPS

A NOTE ON USAGE

This book covers a large geographic territory that comprises many languages. Furthermore, the languages spoken by the persons and places named in this book are written in different alphabets (Latin and Cyrillic). Like all languages, they have changed over time both in terms of usage and spelling in the original language itself, as well as in English translations and transliterations.

The spellings of proper names and place names used here conform to current adaptations of each language into the English language.

INTRODUCTION

On April 28, 1919, two trains with some 200 German officials left Berlin for a Paris peace conference, marking the end of the First World War. Upon entering battle-ravaged areas of northern France, the trains slowed to a crawl in a French attempt to force the Germans to confront the devastation their army had caused. When the German delegates arrived at the Htel des Rservoirs in Versailles, they found that their baggage had been dumped in the hotel courtyard. The high-ranking dignitaries had to search for their suitcases and take them to their rooms. The drafty old hotel had no central heating and the weather was cold. The Germans were virtual prisoners in their hotel, which was surrounded by barbed wire and patrolled by sentries.

A week went by. Finally, Georges Clemenceau, the president of the peace conference, summoned the Germans to the Trianon Palace at Versailles to receive a treaty drawn up by the Western Allies. It was no accident that the French statesman chose the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles for this dramatic occasion. In that same room on January 18, 1871, Prussian King Wilhelm I had become Kaiser of a united German Empire, following a victory in an unprovoked war against France instigated by Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Germany had acquired the French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine at that time. Clemenceau intended to have his revenge.

While the Germans were of course aware that the French wanted to humiliate them, they persisted in the belief that they would be able to negotiate a just peace. On May 7, 1919, when the German plenipotentiaries stepped into the dazzling light of that famous room at Versailles, they arrived expecting to mount a defense against claims they were responsible for the Great War. They had reason to expect leniency. They hadnt started the war. They also had not surrendered unconditionally to the allies. Germany was now a republic. Kaiser Wilhelm II had gone into exile. The Germans had been led to believe that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson would see to it that they got a fair peace settlement.

The ailing American President, however, lacked the ability to persuade his allies to temper their judgment with mercy. Clemenceau and his supporters at the conference intended to see that the Germans were severely punished for what the Western leaders considered sins against humanity. There were to be no negotiations. The Germans, uniformly dressed in black morning coats, filed into the hall and took their seats facing their accusers. Clemenceau addressed the delegation in sonorous tones: Gentlemen, plenipotentiaries of the German Empire, this can be neither the time nor the place for superfluous words. The hour has struck for the weighty settlement of our accounts. He was to dictate the conditions of peace. I am compelled to add that the second Peace of Versailles (referring to the first peace in 1871) has been too dearly bought by the people represented here for us not to be unanimously resolved to secure by every means in our power all the legitimate satisfactions which are our due. The Germans were given 15 days to present their observations on the agreement in writing. They were being found guilty without a trial. This was a prescript for future war rather than a peace conference.

The German delegates, handed copies of the treaty, twisted nervously in their seats. The conditions of peace were harsh. The German army was to be reduced to hardly more than a police force. The Germans were to lose large swaths of territory in the countrys industrial areas. They were to forfeit their foreign colonies. Not surprisingly, Alsace and Lorraine were to return to the French. The Germans were to pay exorbitant reparations. Worst of all, in the eyes of many Germans, they were to acknowledge that they were solely responsible for the First World War. The German lead plenipotentiary, Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, a thin, sickly-looking man with a monocle, demanded to be heard. His request was granted. He remained seated as he spoke, apparently because he feared that his knees would give way. Many in the hall took his failure to stand as a sign of disrespect. His voice sounded like someone scratching on a blackboard. Acknowledging that having been vanquished the Germans expected to be punished, he went on to say that the demand is made that we shall acknowledge that we alone are guilty for having caused the war. His voice reached a rasping crescendo. Such a confession in my mouth would be a lie. He spoke for most of an hour, making a generally unfavorable impression on those present. The Germans, seeing no way out, signed the treaty. Clemenceau had exacted his revenge.