Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2012 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW

Copyright 2012 Stephen C. DeVito and Jack Womer

ISBN 978-1-61200-100-5

Digital edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-112-8

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

E-mail:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to

all American soldiers who served in World War II,

and the people they left behind.

They are not lost who fought and fell,

they only wait ahead.

Thomas Walbert, 29th Ranger Battalion

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J ack Neitz Womer, a kid from Dundalk, Maryland, was among the first of the millions of young American men who were drafted for World War II. Forced to leave his job with the Bethlehem Steel Company when called to serve his country in April 1941, Jack was drafted into the 29th Infantry Division, trained as an infantryman, and sent overseas in October of 1942. Always wanting to be the best soldier he could become, Jack volunteered for the 29th Ranger Battalion, a new and elite unit trained by British Commandos, and was among the relatively few men who met the extensive and rigorous requirements for becoming a Ranger. After the 29th Ranger Battalion was disbanded in October 1943, he volunteered to become a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division. His Commando training was viewed as at least the equivalent to the training the 101st Airborne Division had undertaken in Toccoa, Georgia, and made him eligible to become a Screaming Eagle. He earned his paratrooper wings by making the five required paratroop jumps within two days, instead of the usual seven.

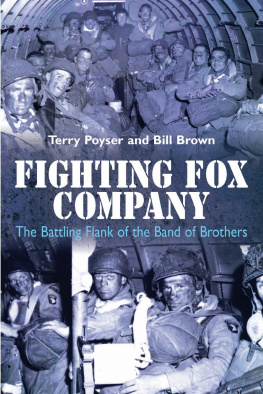

Jack was assigned to a special demolition section within the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne, known both famously and infamously as the Filthy Thirteen. It was with the Filthy Thirteen that he, along with the more than 6,000 other Screaming Eagles, was an active participant in the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the battle for Holland, and the defense of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge.

He witnessed firsthand the deaths of many soldiers, both Allied and enemy, as well as civilians, and the destruction and carnage brought about by war. Men who served with Jack will tell you that he was an exceptional soldier, served his country valiantly, and displayed unusually good leadership in combat. After the war Jack returned to his home in Maryland as a local hero. Like most returning veterans, Jack put the war behind him and picked up where he had left off before being drafted. He went back to his job in the steel mills, married his fiance, bought a house, raised two children, and eventually retired.

But all of the above occurred many years ago. World War II began and ended long before I was born. I had never heard of Jack Womer until one day in the early part of June 2003, when I noticed for sale on the internet an original photograph of some American soldiers training during World War II for invasion day, in reference to June 6th, 1944, the day Allied forces invaded France. The photo, shown on page 102, is of seven U.S. Army Rangers undergoing Commando instruction with model 1928A1 Thompson submachine guns. I've seen thousands of World War II photos, but few have intrigued me as much as this one. There was something about it that called out to me. I'm not sure what it was, precisely, but I believe it resides in the expressions on the faces of the soldiers and the circumstances in the photo: young men who just a few years prior had endured the hardships of the Great Depression of the 1930s and now, drawn together by destiny, seem proud and willing to defend the United States at great risk to themselves.

I was especially intrigued by the back of the photo, which had a caption listing the soldiers names and hometowns. The soldiers are identified as: Pfc John Toda of Sharon, Pennsylvania; Pvt. John Dorzi of Barrington, Rhode Island; Pfc Jack Womer of Dundalk, Maryland; Pfc Robert Reese of McKeesport, Pennsylvania; Lt. Eugene Dance of Beckley, West Virginia; Cpl. Dale Ford of Thurmont, Maryland; and Pfc Manuel Viera of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The caption was dated June 16th, 1943.

I purchased the photo and, coincidentally, received it in the mail on June 16th, 2003exactly sixty years to the day from the date in the caption. That evening my wife and two children went to the local theater to see a movie while I decided to stay at home and read. After a while I took a break and began looking closely at the photo, wondering about the men it depicted. Whatever happened to them? Did they take part in the Allied invasion of Normandy? Did they survive the invasion? Did they survive the war? Were they killed in action? Had they become close friends during the war, and perhaps lost touch with one another afterward? Do they or their families know of the photo? I thought to myself that if any of them are still alive, they would probably like to have a copy. For those that were deceased, I felt that it was important that their families have copies. I resolved to find out what happened to the men in the photo, and to provide them or at least their families with copies.

The only information that I had on each of the men was their name and their hometown. I began my search with two basic, although dubious, assumptions: 1) that each of the seven men survived the war and were still alive; and 2) each man returned to his hometown after the war and still lived there. I arbitrarily decided to start with the soldier whose hometown is closest to Chantilly, Virginia, where I live. I looked on a map and observed that Dundalk, Maryland, the hometown of Private Jack Womer, was closest, just over an hour's drive away. Using the internet White Pages, I searched for Womer, J in Dundalk, Maryland. No luck. I repeated the search for the state of Maryland and, among the Womers that appeared was a Womer, Jack living in Fort Howard, a small town adjacent to Dundalk.

The next day I set out to dial the number listed for Womer, Jack. Just before I dialed I became a little nervous since I didn't know what kind of a response to expect. I was concerned that whoever answered my call would immediately hang up after I explained why I was calling, and think that I was odd. I took a deep breath, dialed the number, and after a few rings the person who answered the phone shouted HELLO. A man had answered the phone, and from his pronunciation of this single word I suspected immediately that he was an older gentleman of the World War II era and an Army Ranger: the Jack Womer in the photo.

Hello, I said nervously, I'm looking for a Mr. Jack Womer. I'm Jack Womer, what do you want? shouted the voice on the phone. I have a photo, sir, taken during World War II. It's a picture of seven army Rangers holding Thompson submachine guns training in England for the invasion of Europe, and one of the men in the photo... Before I had completed the sentence the voice on the phone exclaimed That photo was taken in Scotland! It doesn't say Scotland in the caption, I responded. That photo was taken in Scotland! I was in the 29th Ranger Battalion, and that's where we trained, in Scotland. That's me in the photo, he replied excitedly. How are you so certain that this photo is of you, I replied. Look at my left hand, do you see a bandage on it? No, I don't, I responded. Look closer. I remember when that photo was taken, I had a bandage on my left hand, he said. I looked closer at the photo and, to my astonishment, in the photo the left hand of Jack Womer was indeed bandaged. I felt a chill run up my spine.

Next page