All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Ballantine and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Hal Leonard LLC for permission to reprint an excerpt from Can I Kick It words and music by Lou Reed, copyright 1990 by Oakfield Avenue Music Ltd. All rights administered by Sony Music Publishing (US) LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

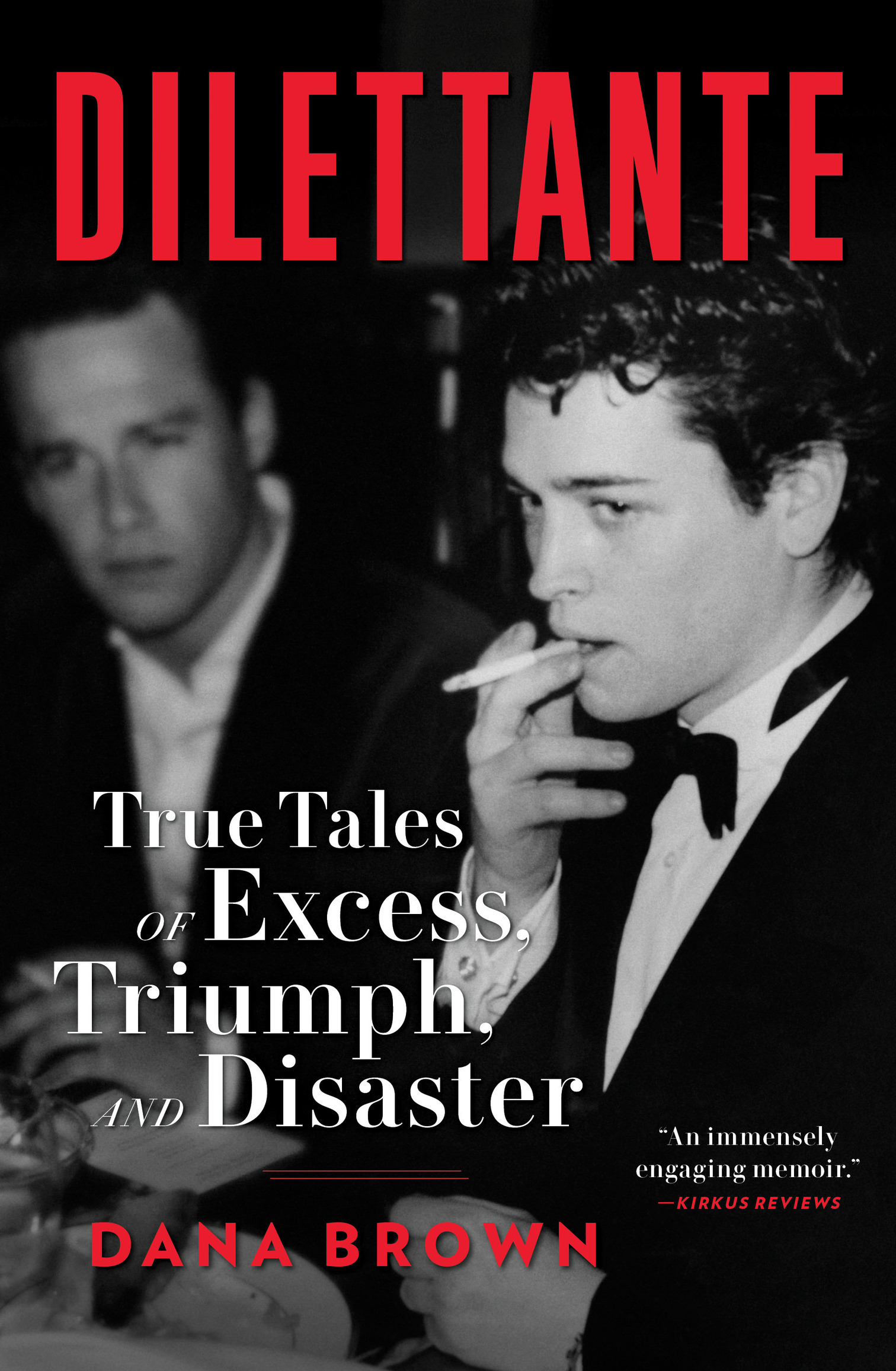

Introduction

Theres a tradition that originated in medieval times. When you turned twenty-one, you were given a key to the home. You were now considered old enough to take on the responsibility of being an adult and a senior member of the family. In some cultures, this tradition lives on. Nowadays, its mostly symbolic, a metaphoric key to your future, a key charm on a necklace or bracelet, maybe an antique key to carry around in a pocket or to sit on your desk. While I didnt recognize it at the time, on April 25, 1994, when I was twenty-one years old, I was given a key.

The key I received wasnt from a family member. It wasnt an actual key nor was it a symbolic keyit was a job. An entry-level job at a magazine. Not just any magazine, but one of the most popular, high-profile, successful, and culturally relevant magazines around, Vanity Fair, as an assistant to its editor, Graydon Carter. For the next twenty-five years, that key would unlock doors that would define my life, and the person I became.

At the time I was fairly aimless, a college dropout living in a fourth-floor walk-up railroad apartment in Manhattans grubby East Village: two bedrooms; lumpy futons on rickety loft beds, one for me and one for my twenty-five-year-old brother; $550 a month; mice; roaches; walls thinner than the junkies passed out in the buildings vestibule. There was a bodega on the ground floor that sold nothing but cocaine, its storefront window covered with faded yellow-and-red cans of Caf Bustelo. The coffee wasnt for sale, the cans simply there to obstruct the view of the stores interior, which was nothing more than barren shelves and a Dominican guy behind two-inch-thick bulletproof glass. The cocaine was low-grade stuff, cut with who knows what, but it worked in a pinch, if it was late and the decent stuff had run out.

The Hells Angels were my neighbors, just a few buildings east. The Angels had moved into the neighborhood in 1969, bought an old tenement building, and turned it into a clubhouse, making East Third Street between First and Second Avenues the safest block in Manhattan. Fifty years later theyd sell that building at 77 East Third Street for $10 million to a developer, the aging Angels having finally met a foe they couldnt vanquish with pipes, chains, and tire irons. Were being harassed by the yuppies down here, one Angel told the New York Post about the imminent sale. When the neighborhood was shit, nobody minded us. Gentrification is no victimless crime.

At the time, I had no future plans. I hadnt given a second of thought to a career. Working at a magazine was not something I aspired to or was equipped to do. But what began as an opportunity I couldnt refuse, something that I thought I might do for a year or twoif I made it that fareventually became my life, the halls of Cond Nasts building on Madison Avenue the beginning of my journey into adulthood and the start of a career that would continue for a quarter of a century. I learned a lot during that timeabout writing, journalism, culture, media, glamour, nostalgia, and maybe most important, the power of words and the importance of narrative.

I learned a lot about myself, too. Vanity Fair was the first institution I felt connected to, that accepted me for who I was. It provided me both an education and a surrogate family, with Graydon at the center of it all, as both my mentor and my guardian angel.

I bore witness to the power, vitality, and culture-shaping abilities of journalism and monthly magazines in what would turn out to be a golden age for the medium. We didnt just tell the story of our time, we played a part in driving the narrative for contemporary culture, celebrated its highs and shuddered at its lows. Some of what we did was frivolous. But a lot of it was important. Journalism was always considered a highly respected and vaunted industry, critical to society and democracy.

Language, and writing, is what separates us from our monkey ancestors. Its what makes us human, for better or worse. Stories, and narratives, have a way of taking hold and not letting go. Which is why the truth is so important. But narratives take hold whether theyre true or not. Journalism is our guardrail. Its our story, the official record of humanity. When its called into question, attacked, or practiced in bad faith, then the truth becomes subjective, and as a result, everything falls apart.

At Vanity Fair, we worked hard and took our role as a major responsibility. And when the hard work was done, we had fun. I might have had more fun than most. Who am I kidding. I was a fucking dilettante, a role I assumed and perfected. Ultimately, my identity and my career became intertwined into one tight weave, to the point that I couldnt tell where one began and the other ended. And if your job is creating a fantasy, a luxury itemand thats what we didits understandable why that would be appealing.

The story of the magazine business in the waning days of the twentieth century and the dawning of the twenty-first is also the story of New York, a place I have called home for most of my life and have developed a grumpy middle-aged revulsion to (while Im simultaneously willing to admit to a begrudging acceptance of its strange new traditions and culture). Its a city thats always attracted dreamers and misfits, artists and musicians, writers and weirdos, rich and poor, the aimless and ambitious alike, bound by the lore and lure of this place and the endless opportunities it presented. They were the fuel that made this place burn brightly for so many years. Inspired by the city, they gave us all that great art and poetry and journalism and literature and music, each generations work inspiring a younger crop of creative immigrants and natives alike, passed down like an older siblings book or record collection, who would take it, twist it into something new, something wonderful, from abstract expressionism to graffiti, from Rothko to Basquiat, from the beats to punk, from punk to hip-hop, which might just be the last great art form to emerge from New Yorks cultural cauldron, the end of the line.