LANCELOT BROWN and the CAPABILITY MEN

LANCELOT BROWN

and the

CAPABILITY MEN

Landscape Revolution in

Eighteenth-century England

DAVID BROWN and TOM WILLIAMSON

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright David Brown and Tom Williamson 2016

Supported by a Publications Grant from the

Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236926

CONTENTS

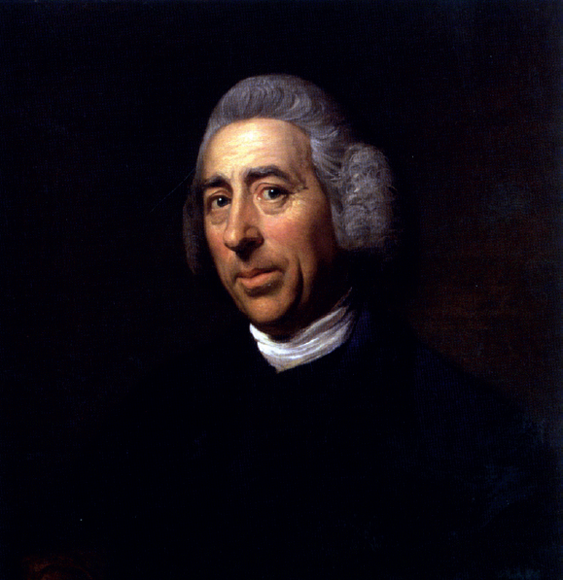

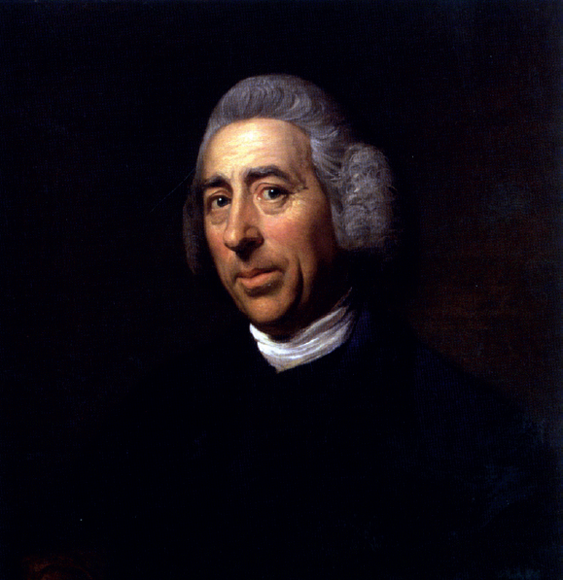

1 Lancelot Capability Brown, painted by Nathaniel Dance in 1773 at the height of Browns career.

ONE

The World of Mr Brown

L ANCELOT Capability Brown is the most famous landscape designer in English history, in part perhaps because of his memorable moniker, and the broad character of his creations will probably be familiar to most if not all readers (

Such acclaim has not been universal. Brown had many critics even while his career blossomed, and following his death his work came under more sustained attack from the Picturesque theorists Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight.

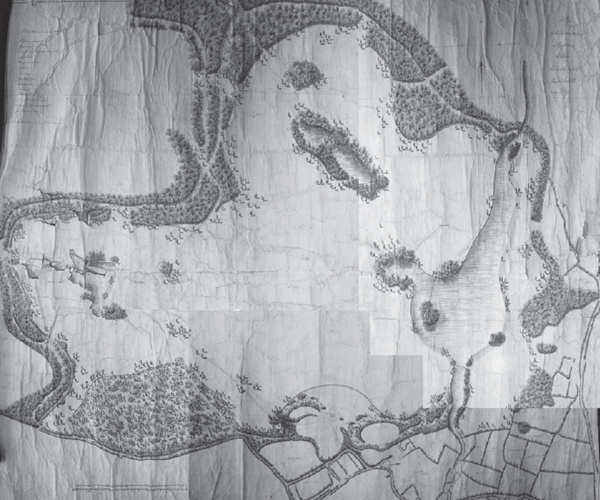

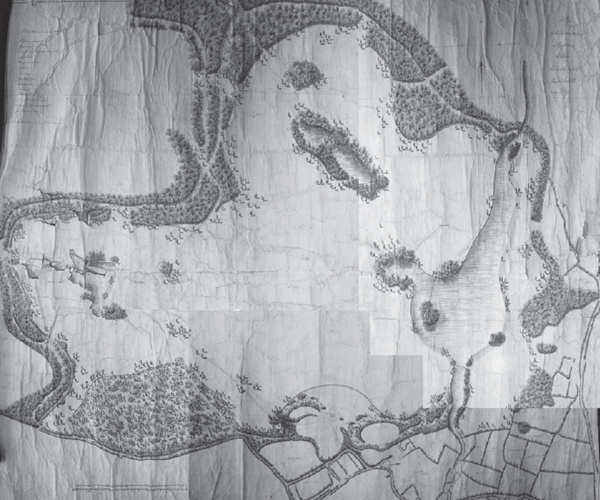

2 Browns plan for Wardour Castle, Wiltshire, made in 1773, shows most of the principal features of his style: sweeping expanses of turf, clumps, a lake and a perimeter plantation belt with circuit ride.

Brown was born in 1716 at Kirkhale in Northumberland, of modest although by no means impoverished parents. Modern scholars tend to exaggerate his lowly origins. In fact his father was a prosperous farmer, and his brother John married the daughter of the local squire, Sir William Lorraine, apparently without scandal or objection. Brown himself attended the local grammar school until he was sixteen, only then coming to work on Sir Williams estate, where he remained for seven years. The precise character of his employment there remains unclear, although it is likely that he was involved in and learnt much about estate management and forestry. In 1739 he left Northumberland and moved south, initially to Lincolnshire, and notably to Grimsthorpe, where he gained an important reputation as an engineer and became experienced in water management.

While still at Stowe Brown appears to have undertaken a number of commissions for other clients, principally friends or associates of Cobham himself, most notably the 6th Earl of Denbigh at Newnham Paddox in 1746 and Lord Guernsey at Packington in 1748.

Such a situation has allowed considerable speculation about the particular places where Brown may have worked. He has been identified as the designer of around 267 houses, gardens or landscapes by one authority or another, but suspicion surrounds many of these attributions:

3 Ditchingham in Norfolk, although often claimed as a Brown park, was almost certainly laid out by some other designer around 1765. The vast majority of landscape parks in eighteenth-century England were created by one of Browns so-called imitators.

And it is the role of such men, and their relationship with Brown himself, that are among the main topics ad dressed in this volume.

Although we still have much to learn about Capability Brown and the eighteenth-century landscape park, a great deal has been achieved by both professional and amateur researchers over the last few decades. In addition to the volumes noted above, important new light has been cast on Brown himself by John Phibbs in a series of scholarly and sometimes provocative articles. This book draws extensively on all this work. But it is also the outcome of our own researches, carried out over many years, into various aspects of Browns career, and into the development of eighteenth-century landscapes more generally. In particular, an extensive analysis of contemporary bank accounts not just those of Brown, but of a broad section of wealthy individuals allows us to understand rather better the working methods of someone who, whatever his claims to artistic genius, was above all a consummate businessman.

In this Brown was very much a product of his age, and fundamental to this book is the idea that the landscape park cannot be understood simply as the product of a single artist. In part this is because it is no longer clear that the landscape style was indeed invented or pioneered by Brown himself: it was, as we shall argue, simply the style of the times, and Browns imitators were no more and no less than colleagues or rivals in the business of landscape design. In part, however, it is because the landscape styles success indicates that it met a number of pressing contemporary needs, fitted in well with the aspirations and lifestyles of wealthy consumers. To understand the landscapes created by Brown we must therefore begin with a brief account, no more than a thumbnail sketch, of some of the key characteristics of eighteenth-century England. Some of this may seem to take us far from the world of gardens and landscapes, but landscape design was a serious business in the eighteenth century, and cannot be understood in isolation from the wider world or from politics, economics and social relations. Those seeking to learn more about Browns place-making will have to be patient: the character of this wider world needs first to be briefly, all too briefly, presented.

Politics

We will begin with politics and ideology, for styles of garden design in eighteenth-century England, together with styles of architecture, have often been explained as expressions of particular political ideologies, or as representations of the political system more generally.political opponents of corruption. But politics in the eighteenth century was not entirely devoid of genuine ideological debates, and for most of the eighteenth century these were usually described in terms of a clash between Whigs and Tories.

The Whigs originated as the faction that had successfully opposed the succession to the throne of James, Duke of York and brother of Charles II, in the Exclusion Crisis of 1679; the Tories, as the group who had supported him, and they continued to be supporters of the Stuart succession throughout the rest of the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth. But there were other differences between the two groups, which became more prominent in the eighteenth century. In particular, the Whigs believed in a measure of religious toleration and became increasingly opposed to involvement in the wars which wracked continental Europe (largely because they raised levels of taxation), yet at the same time were keen on a foreign policy directed towards the promotion of trade. They were the party, in essence, of the social groups who had benefited most from the Civil War: great aristocratic families like the Cokes or the Townshends, the city interests of financiers and merchants. The Tories were in many ways a more diffuse group, but while led by major aristocrats like the Earl of Bolingbroke they drew much of their support from the countryside, from minor rural gentry. They were the party of the established Church, suspicious of increased religious toleration, initially at least supporters of the Stuart succession and widely suspected (in some cases, not without justification) of harbouring residual Catholic sympathies. But they were not simply a party of backwoods squires opposed to the erupting world of commerce. One of their key members in the first decades of the century, Robert Harley, was among the founders of the South Sea Company, the dubious joint-stock venture that collapsed, spectacularly, in 1720. Nor were all minor country landowners supporters of the Tory cause, not least because as explained below this could bring serious personal and financial difficulties for much of the eighteenth century. While this description of the two groups is probably useful in very general terms, it masks a shifting pattern of aristocratic allegiances, and the meanings of the two terms were elaborated and redefined as the eighteenth century progressed.