There is a memorable scene in Charlie Chaplins classic Modern Times in which the Little Tramp picks up a red warning flag that has fallen from the back of a delivery truck. As he is waving the flag and shouting to get the attention of the driver, a noisy mob wheels around the corner behind him and he finds himself, more or less innocently, in the vanguard of a revolutionary movement. This is not so far from our feeling as we look back at all that has transpired in the decade since the initial publication of Change by Design. We did not invent design thinkingthat honor is the subject of an academic cottage industrybut its fair to say that we were in the right place at the right time. When we looked back over our shoulder, we discovered that there was a revolutionary movement behind us.

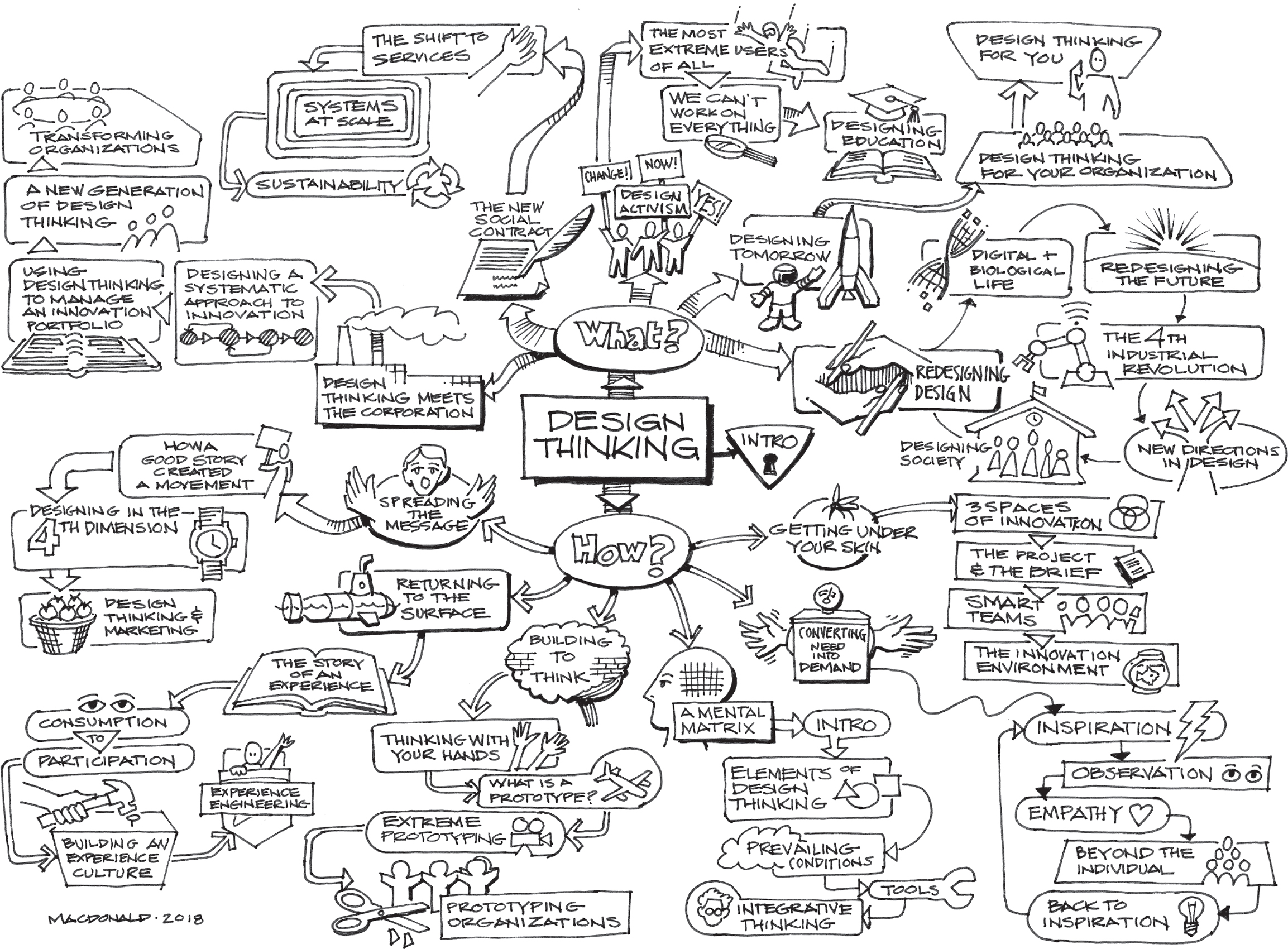

Put simply, Change by Design set out to make two points. First, design thinking expands the canvas for design to address the challenges facing business and society; it shows how a human-centered, creative problem-solving approach offers the promise of new, more effective solutions. Second, design thinking reaches beyond the hard skills of the professional trained designer and should be available to anyone who wishes to master its mind-sets and methods. Our common interestdesigners and design thinkerslies in finding better answers to the challenges that confront us all. A decade after first sharing these ideas, I am more convinced than ever of their relevance to the contemporary world.

Our journey at IDEO has continued to be one of constant discovery as we are challenged to tackle problems that are both broader and deeper than ever before. Since Change by Design was first published, we have been asked to apply design thinking to educational reform in Latin America; to departments of government in the United States, the Middle East, and Asia; to a succession of new social organizations providing services in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia; to start-ups worldwide employing the latest digital, robotic, and biological technologies.

Even more remarkable, the cluster of approaches we call design thinking has been embraced by businesses, social organizations, and academic institutions in every part of the world. Hundreds of thousands of students have been introduced to its basic concepts through classes at business schools and engineering schools or through online courses and freely available tool kits. These design thinking graduates are now practicing their skills at the level of inspiration, ideation, and implementation. Each of them is creating impact, large and small.

The evidence of impact is indeed emerging. Some of the worlds most influential technology companiesApple, Alphabet, IBM, SAPhave moved design to the very heart of their operations. SAP has used design thinking to launch billion-dollar products in record time while funding design thinking education worldwide. IBM has integrated design thinking into its products and services and evolved the practice to focus on its enterprise customers, hiring hundreds of designers in the process. Designers are part of the founding teams of disruptive start-ups across Silicon Valley and around the world. Health care systems, financial services firms, and management consultancies now regularly employ designers, while teachers are bringing design thinking to kindergarten classes, senior high school courses, and everything in between. The methods of the designer, as my friend Roger Martin has shown, have even been embraced by the military. Design thinking has truly come of age.

And yet we should not rush to congratulate ourselves, for we are still at the beginning, and we are rightly asked what it takes for design thinking to truly have significant impact.

A first question we must ask relates to the topic of mastery. As you proceed through Change by Design you will discover that design thinking includes a great many methods and skills, and as with any skill, there is a difference between the performance of a neophyte and that of a master with thousands of hours of practice. Similarly, rookie teams, even if they contain one or two masters, rarely outperform teams who have developed trust and understanding through previous projects. While technology can do much to accelerate learning and amplify impact, there is no real substitute for mastery. That mastery entails gaining what my colleagues Jane Fulton Suri and Michael Hendrix call design sensibilities. As they wrote in Rotman Management magazine, design sensibilities consist of the ability to tap into intuitive qualities such as delight, beauty, personal meaning and cultural resonance. Being intuitive in the application of design leads to more relevant experiences that connect emotionally to people and gain greater loyalty from customers. Until we have trained a critical mass of design thinking masters, we will surely be falling short of what might be achieved by the application of design thinking to the worlds most challenging problems. Hence, I would encourage you not to be satisfied with merely understanding and applying the concepts of design thinking but instead to find your own path to mastery. If my own experience is any guide, such a commitment can provide a lifetimes worth of creative satisfaction.

A second question relates to ethics. Increasingly we face a technology backlash as the business models of social media, artificial intelligence, and the Internet reveal their dark side. On the one hand, human-centered design can be applied as an antidote to the cold dominance of technology and its inherent bias to replace or devalue the contributions of people. On the other hand, there is abundant evidence that design is being used to seduce us to the addictions of social media, artificially intelligent services, mobile games, and other technological enticements laid before us. Design thinking is not the invisible hand. It is intentional. As Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon stated in his 1969 treatise The Sciences of the Artificial, Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. If we design social media applications to be enticing and addictive, then we are doing so because we wish for that outcome. If we dont wish what we get, then we are being very poor designers. Design thinkers have a responsibility to understand the outcomes they are designing for and to be conscious about the choices they are making. We are at a critical moment in the evolution of technology where we can see its potential to supersede human intelligence. This is a moment for the visible hand of design to make intentional choices about how we wish technology to serve humanity.

The final question relates to application: What are the problems to which we should be directing our energies? Designing for human-centered artificial intelligence is certainly one, but, in general, I would suggest that too much of our effort has been focused on the incremental and not enough toward truly groundbreaking ideasand I dont mean groundbreaking only in the Silicon Valley sense of new products or new technology. As we dive deeper into the twenty-first century, it becomes clearer that the majority of our societal systems are no longer fit for purpose. They were designed to meet the requirements of the first machine age and have remained essentially unchanged since the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

What might be the impact if we can successfully apply our design thinking skills to the truly wicked problems of the twenty-first century? How might we design organizations, education, civic engagement, industrial systems, markets, health care, transportation, taxation, faith, work, and communities both physical and virtual, to be fit for ourselves, our children, and our grandchildren? These, I would argue, are worthy challenges for the design thinker.