This book is dedicated to my husband Michael, our daughter Gabrielle and her husband Peter Gaunt, and our granddaughter Emily

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CURRENCY

According to www.measuringworth.com

In 1750 the value of a 100 0s 0d Commodity compares to 2014:

the real price of that commodity is 14,050.00;

labour value of that commodity is 178,100.00;

income value of that commodity is 278,200.00.

In 1750 the value of 100 0s 0d of Income or Wealth compares to 2014:

the historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is 14,050.00;

economic status value of that income or wealth is 278,200.00;

economic power value of that income or wealth is 1,638,000.00.

In 1750 the value of a 100 0s 0d Project compares to 2014:

the historic opportunity cost of that project is 13,920.00;

labour cost of that project is 178,100.00;

economic cost of that project is 1,638,000.00.

Between 1750 and 2013, prices rose by around 145 times. References to money in the script will be followed by an equivalent amount based on these statistics; for example, a very good bottle of claret that cost 6 shillings in 1750 would cost in the region of 42 today.

| Pound sterling (silver) | = 20 shillings | = 240 pennies | = 480 hapennies | = 960 farthings |

| Shilling (silver) | = 12 pennies | = 24 hapennies | = 48 farthings |

| Groat (silver) | = 4 pennies | = 8 hapennies | = 16 farthings |

| Penny (copper) | = 2 hapennies | = 4 farthings |

| Hapenny copper) | = 2 farthings |

| Farthing (brass) |

| Guinea (gold) (after 1707) | = 21 shillings |

| Crown (silver) | = 5 shillings |

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY MEASUREMENT

Length was measured as follows:

| Inch | 2.54 centimetres |

| Foot | 30.48 centimetres |

| Mile | 1.6 kilometres |

| Span | 22.86 centimetres |

| Cubit | 0.46 metres |

| Hand | 10.16 centimetres |

| Furlong (220 yards) | 201.16 metres |

| Palm | 7.5 centimetres |

| Rod (16.5 feet) | 5.03 metres |

| Chain (22 yards) | 20.12 metres |

| League (approx. 3 miles) | 4.8 kilometres |

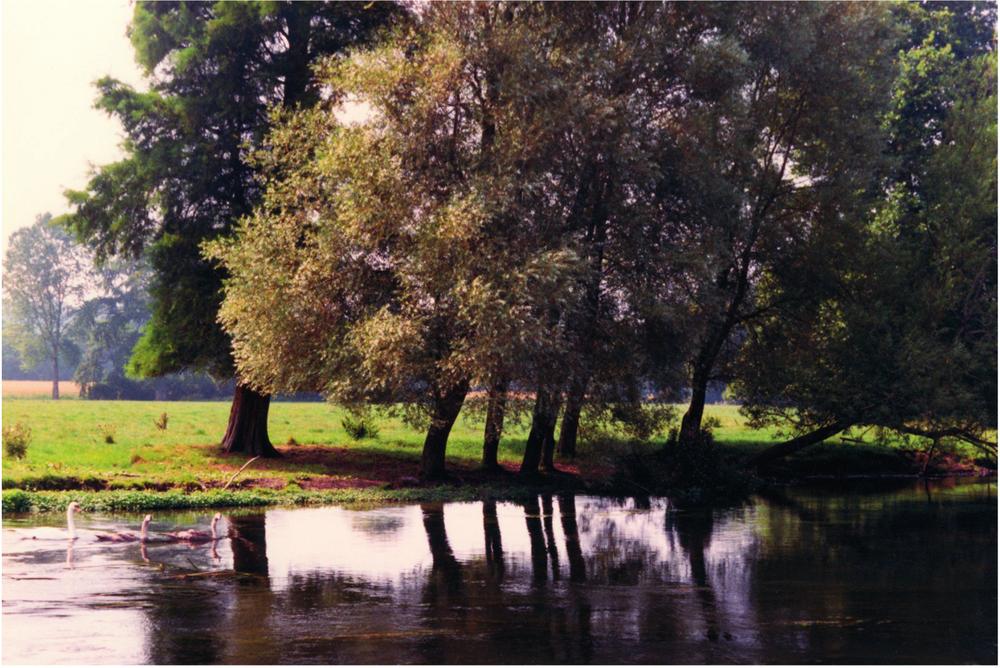

(page 1)August 1981, Broadlands, Hampshire A scene along the River Test that misled me into thinking it was natural countryside. I later learned that Capability Brown had designed the setting. The exotic swamp cypress (left) and grove of native white willows (right) are typical of his planting.

(pages 2 and 3)October 1989, The Pastures, Alnwick, Northumberland A seemingly natural view from Alnwick Castles Pic-Nic Tower. Brown altered the course of the River Aln and transformed unkempt, craggy moorland into grazing grounds. Alnwick townsfolk have always been free to walk here; many believe it has always been like this.

NOTE: in captions, NT is National Trust; EH is English Heritage; HE is Historic England.

A star or arrow, superimposed on certain plans, highlights particular design features.

All images by the author unless credited otherwise, including images of National Trust properties with permission.

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER ONE

NORTHUMBERLAND - CHAPTER TWO

MR BROWN ENGINEER - CHAPTER THREE

THE FINEST GARDEN - CHAPTER FOUR

CLIENTS, SURVEYS & PROPOSALS - CHAPTER FIVE

CONTRACTS & ASSOCIATES - CHAPTER SIX

GROUNDWORK - CHAPTER SEVEN

LAKE-MAKING - CHAPTER EIGHT

RIVERS REAL & ILLUSORY - CHAPTER NINE

CASCADES - CHAPTER TEN

PROBLEMS & PUMPS - CHAPTER ELEVEN

ROYAL GARDENER AT HAMPTON COURT - CHAPTER TWELVE

PAINTS AS HE PLANTS - CHAPTER THIRTEEN

NOW THERE I MAKE A COMMA - CHAPTER FOURTEEN

SHRUBBERY SWEETS & FLOWER GARDENS - CHAPTER FIFTEEN

COMFORTS & CONVENIENCE - CHAPTER SIXTEEN

FREEDOM TO ROAM - CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

KEEP ALL IN VIEW VERY NEAT - CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

MOVING HEAVEN - CHAPTER NINETEEN

THE KITCHING GARDEN - CHAPTER TWENTY

FULL-SCALE DRAMA - CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

ADVERSITY OF MAN & NATURE - CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

TRANSITION - CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

THE MYSTERY OF THE GARDEN - CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

LOVE OF COUNTRY - CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

EPILOGUE: STILL CAPABLE

People will not look forward to posterity who never look backward to their ancestors.

EDMUND BURKE

E veryone has landscapes lodged in their memories, many from childhood.

I remember my first real urge to take a photograph. I was eight years old, visiting the Dutch tulip fields of Keukenhof. Such glorious settings have the power to evoke deep emotions or, simply, take the breath away. Whatever the view, we all see things differently from each other. We see with memory.

My father once told me he found it difficult to appreciate landscape. Such was his training as a gunner in WWII that any time he surveyed a beautiful scene, sadly, his eyes saw only possible gun emplacements. His compensation was that he delighted in writing verse, and would read to me from this memory bank, or snippets of his favourite poets, especially Robert Frost. Some lines have never left me.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I

I took the one less travelled by,

And that has made all the difference.

My different journey began in Hampshire, at Broadlands. I ignored the classical charm of the house as a sweeping lawn led me down to the edge of the meandering River Test. A pair of swans piloted their cygnets under leaning white willows. A spreading copper beech attracted attention at the river bend, great trees punctuated the water meadow, and upstream a stand of Scots pines dominated the river bank. All seemed serene, reassuring. Nothing disturbed the eye or the peace.

I fell under the spell of the place, and later discovered that this pastoral setting had been to a great extent man-made by the celebrated Capability Brown.

Five years passed. I had given up teaching to bring up a family, and taken up garden photography, a passion kindled by two years of living in California sunshine and later properly stoked by the trail-blazing photography of Andrew Lawson.

My husband, an officer in the Royal Air Force, was posted to a radar station on the east coast of Northumberland, and we moved there with our young daughter. In October 1987, as I dashed to catch my train to Newcastle, the great hurricane devastated vast tracts of land in the south of the country, and uprooted millions of trees, a loss that greatly affected me it was almost as bad as losing ones friends.