CONTENTS

Christophe Girot and Dora Imhof

Vittoria Di Palma

Saskia Sassen

Emily Eliza Scott

Susann Ahn and Regine Keller

Sonja Dmpelmann

Charles Waldheim

Jrg Rekittke

James Corner

Christophe Girot

Kathryn Gustafson

Kongjian Yu

Kristina Hill

David Leatherbarrow

Alessandra Ponte

Anette Freytag

Stanislaus Fung

Adriaan Geuze

INTRODUCTION

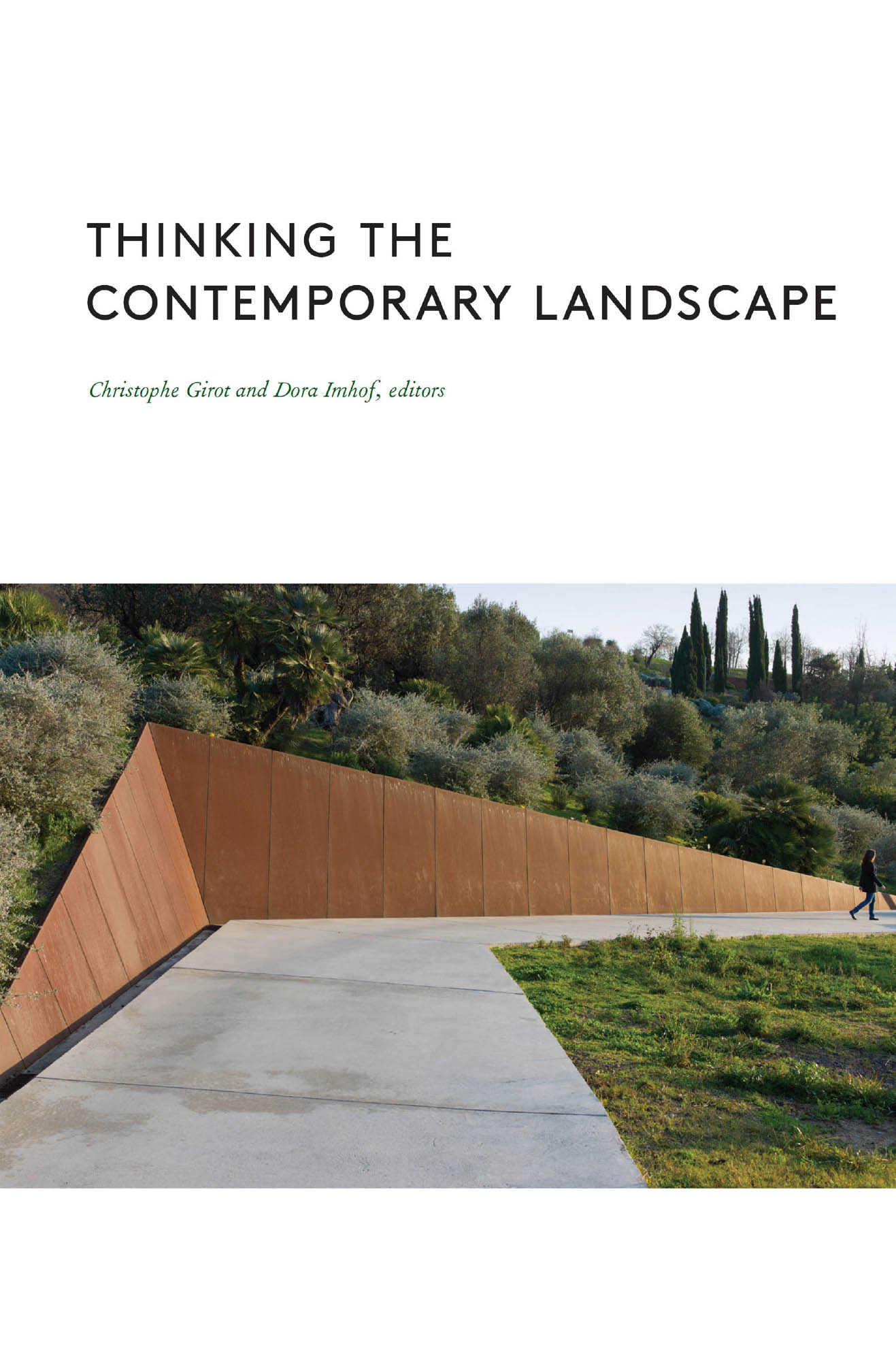

Thinking the Contemporary Landscape is a compilation of essays that look at the profession of landscape architecture as it reacts to new challenges posed by both societal and environmental change and considers new fields of action. Landscape architecture suffers from broad intellectual dispersion and tremendous cultural disparity, precisely at a moment when direction and cohesion are indispensable to our civilization. Our editorial line seeks to identify aesthetic concerns that, recently, have all too often been overshadowed by a positivistic scientific discourse about nature. This seventeen-essay collection aims to contrast the current discourse with a more philosophical and poetic stance. It pinpoints a contemporary form of intelligence about landscape by relating positions from outstanding academic thinkers and practitioners. Most of the authors took part in a symposium that was organized in 2013, with generous support from the Volkswagen Foundation, at Herrenhausen Palace in Hanover, Germany. Additional authors were solicited thereafter, to complement certain facets of a contemporary debate on representation and politics that we found to be lacking at the symposium. This book reflects on current thinking in landscape architecture and is meant to open the discussion and nurture further inquiry into design methods and aesthetics.

Landscape is a cultural artifacta construct resulting from the belabored shaping of terrain and the making of place; it has, in fact, very little to do with the ideal of an untouched wilderness. This plain definition of the word as the product of successive stages of human culture enables us to frame a discussion about symbolic expression and form giving within the realm of the politics of space. What actually constitutes the proper immanence of a landscape in our age? What role does memory play in this reading of place? How does one identify concretely the contemporary aesthetic and intelligence of a given landscape, particularly through the virtual realm? At a moment of relentless conceptual oscillation and environmental uncertainty, the timeless quality of a landscape is strikingly frail, idealistic, almost idiosyncraticit has neither the solidity nor the proper physical resilience to resist the centrifugal thrust of our age.

The juxtaposition of science and memory, of exponential development and history, points to one of the major contradictions in contemporary landscape thinking, which mirrors a multitude of heterogeneous and often conflicting ideologies that attempt to define a world that is constantly being reshaped and reinterpreted by newer forces. As a result, there exists a schism between the way a landscape is understood scientifically and the way it exists cognitively, mnemonically, and emotionally for people. This mix of rational scientific discourse and poetic interpretation about landscape has never been so murky and inextricable as it is today. The authors were asked to take issue on a variety of subjects in which the topic was either reframed, recomposed, or rethought, to see whether a dialogue could even occur between the individual experience of secular myths of landscape on the one hand, and scientific positivism on the other. Some authors were asked to reflect on the relevance of science and memory in relation to aesthetics; others were asked to comment rather on the expression of power on the terrain. A discussion about heuristic and empirical methods was intended to shed light on differing, yet sometimes complementary, approaches to landscape design. Is it actually possible to reconcile science and memory in our present culture? Paying critical attention to the way we conceive our environment, both symbolically and scientifically, may indeed help restitute a stronger vision and direction in landscape architecture.

This book is organized into three parts. However, these sections should not be seen as completely autonomous from one another; there are indeed many thematic correspondences between them.

Part one addresses the societal and epistemological shifts that have occurred in our conception of nature and perception of place. Effects of climate change, combined with a rapid increase in population growth and neoliberal globalization, provide an incentive to rethink nature and landscape in many disciplines. The popularization of the concept of the Anthropocene by the atmospheric chemist Paul J. Crutzen and the biologist Eugene F. Stoermer in 2000 has brought us to question not only domains pertaining to nature, such as landscape architecture, geology, and geography, but also art production and art history, philosophy, and sociology. While the ecological debate has been ongoing for several decades now, a broader theoretical interest in landscape theory has been rekindled by a wider discourse on nature and its recent history.

The first part of the book, with essays by Vittoria Di Palma, Saskia Sassen, Emily Scott, Sonja Dmpelmann, and Charles Waldheim, focuses on the concept of wastelands, which is central to the transformation of urban areas. It is not so much with some idyllic landscapes, but rather through the mirror of contested, ) Conflicting ideas about what is actually possible and desirable in a landscape and how the field of action narrows down for given interventions become all the more apparent in the essays of Susann Ahn, Regine Keller, and Jrg Rekittke.

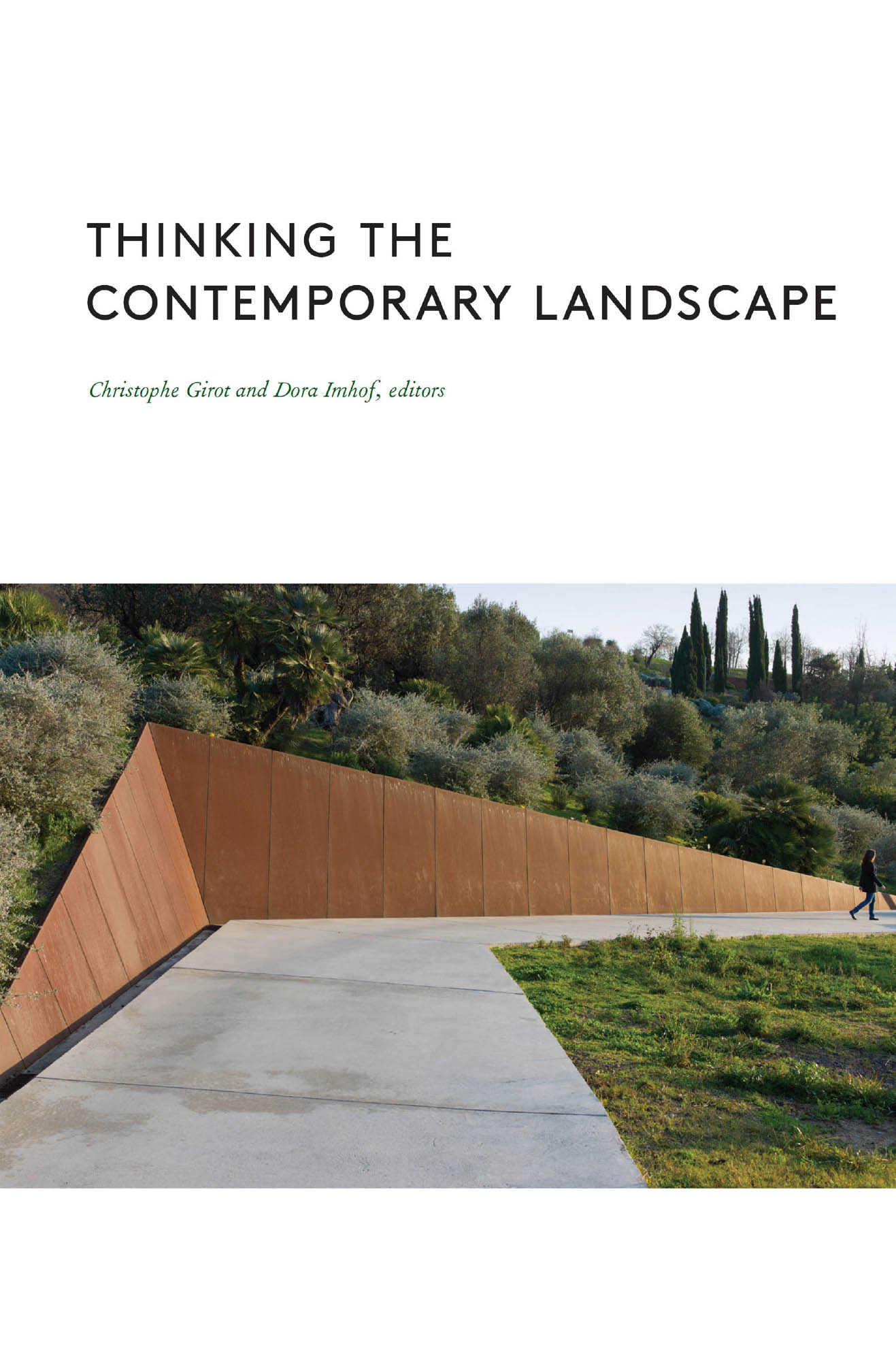

FIG. 1 Suburb of Toledo, Spain, 2007.

FIG. 2 Imperial Wharf, Chelsea, London, 2008.

FIG. 3 Central Business District, Montreal, Canada, 2009.

All photos by Christophe Girot.

Part two explores different methods of design with an international perspective, focusing on Europe, China, and the United States. Over the past century there has been a tendency to reduce the field of action of landscape design both pragmatically and scientifically. Large-scale landscape analysis has in part taken over the realm of design, through engineering and with the help of elaborate mapping overlay techniques that selectively arrange layers of information pertaining to a site with no particular regard to a landscapes given physical, historic, and aesthetic qualities. This empirical fragmentation, in which landscape is treated repeatedly in separate divisions, has created a highly abstract, scientific vision of terrain that is quite removed from any reality of place. In turn, such a highly reductive and deductive approach to design, combined with strong eidetic evocations, has enabled the global transfer of an idealized brand of landscape mapping, as a substitute for design without any specific consideration for cultural appropriateness and specificity.

Next page