First published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

All rights reserved.

The right of Barry Hatton to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Carmo, who makes things possible.

A culture, we all know, is made by its cities.

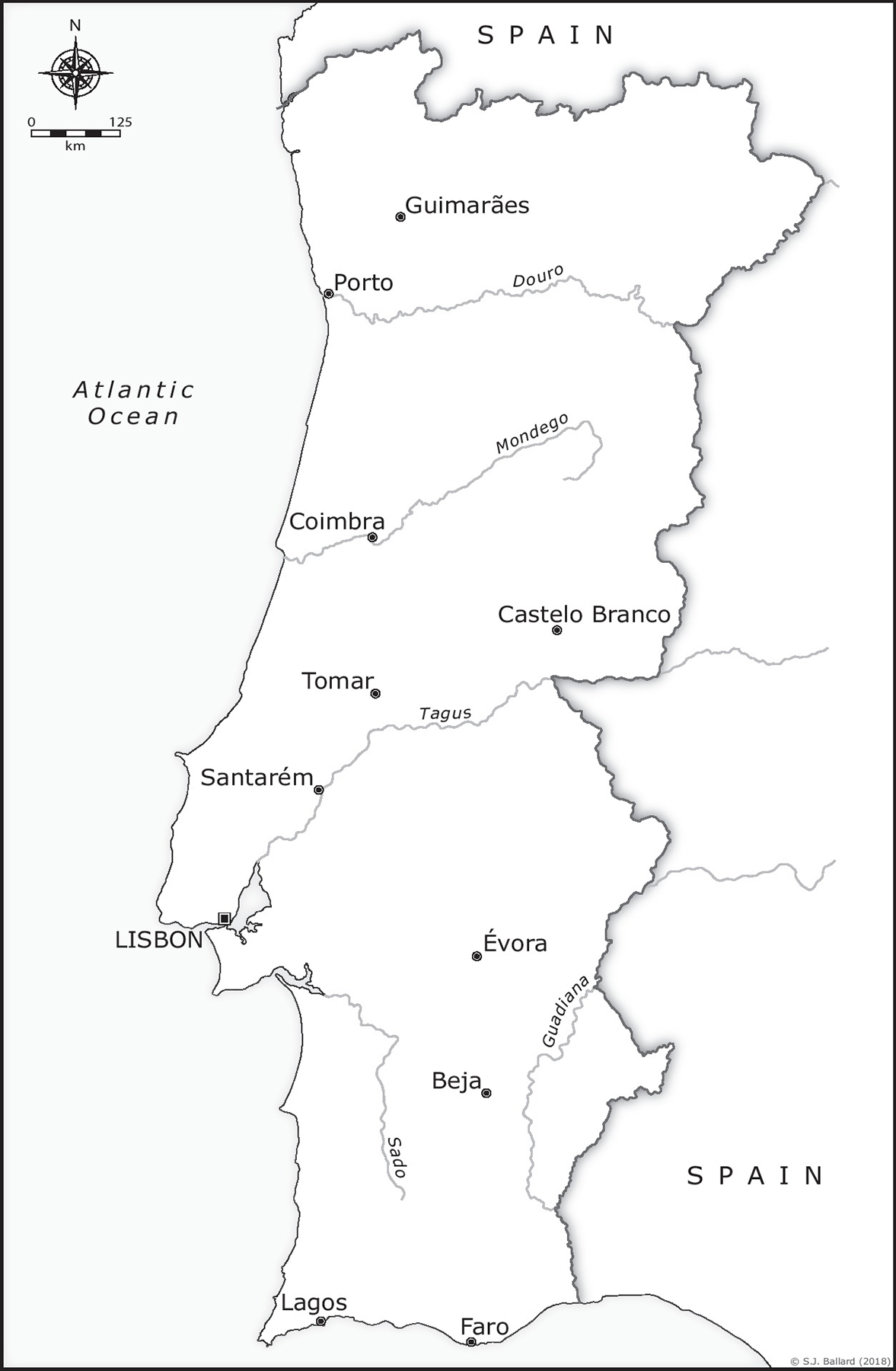

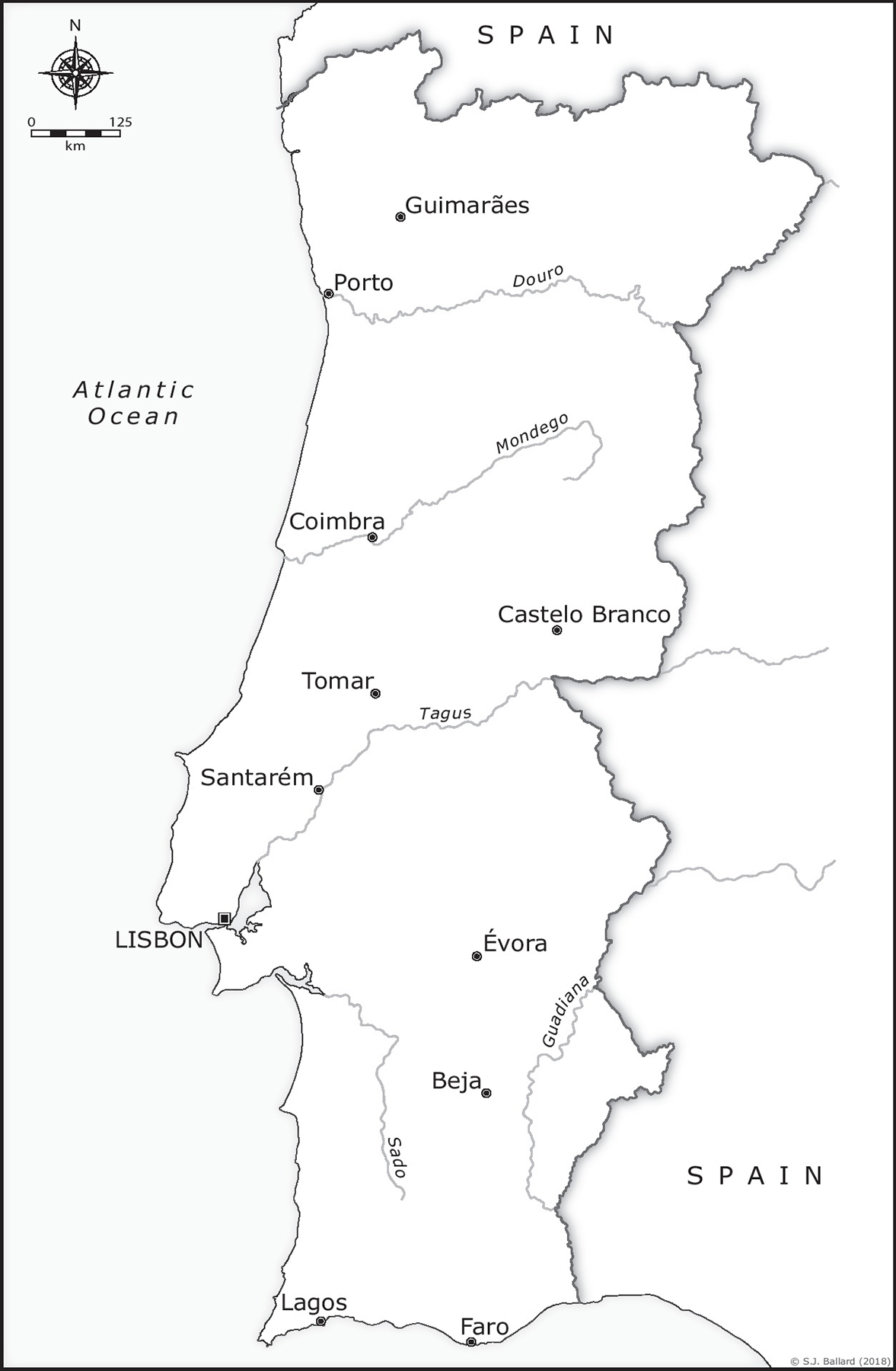

Map of Portugal

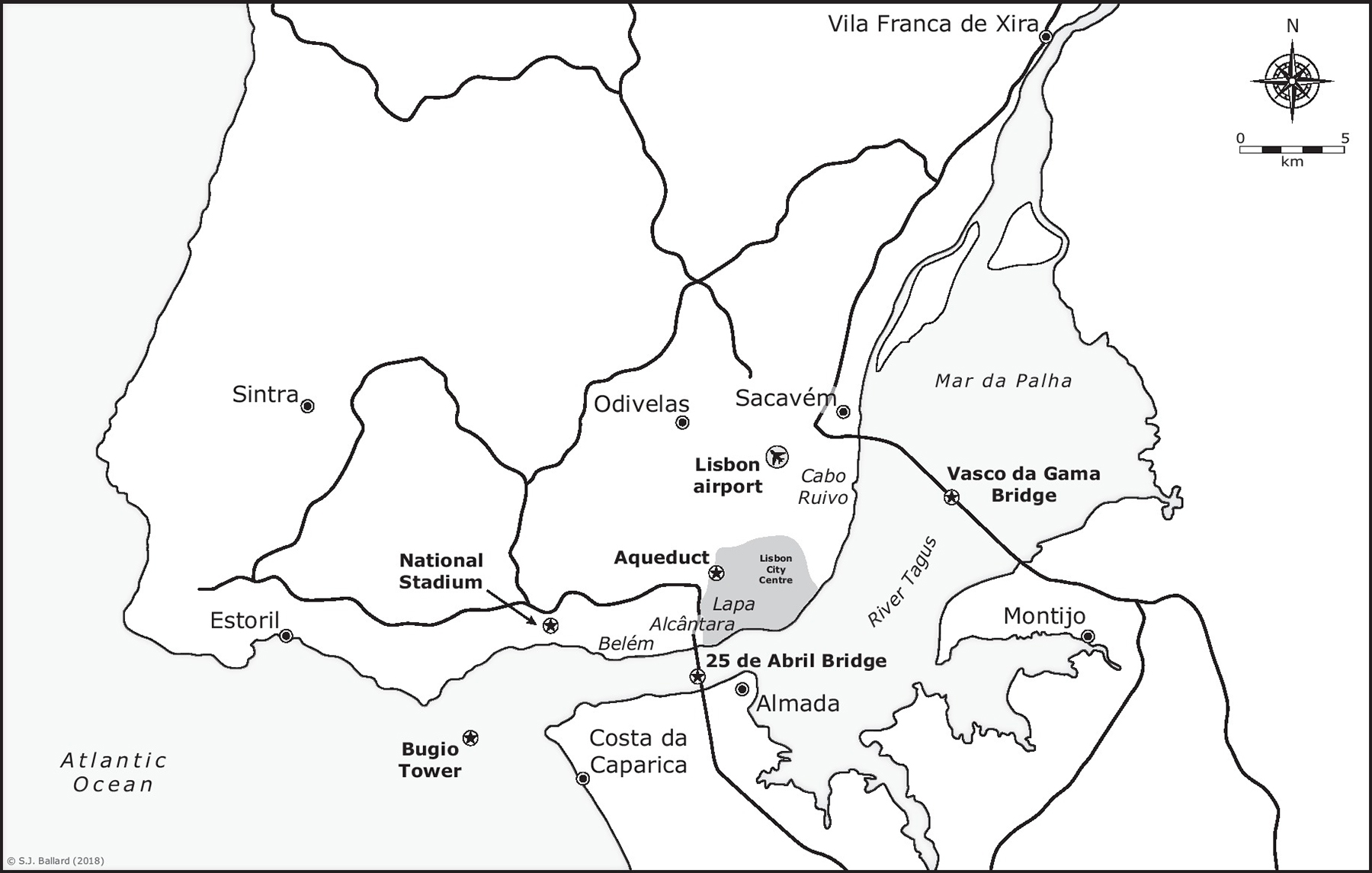

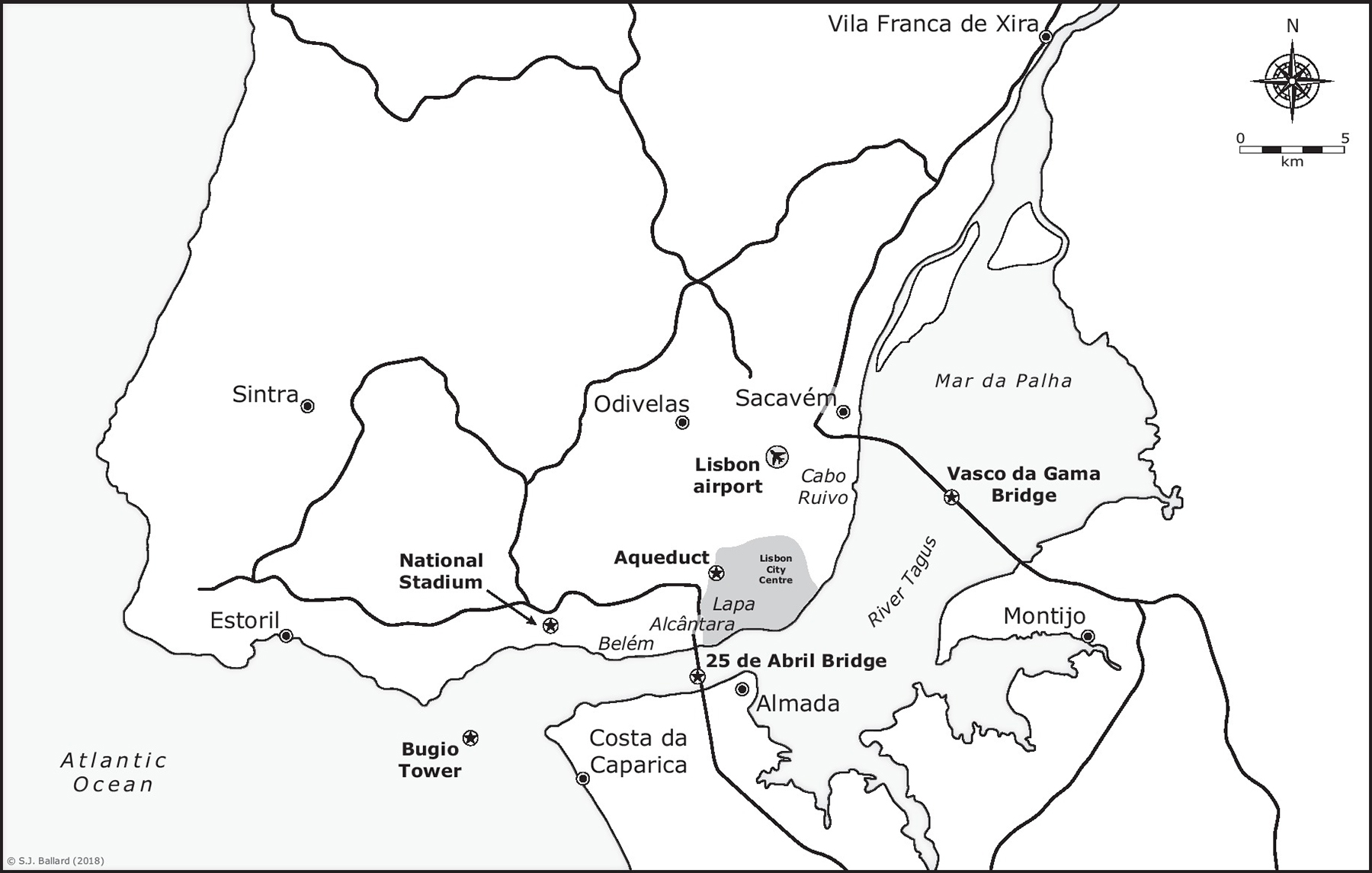

Map of the Lisbon Region

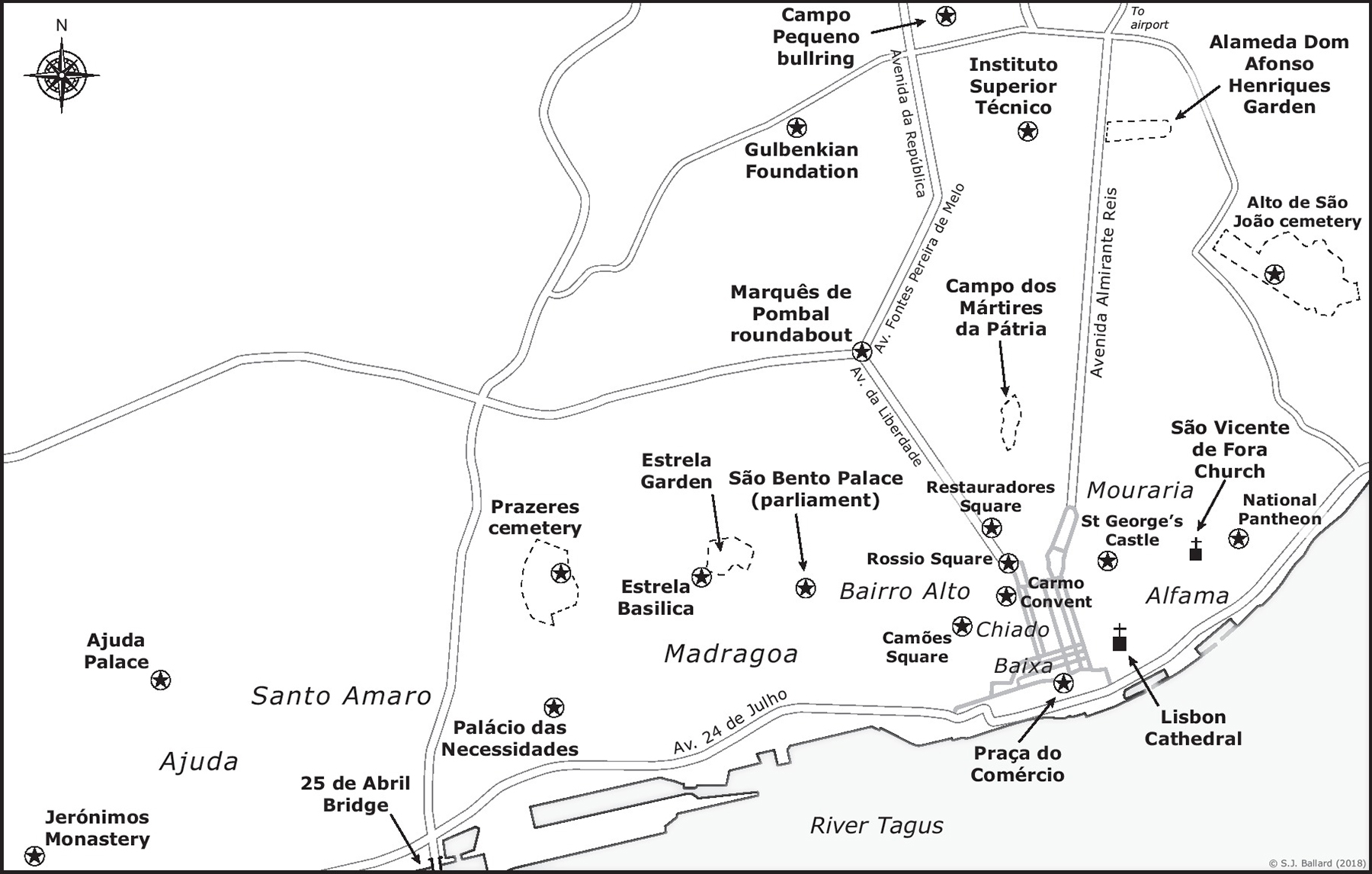

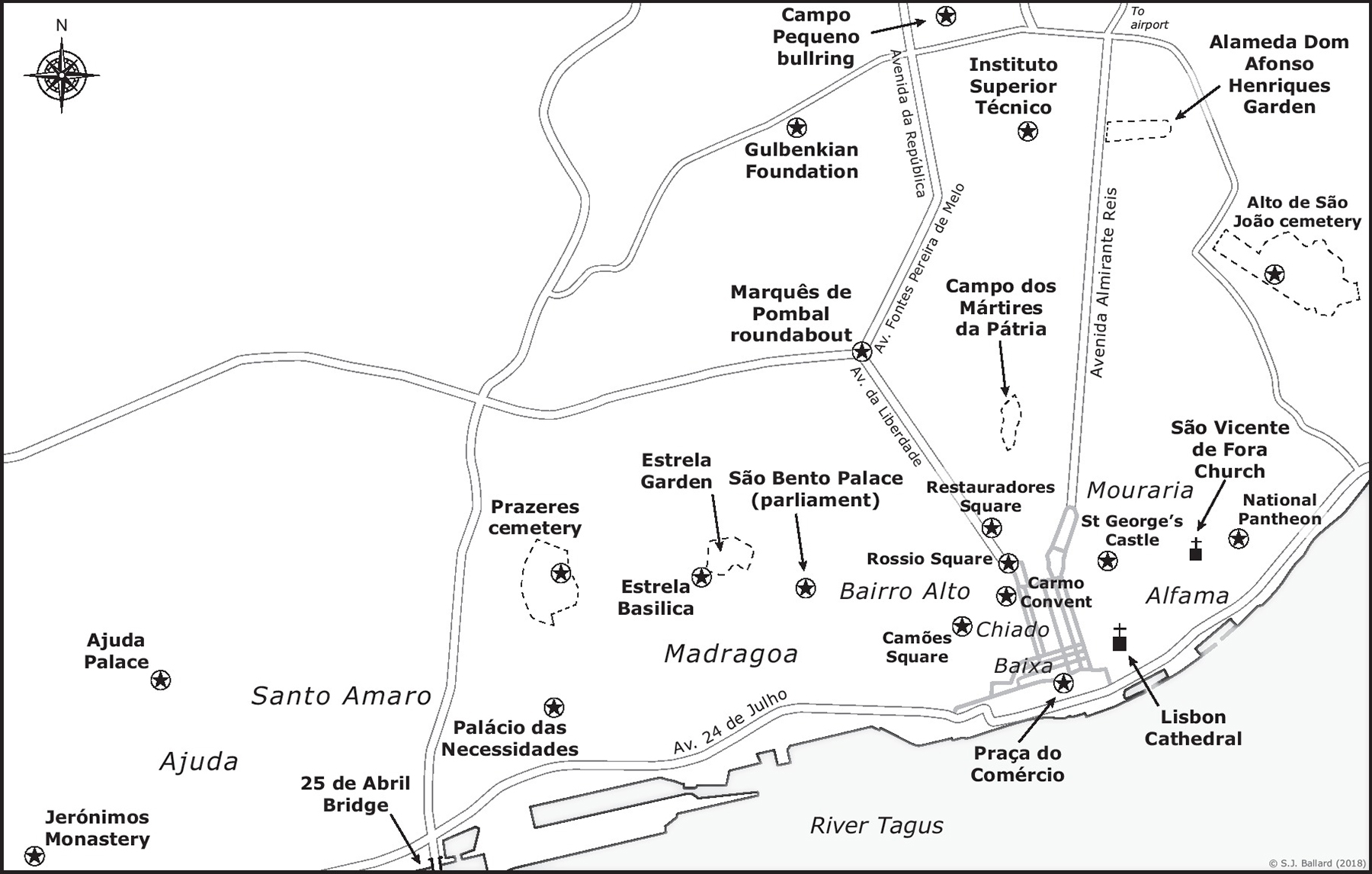

Map of Lisbon

Jan Taccoen was captivated. The Flemish nobleman had stopped over in Lisbon in 1514 on his voyage to Jerusalem, and in his nine days in the Portuguese capital he repeatedly came across three elephants with their handlers proceeding through the city. Taccoen was astounded by the rich variety of life he witnessed on Lisbons streetsnot just people from other European countries, but also from the distant and exotic lands of Africa and the Orient. You can see many animals and strange people in Lisbon, he remarked in a letter home.

The Portuguese kings cortge at the time was a remarkable sight. It was led by a rhinoceros which was followed by five elephants rigged out in gold brocade, then an Arabian horse, a jaguar, and finally the sovereign and his court. The same year Taccoen disembarked, King Manuel I sent a white Indian elephant as a present to the pope. His flaunting of wealth and national adventure had royal precedents. Before King Manuel, Prince Henry the Navigator had sent an African lion to his representative in Galway, Ireland because [the king] knew nothing of its kind had ever been seen in those parts, according to the fifteenth-century Portuguese chronicler Gomes Eanes de Zurara.

These exotic animals were the trophies of a conquering country. In the early sixteenth century, Portugal projected its power across two oceans, to three continents. After the Portuguese spent decades exploring the West African coast, Bartolomeu Dias was the first European to round the southernmost tip of Africa, in 1488, and enter the Indian Ocean. Adam Smith, the eighteenth-century political economist, judged that milestone to be one of the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind, along with the discovery of America. Vasco da Gama followed in Dias footsteps, finding his way to India and its spices, in 1498. Two years later, Pedro lvares Cabral placed a padroa stone markerfor Portugal on the coast of what would become known as Brazil. In the East, the Portuguese pushed on to the South China Sea, where they were the first Europeans the Japanese encountered. Technical ingenuity, geopolitical guile and daring ambition drove the empire. The Portuguese were full of lan. They were conspicuous operators on the world stage and played a prominent role in bringing about the early modern period of history.

The fabulous wealth Portugal harvested during those electrifying days of empire was concentrated almost entirely in Lisbon. This seat of imperial power grew into one of the busiest ports in Europe and one of the continents biggest, wealthiest and most famous cities. Lisbon was an Aladdins Cave of exotic goods. The cargo holds of the returning ships contained slaves, gold, silk, jewels, sugar and spices. The wares attracted buyers to the Portuguese capital from across medieval Europe. Lisbon was where you could purchase, along a single street, Chinese porcelain, Indian filigree, bolts of silk and other fine cloth, incense, myrrh, precious gems and pearls, pepper, ginger, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, saffron, chillies, ivory, sandalwood, ebony, camphor, amber, Persian carpets and handsomely bound books.

Those days of splendour, however, were numbered. Dark chapters lay ahead in Lisbons history. After one catastrophic eighteenth-century event, the city was almost moved somewhere else.

Barely a month after the Portuguese capital was wrecked in 1755 by what is believed to be the strongest earthquake ever to strike modern Europe, followed by a tidal wave as high as a double-decker bus and a six-day inferno that turned sand into glass, the kings chief engineer had already sketched out a handful of suggestions for rebuilding the city. Manuel da Maia, an eminent military engineer with heavy jowls who was born in 1677 and was seventy-eight years old when the quake hit, laid out the options as he saw them in a celebrated official report, known as his Dissertao.

One of the possibilities was to abandon the ancient city and relocate Lisbon to an area 10 kilometres further west, nearer the ocean. There, foundations built into solid limestone rock had mostly spared buildings from the earthquake. For a people traumatized by one of the continents deadliest catastrophes, the proposal was reasonableas well as plausibleconsidering the scale of the destruction and necessary rebuilding.

But Maia also saw amid the devastation a chance to introduce a degree of eighteenth-century urban renewal in the tightly wound medieval city. King Jos I had previously expressed enthusiasm for such modernization. The monarch became known as the reforming king for his efforts to adapt Portugal to changing times. He and his influential secretary of state Sebastio Jos Carvalho e Melo eventually opted for Maias suggestion to keep Lisbon where it waswith a twist. They approved a rebuilding project that swept away the downtowns medieval shape and replaced the sinewy streets with an airy, gridiron pattern more typical of northern and central Europe. The two epochs contributed different weaves to the citys pattern. The organic, anarchic muddle of the medieval part and the scientific sanity, uniformity and formality of the eighteenth-century rebuild furnish one of those contrasts that keep a city interesting.

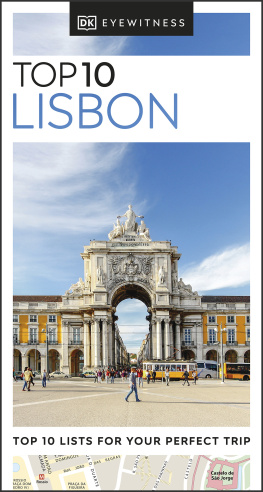

A phrase recurs in Portuguese histories of Lisbon when they describe places or buildings: Before the earthquake, this was Because in Lisbons life there will always be a Before and After that watershed event. The earthquake stripped the city of many riches it had accrued during the Age of Expansion. There are still emblematic national treasures, such as St Georges Castle and the Jernimos Monastery, though even they had to be partly rebuilt. The bottom line is that there is not such a variety of sights for visitors in Lisbon as might be encountered in cities elsewhere on the continent. Rome, it isnt.

Lisbons special appeal lies elsewhere. Its secret is in the mix. There is an afterglow of Lisbons imperial history, when the city was the nerve centre for Portugals extensive colonial possessions in Africa, South America and the Orient. That cosmopolitan legacy endows Lisbon with an intriguing, exotic flavour that is unique in Europe. Lisbon, for all its loss, still engages the imagination.