Also by Matthew Sturgis

Walter Sickert: A Life

Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography

Passionate Attitudes: The English Decadence of the 1890s

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2018, 2021 by Matthew Sturgis

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover, in a different form, in Great Britain by Apollo Books, an imprint of Head of Zeus Ltd., London, in 2018.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sturgis, Matthew, author.

Title: Oscar Wilde : a life / Matthew Sturgis.

Other titles: Oscar

Description: First American edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020054352 (print) | LCCN 2020054353 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525656364 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525656371 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Wilde, Oscar, 18541900. | Authors, Irish19th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PR5823 .S78 2021 (print) | LCC PR5823 (ebook) | DDC 828/.809 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054352

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020054353

Ebook ISBN9780525656371

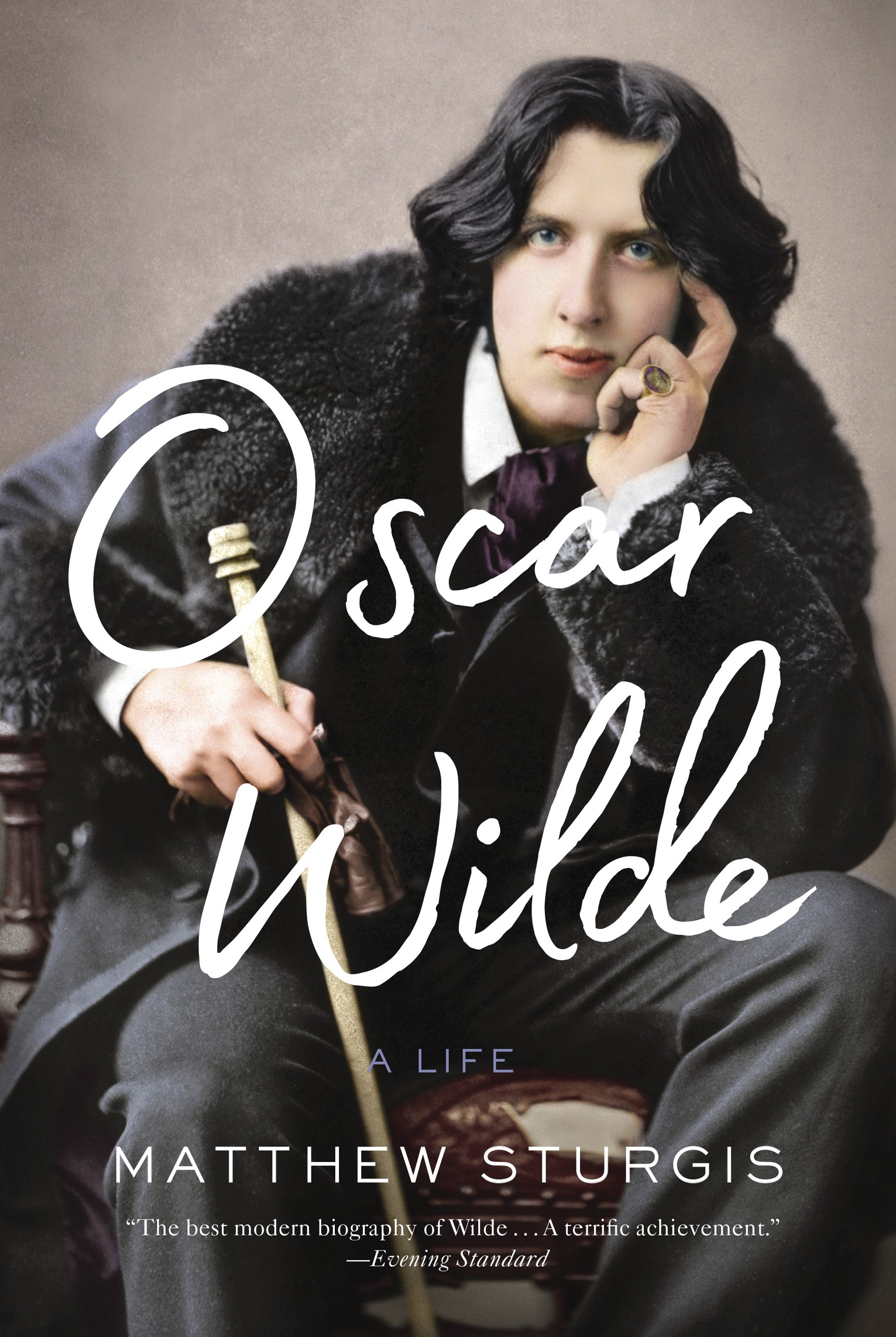

Cover photograph of Oscar Wilde, 1882, the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Colorization by Mario Unger

Cover design by Gabriele Wilson

ep_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

For Rebecca

Always

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

Oscar Wilde is part of our world. Leaving my Airbnb in New York on my way to inspect a previously overlooked Wilde letter in the library at Columbia University, I passed a chalkboard outside an Irish bar scrawled with the legend Work is the curse of the Drinking Classes. Opposite me on the uptown subway sat a girl whose mobile phone case carried the slogan To live is the rarest thing in the world. And then, to make my morning complete, walking through the university portals was a student sporting a T-shirt that declared, Genius is born, not paid. All three quotations were dulyand (as is not always the case) correctlycredited to Oscar Wilde.

Such encounters are by no means exceptional. Indeed, seeing the world through a Wildean prism, as I have done over recent years, rarely do I find a newspaper or magazine that does not contain a stray reference to Wilde or his work. And it is not simply his epigrams that have survived in the age of Twitter and shortening attention spans. His plays are still performed. His books are still read. His image is widely reproduced and instantly recognized. He regularly appears as a character on both stage and screen. He has even been turned into a detective by Gyles Brandreth.

The position he holds is an extraordinary one; it spans high and popular culture, it bridges the past and the present. Among British writers, when it comes to recognizability, he stands with Shakespeare and Jane Austen. In America perhaps Mark Twain shares something of this glamour. The French might look to Baudelaire and Proust. Wilde, however, seems likely to outstrip them all. His prominence increases with each year. His defiant individualism, his refusal to accept the limiting constraints of society, his sexual heresies, his political radicalism, his commitment to style, and his canny engagement with what is now called celebrity culture all conspire to make him ever more approachable, more exciting, and more relevant.

All this is impressive, and extraordinary, but does it mean that we need another biography of Wilde?

Soon after I began work on this book, I went to dinner at the house of some friends. My host had piled on my chair a selection of books about Wilde drawn from his own shelves. There was Hesketh Pearsons 1946 Life of Oscar Wilde, Montgomery Hydes definitive biography from 1976, and, of course, the book that supplanted it: Richard Ellmanns monumental Oscar Wilde, published in 1987.

And it was not, moreover, as if my hosts collection was anything like complete. It was just a gathering from the shelves of a general reader. There were dozens of other books that might have been added to the already tottering pilelesser biographical accounts, the memoirs of contemporaries, literary studies. Surely the story had been told (and retold), the details fixed (and refixed). The tale had become familiar.

But appearances, as Oscar knew, can be deceptive. To anyone with a more than general interest in Wilde it had been clear for some time that there was a pressing need for a new and full biography. The reasons for this are threefold. In the thirty years since Ellmanns book appeared, much new material has come to light, much interesting research has been carried out, and the deficiencies in Ellmanns biography have become ever more apparent.

As to the new material, there have been some amazing discoveries. The full transcript of the libel trial that Wilde launched against the Marquess of Queensberry was unearthed; so too were the detailed witness statements of many of those involved in the case. At the Free Library of Philadelphia, Mark Samuels Lasner and Margaret Stetz discovered (hiding in plain sight) one of Wildes early notebooks, his annotated typescript of Salom, and a long letter concerning his Ballad of Reading Gaol. Numerous other previously unknown letters were gathered up in the magnificent and much expanded new edition of Wildes letters produced by Rupert Hart-Davis and Wildes grandson Merlin Holland in 2000.

Scholarship, too, has been busy. Oxford University Press has started to produce The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde in its scholarly Oxford English Texts series; there are nine volumes so far, including two tomes of Wildes journalism, all with critical introductions and exhaustive notes. There have been many excellent specialist studiesarticles, pamphlets, books, and websiteson specific aspects of Wildes life: his work practices, his medical history, his sex life, his family background, his Irishness, his school days, his classical education, his reading, his American tour, his Liberal politics, his British lectures, his role as an editor, his fairy tales, his women friends, his love of Paris, his seaside holiday at Worthing in 1894, his Neapolitan sojourn, his final days. There have been dedicated biographies of important figures in Wildes life: his mother; his wife; the Marquess of Queensberry; Lord Alfred Douglas; such collaborators as Charles Ricketts, Pierre Lous, and Aubrey Beardsley; such friends as Carlos Blacker, More Adey, Frank Miles, and Lillie Langtry. The Oscar Wilde Society has grown and thrived over the last twenty-five years, producing an impressive and regular stream of publications. The Oscholars website has provided another useful forum for research. The need to bring together all this scattered and disparate new informationto assess it and integrate it into the record of Wildes lifehas grown more pressing with each year.

And, of course, knowledge prompts knowledge. The many additions to the record of Wildes life provided by such scholarship have encouraged new avenues of research. Certainly they have encouraged me to reinvestigate the great Wildean archives, to search out new material, to track down forgotten references, and to avail myself of the possibilities allowed by the groundbreaking digitalization of historical newspaper archives. (To anyone who can recall the long journey out to the British Library Newspaper Archive at Colindale and the eye-wearying trawl through flickering reels of microfilm in search of an elusive review or paragraph, the ease and efficiency of the new process seem quite miraculousif not almost indecent.)

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)