OSCAR

Matthew Sturgis

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

Oscar Wildes life like his wit was alive with paradox. He was both an early exponent and a victim of celebrity culture: famous for being famous, he was lauded and ridiculed in equal measure. His achievements were frequently downplayed, his successes resented. He had a genius for comedy but strove to write tragedies. He was an unabashed snob who nevertheless delighted in exposing the faults of society. He affected a dandified disdain but was given to great acts of kindness. Although happily married, he became a passionate lover of men and at the very peak of his success brought disaster upon himself. He disparaged authority, yet went to the law to defend his love for Lord Alfred Douglas. Having delighted in fashionable throngs, Wilde died almost alone: barely a dozen people were at his graveside.

Yet despite this ruinous end, Wildes star continues to shine brightly. His was a life of quite extraordinary drama. Above all, his flamboyant refusal to conform to the social and sexual orthodoxies of his day make him a hero and an inspiration to all who seek to challenge convention.

In the first major biography of Oscar Wilde in thirty years, Matthew Sturgis draws on a wealth of new material and fresh research to place the man firmly in the context of his times. He brings alive the distinctive mood and characters of the fin de sicle in the richest and most compelling portrait of Wilde to date.

For Tim and Jean

Oscar Wilde is part of our world. Leaving my Airbnb in New York on my way to inspect a previously overlooked Wilde letter in the library at Columbia, I passed a chalkboard outside an Irish bar scrawled with the legend, Work is the curse of the Drinking Classes. Opposite me on the Uptown subway sat a girl whose mobile-phone case carried the slogan, To live is the rarest thing in the world. And then, to make my morning complete, walking through the university portals was a student sporting a T-shirt that declared, Genius is born, not paid. All three quotations were duly and (as is not always the case) correctly credited to Oscar Wilde.

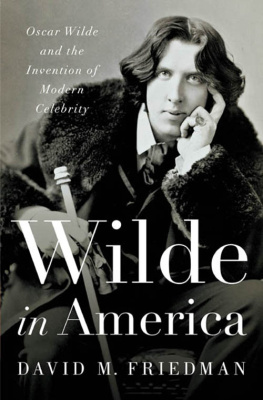

Such encounters are by no means exceptional. Indeed, seeing the world as I have done over recent years through a Wildean prism, it seems to me that rare is the newspaper or magazine that does not contain a stray reference to Wilde or his work. And it is not simply his epigrams that have survived in the age of Twitter and shortening attention spans. His plays are still performed. His books are still read. His image is widely reproduced, and instantly recognized. He regularly appears, as a character, on both stage and screen. He has even been turned into a detective by Gyles Brandreth.

The position he holds is an extraordinary one; it spans high and popular culture, it bridges the past and the present. Among British writers he stands with Shakespeare and Jane Austen. In America perhaps Mark Twain shares something of this glamour. The French might look to Baudelaire and Proust. Wilde, however, seems likely to outstrip them all. His prominence increases with each year. His defiant individualism, his refusal to accept the limiting constraints of society, his sexual heresies, his political radicalism, his commitment to style and his canny engagement with what is now called celebrity culture, all conspire to make him more approachable, more exciting and more relevant.

All this is impressive, and extraordinary, but does it mean that we need another biography of Wilde?

Soon after I began work on this book, I went to dinner at the house of some friends. My host had piled on my chair a selection of books about Wilde drawn from his own shelves. There was Hesketh Pearsons 1946 Life of Oscar Wilde , Montgomery Hydes definitive biography from 1976, and, of course, the book that supplanted it: Richard Ellmanns monumental green volume Oscar Wilde , published in 1987.

And it was not, moreover, as if my hosts collection was anything like complete. It was just a gathering from the shelves of a general reader. There were dozens of other books that might have been added to the already tottering pile lesser biographical accounts, the memoirs of contemporaries, literary studies. Surely the story had been told (and retold), the details fixed (and refixed). The tale had become familiar.

But appearances, as Oscar knew, can be deceptive. To anyone with a more than general interest in Wilde it had been clear for some time that there was a pressing need for a new and full biography. The reasons for this are threefold. In the thirty years since Ellmanns book appeared, much new material has come to light, much interesting research has been carried out, and the deficiencies in Ellmanns biography have become ever more apparent.

As to the new material: there have been some amazing discoveries. The full transcript of the libel trial that Wilde launched against the Marquess of Queensberry was unearthed; so too were the detailed witness statements of many of those involved in the case. At the Free Library of Philadelphia, Mark Samuels Lasner and Margaret Stetz discovered (hiding in plain sight) one of Wildes early notebooks, his annotated typescript of Salom and a long letter concerning his Ballad of Reading Gaol . Numerous other previously unknown letters were gathered up in the magnificent, and much expanded, new edition of Wildes letters, produced by Rupert Hart-Davis and Wildes grandson Merlin Holland in 2000.

Scholarship, too, has been busy. Oxford University Press has started to produce The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde in its scholarly Oxford English Texts series; there are seven volumes so far, including two tomes of Wildes journalism, all with critical introductions and exhaustive notes. There have been many excellent specialist studies articles, pamphlets, books and websites on specific aspects of Wildes life: his working practices, his medical history, his sex life, his family background, his Irishness, his schooldays, his classical education, his reading, his American tour, his Liberal politics, his British lectures, his role as an editor, his fairy tales, his women friends, his love of Paris, his Neapolitan sojourn; his final days. There have been dedicated biographies of important figures in Wildes life: his mother; his wife; the Marquess of Queensberry; Lord Alfred Douglas; such collaborators as Charles Ricketts, Pierre Lous and Aubrey Beardsley; such friends as Carlos Blacker, More Adey, Frank Miles and Lillie Langtry. The Oscar Wilde Society has grown and thrived over the last twenty-five years, producing an impressive and regular stream of publications. The Oscholars website has provided another useful forum for research. The need to bring together all this scattered and disparate new information to assess it and integrate it into the record of Wildes life has grown more pressing with each year.

And, of course, knowledge prompts knowledge. The many additions to the record of Wildes life provided by such scholarship have encouraged new avenues of research. Certainly they have encouraged me to re-investigate the great Wildean archives, to search out new material, to track down forgotten references and to avail myself of the possibilities allowed by the groundbreaking digitalization of historical newspaper archives. (To anyone who can recall the long journey out to the British Library Newspaper Archive at Colindale, and the eye-wearying trawl through flickering reels of microfilm in search of an elusive review, or paragraph, the ease and efficiency of the new process seems quite miraculous if not almost indecent.)

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)