Contents

Guide

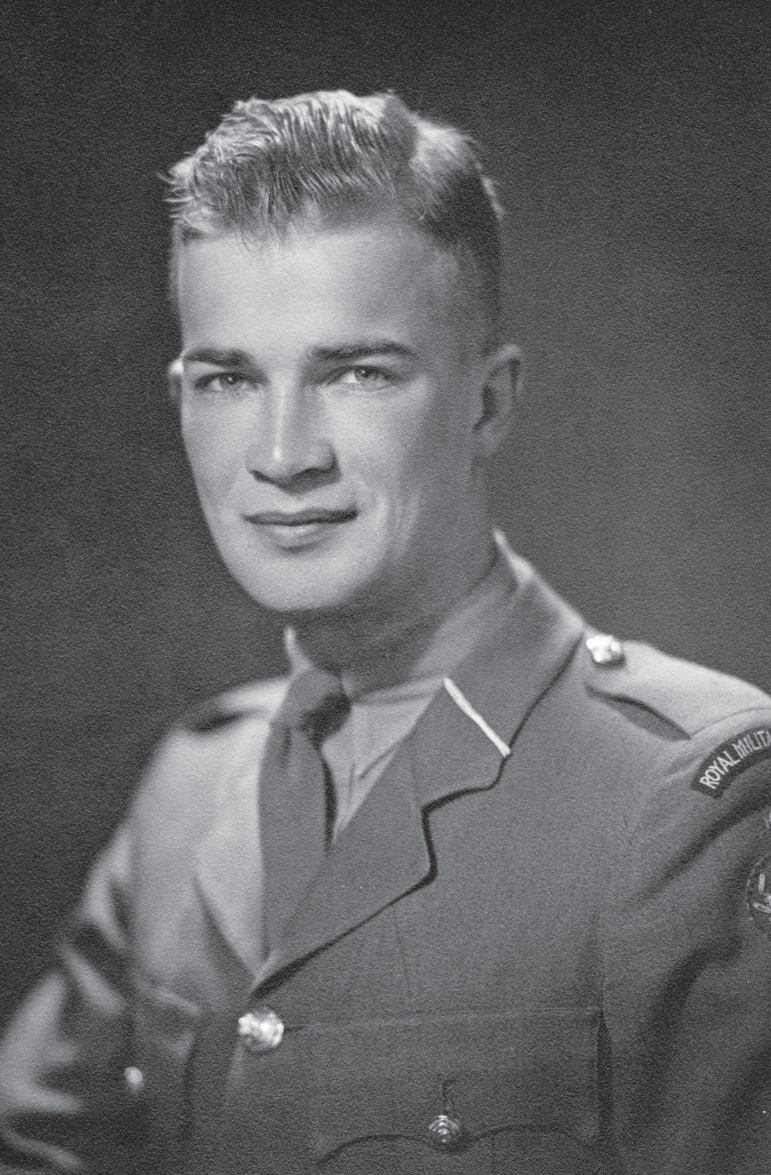

For my parents, Elizabeth and Ronald

Contents

A knife, a diary, a recipe book, a string instrument, and a cotton pouch. Each belonged to an individual in their twenties during the Second World War: a fresh-faced prairie boy, a melancholic youth, a capable cook, a musician wounded at the front, and a survivor.

Try asking your friends, over a cup of tea, what object theyd choose to represent their lives. The enthusiasm of their responses will give you an indication of how well objects anchor sprawling personal histories. I talked to elderly family members, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances people drawn from everyday life asking them the same question: is there a belonging that tells your wartime story? In most cases, I asked the question in reverse. Can I discover the Second World War story of a deceased person through an object they owned?

I had to make difficult choices to pare the book down to five objects. I found that even the most ordinary of them could tell a spectacular story; they are no less extraordinary or meaningful than famous examples.

Historians of material history those who occupy themselves with what objects can tell us about the past often divide their work into object-centred histories and object-driven histories. In the former, the objects are the focus of their owners stories. In the latter, the objects might stand slightly left-of-centre but they nonetheless help us reveal something that would otherwise be hidden. In this book, I do a little of both; there are variations on a theme. Ultimately, in both cases, the belongings remain tools even strategies to draw out a witnesss narrative. I think of them like attractors, dipped into the solution of history that then form crystals of memory.

Now, your neighbours may be more or less interesting than mine. I would never claim that my next-door objects are an uncomplicated sample from the pond of history. Im a Canadian who moved to Berlin more than a decade ago an outsider who teaches this material at a university in the German capital. But I am certain that almost any reader of this book provided they have neighbours and family who remember the war will make remarkable discoveries about the past if they start asking around. And I am also convinced that my everyday discoveries will resonate with people who never met my neighbours.

The most exciting aspect of writing this book has been the detective work. Unpacking these next-door histories is at times inspiring, at others disheartening (and its about the heart when you begin to know each individual intimately). But the step-by-step thrill of discovery was something I wanted to share.

As an unlikely mix of historian-meets-literary writer, Ive often scratched my head at why history doesnt more often employ tools of creative writing to tell engaging but true stories ones that capture the texture of the past. My response was to write the chapters as documentary short stories of stumbling across Second World War witnesses, learning about their belongings and everyday histories, uncovering their secrets. The resulting book intentionally does not read like traditional history.

To reassure the general reader and the specialist: there is something here for you both. The former might spend more time with the stories, the latter with the concluding chapter of analysis and endnotes. To enjoy me at my most pedantic, you may read from the back, where I tie the theoretical problems to a dozen further objects to give context in the field of material history. Throughout, I argue how Nazi-era objects are especially vulnerable to opportunistic narratives as screens for our fantasies, our projections in the absence of their owners and careful detective work.

This object history of memory is being written at an urgent turning point, one of generational change. The public health emergency of Covid-19 has disproportionately affected the war generation. Consider the following: a 22-year-old in the last year of the Second World War is 99 years old in 2022. Most of the witnesses for this book were about this age when interviewed. They are the last witnesses. I am worried what happens to their belongings when they are gone because, on their own, these things dont speak. Line them up on a table, try talking to them one by one, and I bet you wont get a word out of them. Its as if they were charmed, and their stories only summoned by those people who had direct experience of this most violent moment in world history. This momentary spell gives the objects value.

The line between the junkyard and the museum is a good story. Since knowing their stories as you will its become difficult for me to see the objects as just flotsam. It pains me to imagine them collecting dust on the shelf of a second-hand shop or in a storage locker. But a generation that has not experienced war, whose members are unable to interpret the jetsam of the past, will more easily discard or misinterpret these things. Think of a belonging of sentimental value you own an engagement ring, an admission ticket, a stone from a beach which will become meaningless the moment you are no longer there to tell its story.

It is no coincidence that resurgent nationalism and xenophobia gain ground and not just in Germany as we lose those who saw their extreme consequences. Because many stories can be spun from these objects, but not all of them are true.

Berlin, December 2021

The Knife

My grandfather kept a knife with a swastika on the wall in his basement. When I was small, he took me down to see it, and it frightened me. It hung cold from its hook, surrounded by other weapons the veteran had collected or inherited. There was the riding crop and sword of my great-great-grandfather, a colonel from the Boer War. The colonels sword was imbued with positive feelings: the material was bright and shiny and silver, and I had read enough fairy tales to want a sword.

But, even at the age of 6 or 7, I knew to distrust the knife in its scabbard. I did not have the words then nor really now to describe its negativity. Was it the silver eagles head, decorated with carved feathers? That it was bolted with a layer of bone human? below the elaborately carved hilt of laurels? Was it the scabbard, of worn leather, for the ferocious blade that had brushed against some trouser leg?

When my grandfather took it down from the wall and unsheathed it, the knife made an efficient sound a slide and a click. This was so unlike the elegantly resounding ring of the colonels sword. And when he lowered it into my hands, I looked into the blank eye of the eagle. I examined all the Xs carved into the silver of its hilt. I turned it over, fascinated with the insignia of the eagle, wings spread, also wreathed with laurel leaves, all surmounting the swastika.

My grandfather told me that he had liberated the knife as a captain in the Canadian forces in 1944 or 1945 in the Netherlands. My father told me a different story perhaps to protect me which was that he found it in the mud somewhere. At that age, the word liberate was a positive one. I did not for a moment think that it could be a euphemism for capturing or killing the enemy.

Many years later after my studies and time spent living in many places, with possessions scattered between college storage, my parents house, and lockers in Cambridge, New York, Nottingham, Vancouver, and Edmonton I settled down and ended up living in the capital of my grandfathers enemy. I have been living among the defeated in Berlin for more than a decade now.

My grandfather died in 2005, and I never paid much attention to his will, except for a couple of details: he left me both my great-great-grandfathers sword and his Nazi knife. The sword was outside normal baggage restrictions (its still in my parents basement and I wonder if I should transport it with golf clubs one day). But the Nazi knife had vanished; no one knew what had happened to it. Thank goodness, my aunt told me. It was so horrific. Stuff like that should just disappear.