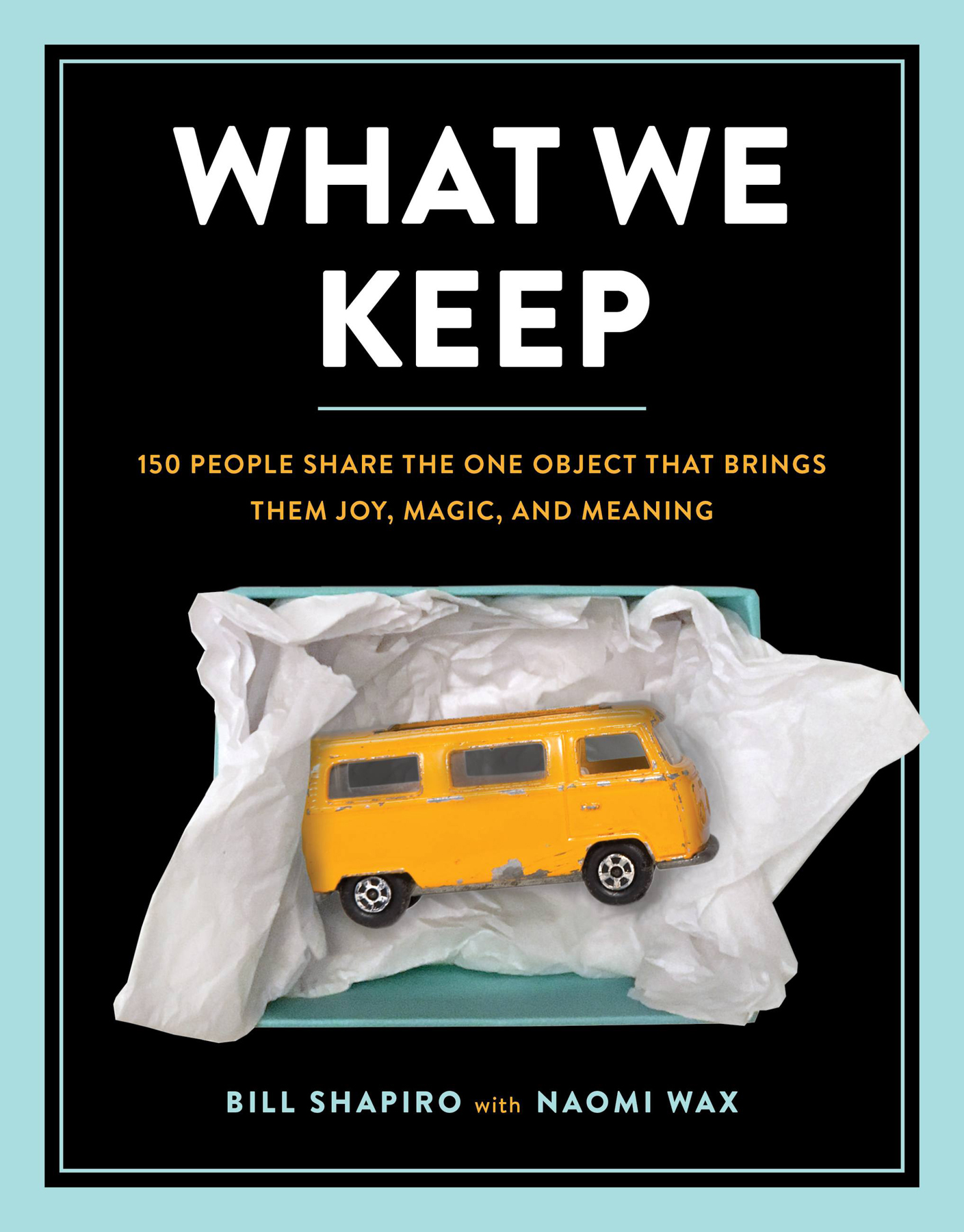

Copyright 2018 by Bill Shapiro

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Running Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com

@Running_Press

First Edition: September 2018

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Photography credits appear

Portion of cover photo Getty Images

illustration: 2018 MARVEL

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933852

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6254-4 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-6255-1 (ebook)

E3-20180811-JV-PC

for

SASHA, SOREN & JONAH

With love, more love, and three slices of cherry pie.

LETS START HERE

IN THIS BOOK, you will find the story of a bottle opener that a drug-dealing grandmother gave to her grandson. The strange pincushion that foreshadowed a future writers wanderings. The bullet a soldier would have used to kill himself had his mission gone south. The notebook sketch that sparked a hit movie.

What you wont find is the story of the locket that, in small and subtle ways, led to the idea for the book itself.

Naomi and I were poking around a yard sale in rural New York when, next to a Vietnam-era Zippo, she spotted a locket. Inside, the inscription read, My Love Forever in letters now faded by time. There was a date, too: 1911. The locket was so delicate, so beautiful, so personal that it was hard to fathom how it had ended up here, at the end of some driveway, for sale to strangers. Maybe it had belonged to the homeowners wife whod run away with her lover! Maybe it had turned up under a loose floorboard, like in a scene from a cheesy movie. More likely, the locket had simply been passed down so many times that the connection to its original owner had been lost.

I spoke with the young woman running the sale; she didnt have a clue about the lockets history. (The home belonged to her aging uncle, whod relocated to Texas.) We left the locket for someone else, but walked away kind of fixated on how once an object is separated from its story, its importance begins to fade. We thought about the objects that take on meaning in peoples lives, those treasures, trophies, and keepsakes we display on our shelves, stash in our drawers, tuck into our pockets, that move with us from home to home, that provide us with comfort simply because we know theyre there. And we became intrigued by the stories that get wrapped tightly, if temporarily, around them.

EXPLORING OUR ATTACHMENTS to objects isnt exactly a new line of inquiry. Neanderthals, no doubt, sat around this mind-blowing thing called fire and asked each other what theyd drag away should the cave alight. And yet, today, as every turn of season seems to bring biblically destructive hurricanes, floods, and, yes, fires, more and more of us find ourselves facing the no-longer-theoretical questionwhat would I take?in real time and with real consequences. Those of us spared from each new disaster quietly give thanks, but do so with a growing sense that as our climate changes, we, too, may have to choose, grab, and go.

Of course its not just our climate thats changing. The drive to have less stuff is clearly in the Zeitgeist: Our books, music, and photographs have moved from our shelves to the cloud, and the sharing economy encourages us to borrow rather than own; at the same time, were seeing a cultural shift toward valuing experiences over things. And with the Tiny House movement nudging Americans to trade in that McMansion for 400 clutter-free square feet, its not surprising that Marie Kondo has sold more than five million books urging us to rid ourselves of those possessions that fail to spark joy.

AGAINST THIS BACKDROP, Naomi and I began looking more closely at the objects in our own lives. Why had she held on to a pair of shredded blue jeans that she first wore in high school? Why did I still have a hand-scrawled hitchhiking sign from a trip through Germany 30 years ago? As we shared the stories behind these objects and the meaning they held for us, aspects of our lives emerged that wed never talked about with each otheror even really articulated to ourselves. That seemed interesting.

And so we began asking our friends about the objects theyve kept, then friends of friendsand then we cast a wider net. Our research took us on a poky, 1,600-mile road trip through the Great Plains states where we lingered in one-stoplight towns with names like Elk Horn, Dell Rapids, and Ida Grove. We talked with folks in the coffee shops, meat lockers, and mayors offices where they worked, and heard stories about objects carried across the Rockies in a covered wagon; brought back from Novosibirsk, Siberia; pawned and later repurchased.

In the end, we interviewed people from all over the country, in red states and blue, some well-known and some who wished to remain anonymous, one percenters and those with (almost) nothing. This book is a compendium of their treasured possessions and the often untold histories behind them.

One thing in particular that struck us: Of the more than 300 people we spoke with, not one chose an object because of its dollar value. Our hearts are not accountants; we cling to the meaningful, not the monetary. What makes these objects so evocative for us is that they hold the memories of people, of relationships, of places and moments and milestones that speak to our own identity. Sometimes they connect us to a time in our life when we realized all that we were capable of. Sometimes they connect us to the best weve seen in others and to what we aspire to beand beyond that, as the Grateful Deads longtime publicist put it in my conversation with him, to our place in the ongoing pageant of human drama. What Naomi and I came to see is that these bottle openers and bullets, these playing cards, letters, and lockets not only crystallize core truths about each of us but also help us tell the stories of our life, even explain our life to ourselves. And for that reason, theyre priceless.