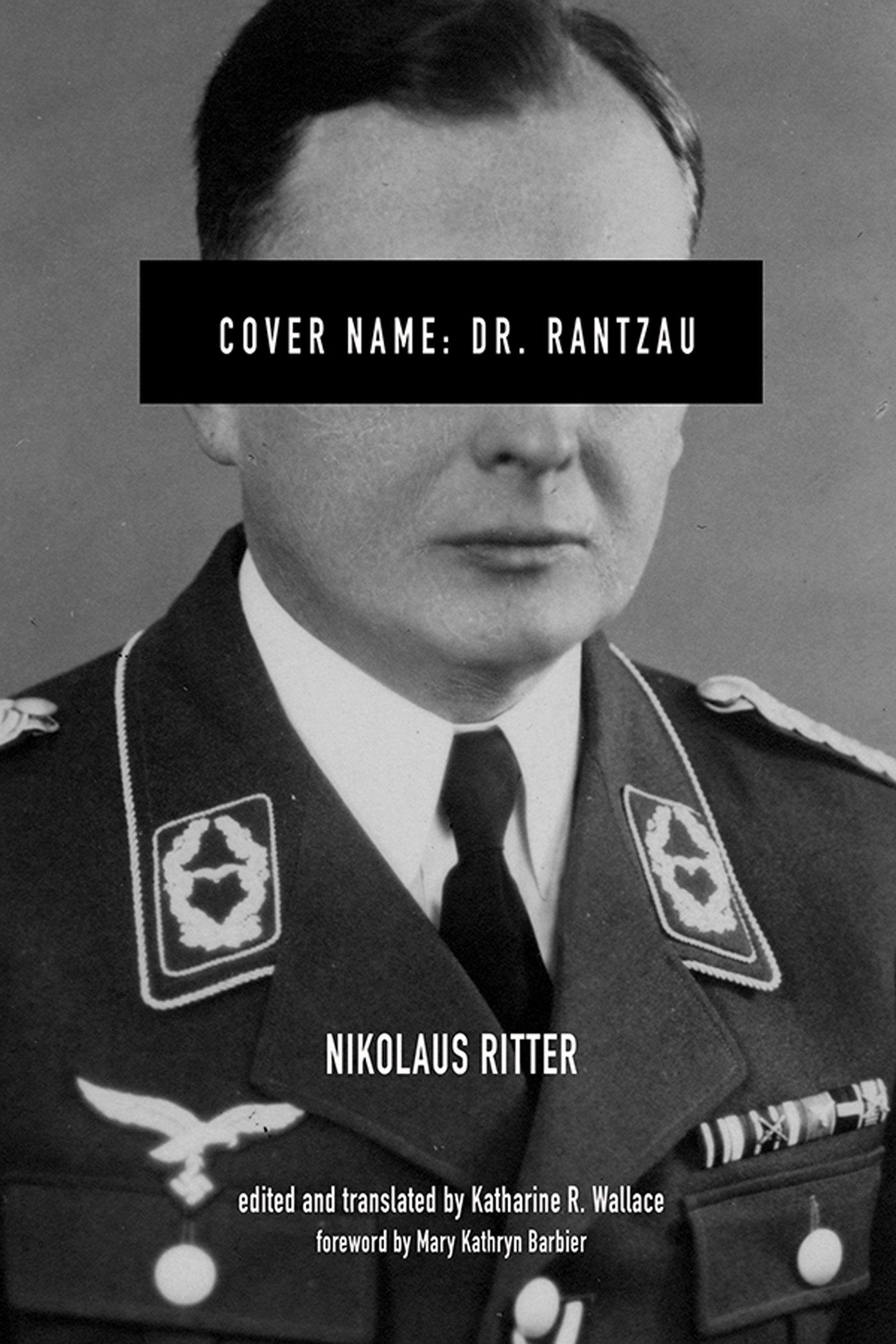

Cover Name: Dr. Rantzau

FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES

History is replete with examples of notable military campaigns and exceptional military leaders and theorists. Military professionals and students of the art and science of war cannot afford to ignore these sources of knowledge or limit their studies to the history of the US armed forces. This series features original works, translations, and reprints of classics outside the American canon that promote a deeper understanding of international military theory and practice.

SERIES EDITOR: Joseph Craig

An AUSA Book

Cover Name: Dr. Rantzau

Nikolaus Ritter

Edited and translated by Katharine R. Wallace

Foreword by Mary Kathryn Barbier

Copyright 2019 by Katharine R. Wallace

The original German edition of this book was published as Deckname Dr. Rantzau: The Records of Nikolaus Ritter, Officer under Canaris in the Secret Intelligence Service (Hamburg: Hoffman und Campe, 1972). First English language edition published by the University Press of Kentucky.

The University Press of Kentucky,

scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-7734-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7735-9 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-7736-6 (epub)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association

of University Presses |

For Ian, Thomas, and Kate

A glimpse of your history

Spying as such is not a crime; it is not even immoral, provided it is not pursued out of greed, but rather for the sake of patriotism.

Friedrich von Martens, Das Internationale Recht der zivilisierten Nationen [International Law of Civilized Nations]

Contents

Mary Kathryn Barbier

Katharine R. Wallace

Foreword

During World War II, as has been the case in most conflicts, particularly modern ones, the major nations involved engaged in the intelligence-gathering game by employing spies and double agents. It was imperative to learn the enemys plans and to counter them. Understanding the extent of the enemys military might was crucial to defeating them. Neutral countries like Switzerland and Portugal became playgrounds for spies and their contacts as they engaged in their craft; however, intelligence-gathering operations occurred in other locations. For example, in 1943 the British ambassador based in Ankara, Turkey, was compromised when Elyesa Bazna (aka Cicero), his Albanian-born valet, systematically photographed highly classified documents, which he then sold to the Germans.1 Richard Sorge, an undercover German journalist, set up abriefly lucrativespy ring in Japan, where he gathered information for his real bosses, the Soviets.

Some spies, known as double agents, worked for both sides. Some of these double agents volunteered for their new roles. Others chose the lesser of two evils. Working for the enemy beat the alternativedeath. While some double agents provided information about damage caused by bombs, the location of airfields, the training and movement of troops, and factory output, others served a more targeted purpose. They participated in deception operations designed to mislead their original employers or to increase the possibility of their new bosses success in battle. For instance, scholars have shed light on Operation Fortitudethe Allied cover plan for the Normandy invasionthat has revealed the use of double agents in what was initially a secret, undercover operation. In the aftermath of the Second World War, spies, double agents, and handlers remained, for the most part, reticent to speak or write about their wartime activities.

With the advent of the Cold War and the ratcheting up of the espionage and counterespionage game, the climate wasnt right for transparency. In the last few decades, however, shifting winds have cleared the way for firsthand accounts, historical narratives, and movies about the espionage game. The spy novels written by John le Carr and Ian Fleming, among others, helped pave the way. Along with the James Bond movies, they romanticized and glorified the work of spies. Secret agents with access to incredible gadgets represented good and successfully defeated evil time and again. While James Bond, George Smiley, and others like them operated during the Cold War, the roots of these fictional characters can be found in the real-life Second World War spies, double agents, and spymasters, like Nikolaus Ritter, some of whom experienced lives fraught with excitement, intrigue, and danger.

Numerous men and women did their part for the war effort by working for the intelligence services. Not all of them gained notoriety after the war, but as time has passed, more and more of them have had their stories told. British agent William Stephenson established a spy network that successfully operated against the Germans throughout the war. Virginia Hall, or the Limping Lady, first a member of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and then of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), worked with the French Resistance during the war. Her work was so damaging that the Gestapo put a price on her head.

Several spies worked both sides, and their stories have added a new layer to an understanding of the espionage game. Eddie Chapman, aka Zigzag, a longtime criminal, chose to circumvent the pitfalls of living under occupation by becoming a spy for the Germans and then selling them out to the British. Seeming to flit back and forth between the two intelligence services, Chapmans loyalties were hard to determine. Three who willingly became German spies and acted as double agents to help bring down Germany were Dusko Popov (Tricycle), Juan Pujol Garcia (Garbo), and Lily Sergueiew (Treasure). Each in his or her own way contributed to Operation Fortitude. Each had a personal agenda in agreeing to spy for Germany, and each understood the dangers of their chosen path.2

What has become increasingly apparent, as more firsthand accounts and other narratives about these spies and double agents are published, is that the story is generally not told from the perspective of the handlerthe spymaster. In addition, the majority of the recent English-language publications provide the inside story of American, British, or French, but not German, spies and double agents.

Next page