Human nature does not change much over time, but politics and technology do. Books dealing with specific periods in the past often crash for the general reader if the context in which events took place is unfamiliar, or if the terminology is outdated and strange. Before beginning, the reader might like to glance through Appendix: The Historical Context.

Introduction

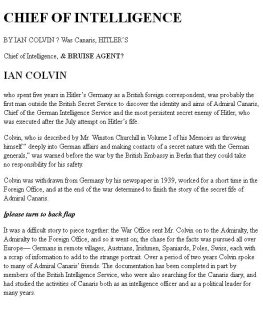

In his book Chief of Intelligence (1951), British journalist Ian Colvin wrote that he was having lunch with a senior official in one of the ministries a few years after the Second World War and in conversation asked him how he thought British intelligence had done. The man replied with some emphasis: Well, our intelligence was not badly equipped. As you know, we had Admiral Canaris, and that was a considerable thing.

Colvin did not know. The civil servant had made the mistake of assuming that because Colvin had been in Berlin before the war, and had sent back valuable information on the activities of those opposed to Hitler, he had been an agent of British intelligence himself. He had not been.

The official left it at that, but the incident set Colvin on a quest. He knew from his own experiences that Admiral Canaris, the wartime head of the Abwehr, the German intelligence service, had worked against Hitler. But a British agent?

As I walked away from lunch that day it seemed that this must be the best-kept secret of the war. From then on, however, it was a brick wall with the exception of one veteran of the War Office who said: Ah, yes, he helped us all he could. He said no more.

Colvin had no access to secret documents, especially those of the Foreign Office and War Office, much less those of MI5 and MI6 Britains Security Service and Secret Intelligence Service respectively but some of the officers close to Canaris had survived the war and he went to Germany and talked with them. Each had his own fragment of the Canaris story, and Colvin pieced together their memories. Apparently, Canaris did tip the British off to Hitlers moves against Czechoslovakia in 1938, and did foil his attempt to bring Spain into the war in 1940. He also forewarned the British of Operation Barbarossa, the 1941 invasion of Russia, and had been party to two attempts to kill Hitler.

It may have been a little too much to describe Canaris as a British agent, Colvin concluded, but from what he was told, his omissions in the intelligence field helped the Allies to achieve surprise and brought their certain victory mercifully closer. He also found that Canaris was a passive player in the conspiracies against Hitler, rather than a principal actor.

Colvin had to rely on hearsay. Thus, the debate has gone back and forth over the ensuing decades, between those writers who portrayed Canaris as an unsung hero of the German opposition against the Nazis and those mainly British who have presented him as the ineffectual chief of a corrupt and inefficient secret service. By the end of the 1970s, the latter view had won out.

Documents released in Britain and the United States since the 1990s, however, combined with captured German records that have been available all along, show Canaris to have been a central figure in the German army conspiracies against Hitler and, even more remarkable, that the Abwehr under his direction had decisively intervened on the side of Germanys enemies in some of the major events of the war, most notably the 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the 1944 Battle of Normandy.

This is much more than Colvin, or most of the contemporaries of Canaris, could ever have dreamed of.

The newly opened MI5 files are very incomplete. They have been extensively censored and weeded, both officially and apparently surreptitiously the damage being so enormous that the British security and intelligence services themselves may have lost sight of much of their wartime past. It can be recovered at least partially, however, by matching the newly released material to corresponding intelligence documents held abroad, and the surviving records of the Abwehr.

The situation is better in the United States, the relevant archives being those of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Office for Strategic Services (OSS) the wartime forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The number of available files is enormous, for the Americans spared no expense in trying to determine how the German secret services, both army and Nazi, conducted operations. Many of the FBI/OSS files complement those of the British, and what is apparently missing on one side of the Atlantic can sometimes be found on the other.