This edition is published by BORODINO BOOKS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books borodinobooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2003 under the same title.

Borodino Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

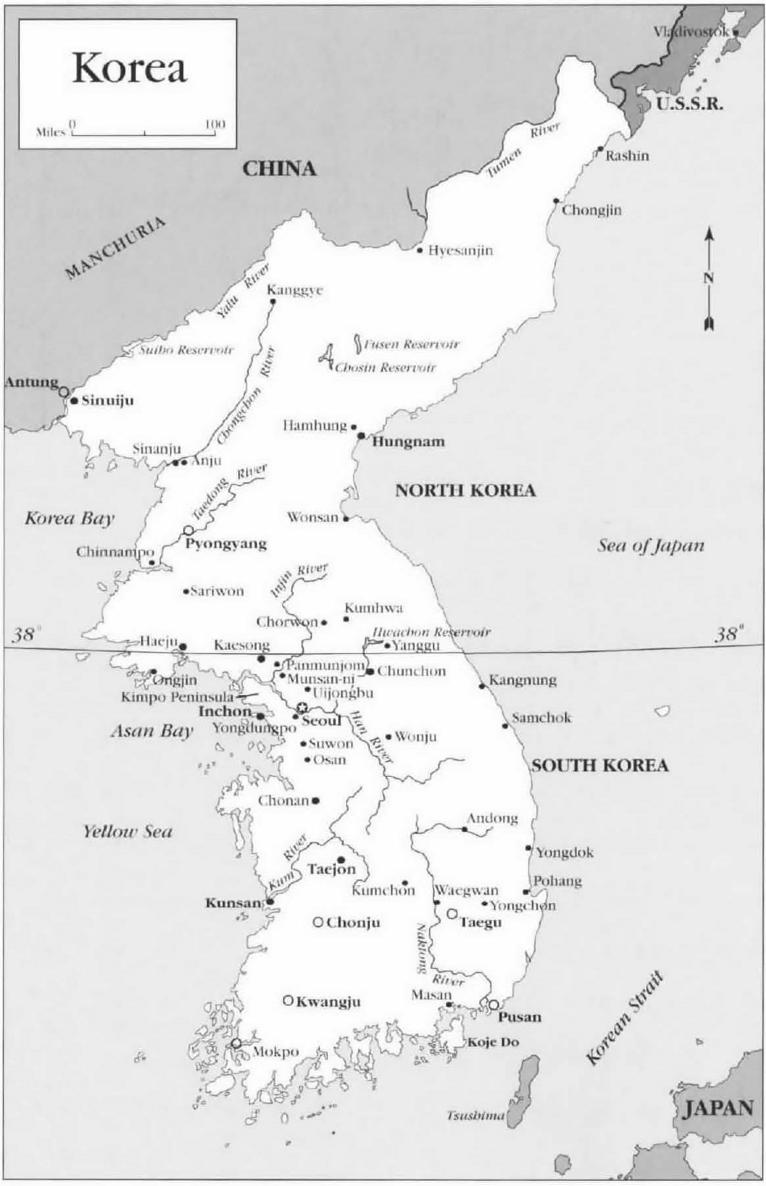

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

WHIRLYBIRDS

U.S. Marine Helicopters in Korea

By

Lieutenant-Colonel Ronald J. Brown, USMCR (Ret)

INTRODUCTION

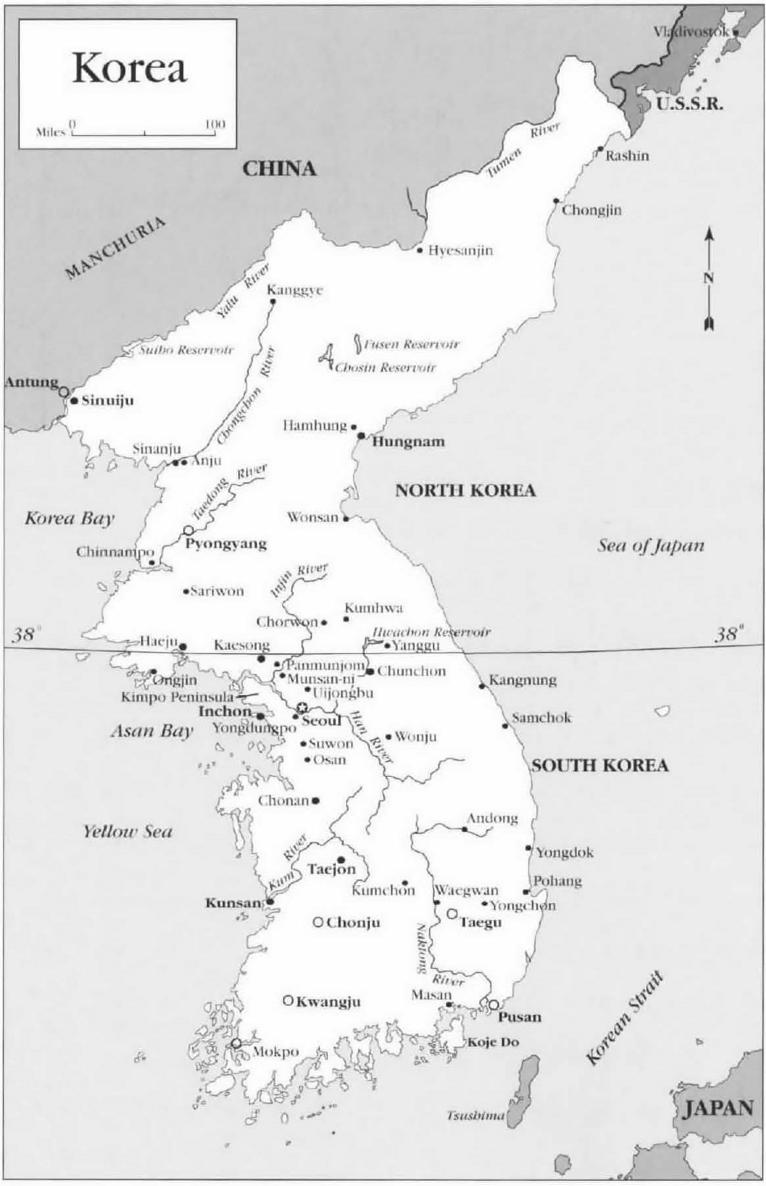

On Sunday, 25 June 1950, Communist North Korea unexpectedly invaded its southern neighbor, the American-backed Republic of Korea (ROK). The poorly equipped ROK Army was no match for the well prepared North Korean Peoples Army (NKPA) whose armored spearheads quickly thrust across the 38 th Parallel. The stunned world helplessly looked on as the outnumbered and outgunned South Koreans were quickly routed. With the fall of the capital city of Seoul imminent, President Harry S. Truman ordered General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief, Far East, in Tokyo, to immediately pull all American nationals in South Korea out of harms way. During the course of the resultant non-combatant evacuation operations an unmanned American transport plane was destroyed on the ground and a flight of U.S. Air Force aircraft were buzzed by a North Korean Air Force plane over the Yellow Sea without any shots being fired. On 27 July, an American combat air patrol protecting Kimpo Airfield near the South Korean capital actively engaged menacing North Korean planes and promptly downed three of the five Soviet-built Yak fighters. Soon thereafter American military forces operating under the auspices of the United Nations Command (UNC) were committed to thwart a Communist takeover of South Korea. Thus, only four years and nine months after V-J Day marked the end of World War II, the United States was once again involved in a shooting war in Asia.

The United Nations issued a worldwide call to arms to halt Communist aggression in Korea, and Americas armed forces began to mobilize. Marines were quick to respond. Within three weeks a hastily formed provisional Marine brigade departed California and headed for the embattled Far East. Among the aviation units on board the U.S. Navy task force steaming west was a helicopter detachment, the first rotary-wing aviation unit specifically formed for combat operations in the history of the Marine Corps. Although few realized it at the time, this small band of dedicated men and their primitive flying machines were about to radically change the face of military aviation. Arguably, the actions of these helicopter pilots in Korea made U.S. Marines the progenitors of vertical envelopment operations, as we know them today.

HELICOPTERS IN THE MARINE CORPS

There is great irony in the fact that the Marine Corps was the last American military Service to receive helicopters, but was the first to formulate, test, and implement a doctrine for the use of rotary-wing aircraft as an integral element in air-ground combat operations. The concept of manned rotary-wing flight can be traced back to Leonardo da Vincis Renaissance-era sketches, but more than four centuries passed before vertical take-offs and landings by heavier-than-air craft became a reality. The Marines tested a rotary-wing aircraft in Nicaragua during the Banana Wars, but that experiment revealed the Pitcarin OP-1 autogiro was not ready for military use. Autogiros used rotary wings to remain aloft, but they did not use spinning blades to get airborne or to power the aircraft so autogiros were airplanes not helicopters. Some aviation enthusiasts, however, assert that the flight data accumulated and rotor technology developed for autogiros marked the beginning Marine Corps helicopter development. It was not until 1939 that the first practical American helicopter, aircraft designer Igor I. Sikorskys VS-300, finally moved off the drawing board and into the air. The U.S. Army, Navy, and Coast Guard each acquired helicopters during World War II. The bulk of them were used for pilot training, but a few American-built helicopters participated in special combat operations in Burma and the Pacific. These early machines conducted non-combatant air-sea rescue, medical evacuation, and humanitarian missions during the war as well.

In 1946, the Marine Corps formed a special board headed by Major-General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., to study the impact of nuclear weapons on amphibious operations. In accordance with the recommendations made by the Shepherd Board in early 1947, Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia, began to formulate a new doctrine, eventually termed vertical assault, which relied upon rotary-wing aircraft as an alternative to ship-to-shore movement by surface craft. The following year, Marine Corps Schools issued a mimeographed pamphlet entitled, Amphibious OperationsEmployment of Helicopters (Tentative). This 52-page tome was the 31 st school publication on amphibious operations, so it took the short title Phib - Concurrently, the Marine Corps formed a developmental helicopter squadron to test the practicality of Phib - s emerging theories. This formative unit, Colonel Edward C. Dyers Marine Helicopter Squadron 1 (HMX-1), stood up in December 1947 and was collocated with Marine Corps Schools. The new squadrons primary missions were to develop techniques and tactics in conjunction with the ship-to-shore movement of assault troops in amphibious operations, and evaluate a small helicopter as replacement for fixed-wing observation airplanes. Among the officers assigned to HMX-1 was the Marine Corps first officially sanctioned helicopter pilot, Major Armond H. DeLalio, who learned to fly helicopters in 1944 and had overseen the training of the first Marine helicopter pilots as the operations officer of Navy Helicopter Development Squadron VX-3 at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, New Jersey.

In February 1948, the Marine Corps took delivery of its first helicopters when a pair of Sikorsky HO3S-1s arrived at Quantico. These four-seat aircraft featured a narrow greenhouse cabin, an overhead three-blade rotor system, and a long-tail housing that mounted a small vertical and-torque rotor. This basic outline bore such an uncanny resemblance to the Anisoptera subspecies of flying insects that the British dubbed their newly purchased Sikorsky helicopters dragonflies. There was no Service or manufacturers authorized nickname for the HO3S-1, but the most common unofficial American appellations of the day were whirlybirds, flying windmills, and pinwheels. The HO3S-1 had a cruising speed of less than 100 miles per hour, a range of about 80 miles, could lift about 1,000 pounds, and mounted simple instrumentation that limited the HO3S to clear weather and daylight operations. This very restricted flight envelope was acceptable because these first machines were to be used primarily for training and testing. They were, however, sometimes called upon for practical missions as well. In fact, the first operational use of a Marine helicopter occurred when a Quantico based HO3S led a salvage party to an amphibious jeep mired in a nearby swamp.