This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1955 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

TALES OF EDISTO

BY

NELL S. GRAYDON

Photographs by

CARL JULIEN

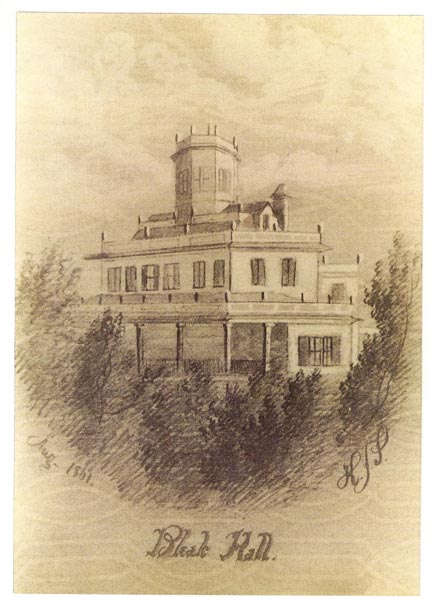

THE GRANDEUR OF EDISTO during the lush days when Sea Island cotton was king is shown in the old print of Bleak Hall, home of the Townsend family for a hundred and fifty years, and the photograph of the approach and formal gardens of Oak Island, one of the Seabrook plantations, here seen shortly after its occupation by Federal troops during the Confederate War.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No book becomes a reality without the aid of a number of people. My thanks are due to Charles E. Lee, editor of the University of South Carolina Press, for his unfailing interest and competent help; to S. L. Latimer, Jr., John A. Montgomery, and Eugene B. Sloan, editors of The State (Columbia, S.C.), for printing my first stories of Edistoan encouragement without which this book would not have been written; to Dr. Anne King Gregorie, editor of the South Carolina Historical Magazine , for her faith when I was doubtful; and to Mrs. J. C. Self, for suggesting the writing of the book.

I am also grateful to those who gave generously of their time and knowledge, helping me to gather material, or giving permission to photograph their homes: Mrs. Helen Grimball Whaley, Mrs. Lucy Whaley Rast (Mrs. J. H.), Mr. and Mrs. Joseph LaRoche Seabrook, Carl Julien, Mr. and Mrs. William E. Seabrook, Miss Henrietta Seabrook, Mrs. Rachel Whaley Hanckel, Mitchell Seabrook, Mrs. Edwin Belser, Mrs. Arthur F. Langley, Mrs. J. S. Seabrook, Dr. and Mrs. John Townsend, John E. Jenkins, Mrs. Edward Jenkins, Judge Marcellus Whaley, Mrs. George Cullen Battle, Mrs. Frank Wilkenson, Mrs. Virginia Griffen Burns, Dr. and Mrs. L. B. Newell, Colonel George Cornish, Mrs. J. P. Abney, Bishop Albert S. Thomas, Mrs. Donald D. Dodge, Mrs. Lee Mikell, Mrs. Julia Mikell LaRoche, Mr. and Mrs. J. G. Murray, Chalmers S. Murray, Mrs. Marion Seabrook Connor (Mrs. Parker), Dr. and Mrs. Jenkins Pope, Admiral and Mrs. C. D. Murphey, Carew Rice, Percival H. Whaley, Mrs. G. W. Seabrook, Mrs. Mamie Johnston Stevens, Mrs. Willie Mikell, and Captain Teddy Bailey.

John Bennett graciously permitted me to reprint his delightful story, Revival Pon Top Edisto. Equally kind were Dr. and Mrs. I. Jenkins Mikell in allowing me to use portions of Rumbling of the Chariot Wheels , by the late Jenkins Mikell. In writing of the churches of the Island, I have relied heavily on the Session Book Minutes of the Presbyterian Church, and for Episcopal history upon the Private Register of Reverend Edward S. Thomas, now in the possession of Bishop Albert S. Thomas. Other material is quoted with the permission of the following newspapers: The State and The State Magazine (Columbia, S.C.), The News and Courier (Charleston, S.C.), The Press and Standard (Walterboro, S.C.), The Baltimore Sun, and The New York Sun (now The New York World-Telegram and Sun ) .

N. S. G.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Seabrook House

Cassina Point

The Episcopal Church

Seaside

The Presbyterian Church

The Presbyterian Parsonage

Windsor

Sunnyside

Middleton

Old House

Brooklands

Prospect Hill

Peters Point

Slave Houses at Cassina Point

Brick House

Mikell Town House

INTRODUCTION

FORTY miles southwest of Charleston, South Carolina, within the arms of two tidal rivers, lies a fabulous Island. An aura of mystic and alluring charm hovers over the Island and its old homes. Weird gray moss shrouds with ghostly grandeur the queenly magnolias and gnarled live oaks around the plantation houses. Yellow jessamine and white Cherokee rose give an eerie loveliness to dark tangled jungles of palmetto and myrtle, yucca and jack vine. Tidal marshes stretch wide and lonely, the swaying gray-green grass hiding from view the twists and turns of salt creeks and inlets.

In the stillness of the early evening, the faint haunting melody of a slave lullaby drifting through the twilight, the galloping of a horse passing by, the echo of a footstep, or the swish of a silken skirt can bring forth half-forgotten memories of long ago. Then, if you have been welcomed into the homes and hearts of the Island, you may hear stories of the people and the land.

In the old days, a tribe of Indians called Edistows pitched their tents on the banks of the North Edisto River and found a paradise in the fertile land with its abundant game. Later, the exploring Spaniards called the Island Oristo, still later it was known as Locke, and some original grants give the title as Mause Island; but for many, many years it has been called Edisto.

Some claim that Edisto was settled before Charleston. Old records tell us that the Earl of Shaftesbury, one of the Lords Proprietors, bought the land about 1674 from the Indians for a piece of cloth, hatchets, beads, and other goods; and we know that soon afterwards Paul Grimball had a home at Point of Pines, where the tabby remains of its foundation can still be seen. About 1682, South Carolinas fifth colonial governor, Joseph Morton, built his handsome house on the Island and brought slaves in large numbers to Edisto. But the Indians and Spaniards made living there hazardous, and in 1686 the Spaniards raided the Island, burned Grimballs and Mortons houses, and carried away loot of great value, including silver and slaves.

The first permanent settlers attempted to grow rice on Edisto, but were unsuccessful because of the lack of fresh-water ponds and suitable land. They then turned to the culture of indigo, for which there was a ready and profitable market in England. But with the beginning of the Revolution, Great Britain cut off the bounty she had been paying on indigo, and its cultivation in South Carolina nearly ceased.

At the close of the eighteenth century, the Edisto Island planters discovered a new source of great wealth in Sea Island cotton. The weed flourished in the Islands black fertile soil and produced a long silky staple with so perfect a texture it was adapted to the most delicate manufacture. In fact, the land produced finer cotton than was made in the Bahamas, from which the first seed for planting in the Sea Islands was procured. It is said that the cotton from the Edisto Island plantations was never put on the market: the mills in France contracted for it before it was put in the ground. Nearly all of the planters made periodic trips abroad and visited the mills using their product. The planters on Edisto experimented with their seed, and after a time each one perfected a jealously guarded strain of his own. It is said that each of them could recognize his own cotton whenever he saw it.