A SPADE AMONG

THE RUSHES

A SPADE AMONG

THE RUSHES

MARGARET LEIGH

First published in 1949 by

Phoenix House Limited

London

This edition first published in 2011 by

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

Copyright Birlinn Publications Limited

All right reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A Catalogue record of this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84158 986 2

Facsimile origination by Brinnoven, Livingston

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI

CONTENTS

Foreword

My father and I crofted in Smirisary at the same time as Margaret Leigh became a crofter in the 1940s. At that time there were four families working the land; they were hard but happy days. Many an hour I spent with Margaret, exchanging stories while herding cattle.

Margaret Leigh was the only crofter in Smirisary with a horse. To the great amusement of the older folk it would not always do as she wanted it to. However, it was a great help to us all when peat had to be brought home.

Margaret very quickly became part of the crofting community and was well thought of. It all seems such a long time ago!

I am 81 years old; I have seen many changes, not least of which is the end of the crofting community as I knew it.

Katy Maclean ne Gillies

Gortean

Smirisary

1996

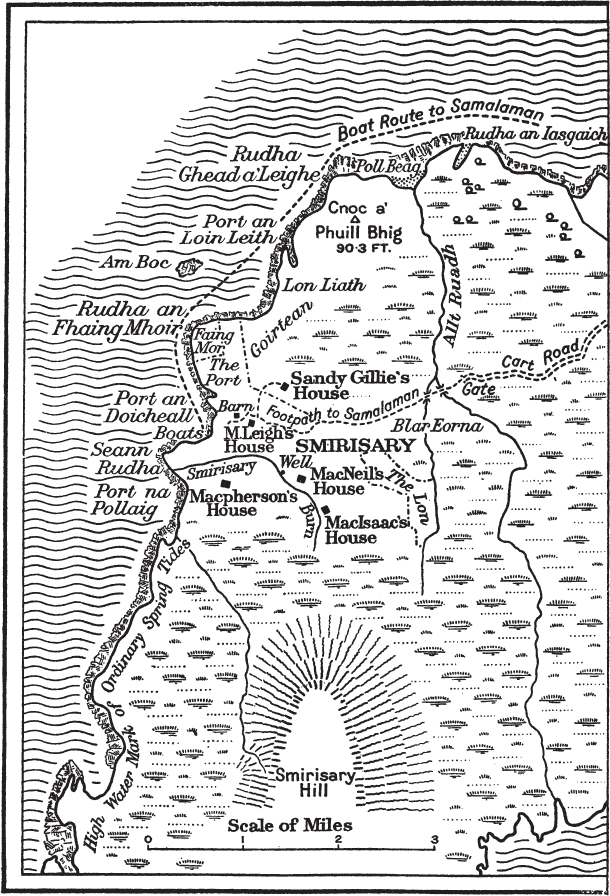

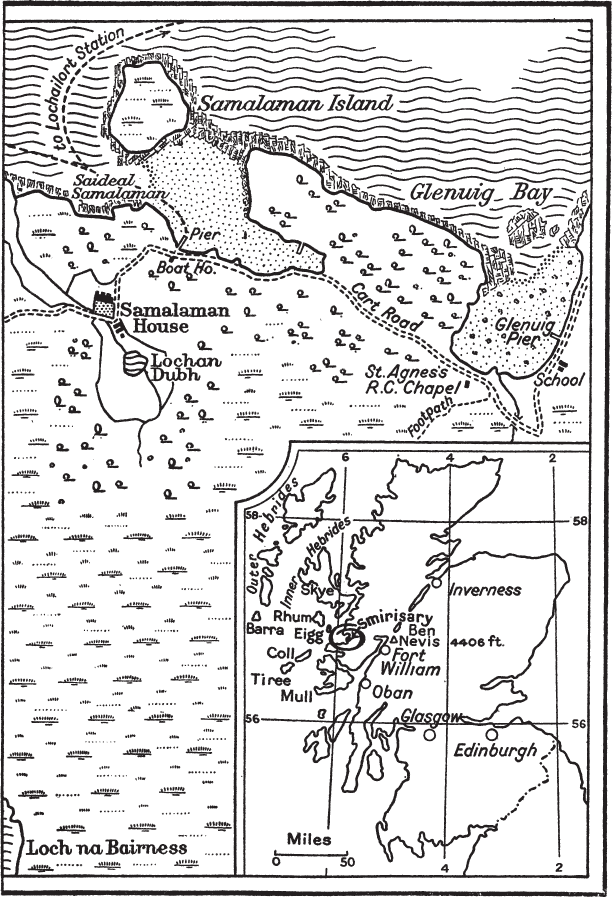

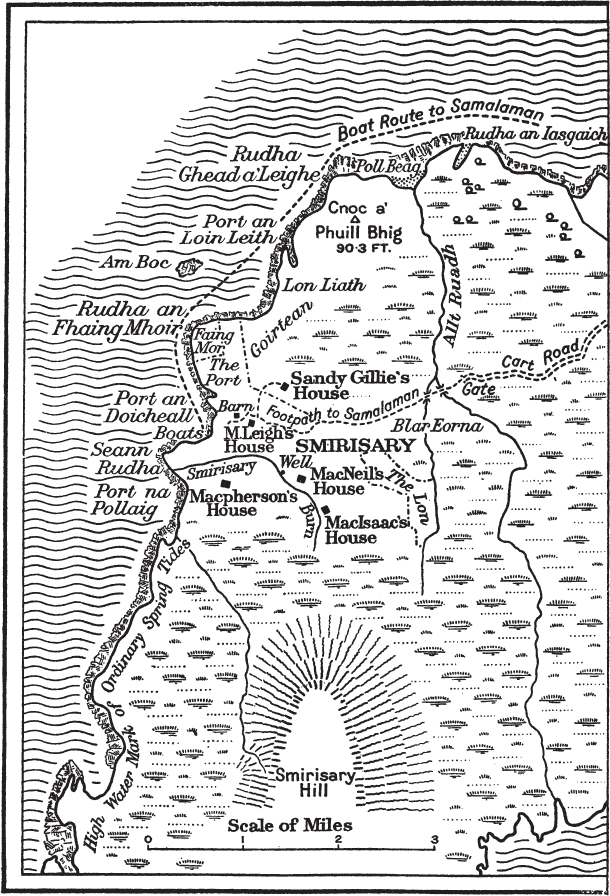

A MAP OF SMIRISARY

CHAPTER

1

I Find Smirisary

I T was in March 1940, that I first set eyes upon Smirisary. My friend Graham Croll had seen it before and told me to be sure to go there as it was the very place that would appeal to me. He was right. I had been too long imprisoned in glens, where leaning hills frowned down on me and took away the winter sun. But Smirisarythe queer name, half Norse, half Gaelic, means butter shielinglay open to the western ocean, and its green crofting land, enamelled with flowers, shone like a jewel, half-ringed by hills of rock and heather. There were boats drawn up on the shore and a few houses with byres and barns scattered round the edge of the arable, all stone and nearly all thatched: enough to banish loneliness without destroying privacy. And in the midst a burn, sliding between its deeply eroded banks, too small to raise its voice against the sea. The township of five households was sheltered from the east by high braes, always steep, in places sheer, with tracks leading to more arable above and the great world beyond. There were men herding cows in little groups or vanishing over the pass with creels to the distant peat moss. Upon the burden of the surf was thrown the pattern of other soundsa collie barking, a cock crowing, the brush of wind in withered bent and heather, the grinding of keel on shingle. Thus I found Smirisary, and even on that raw March day of wind and chilly showers, I fell in love with it. And having now lived there for four years and seen it at all seasons and in every kind of weather; and having done and suffered all sorts of things in itpleasant, laborious, ridiculous, incredible, but never for a moment boringI find myself more in love with it than ever.

Slithering down the precipitous footpath, I passed the back of the house in which I now live. The walls were of solid, squared stone, excellently wrought, the work of a mason building for himself. But the place had stood empty for twelve years, and the galvanised iron roof was perishing for lack of paint and gaping at the ridge, so that rain seeped down upon the rotting boards of the floor. Nothing had been removed from the interior; the door was intact and bolted, the window panes unbroken, the partitions standing. Pressing my nose against the dusty glass, I could see that there were two large rooms and one small one. It came to me that the house, if repaired, would make an attractive home; but so have I said of a dozen derelict cottages seen in my wanderings, and I thought no more about it. The thing that impressed me most was a pillar of dressed stone, surmounted by a pyramid of the same material, on which a gate had once hung. The gate was gone, and the pillar leaned at a rakish and dangerous angle in a wilderness of nettles; but it gave to the house an exotic distinction it has never quite lost. I passed through a little field full of rushes and the rustling ghosts of last years thistles and burdocks, and across the burn to Annie Macphersons house where Graham had told me to call. She stood at the door, a thin upright figure, watching the stranger approach, and Angus and her brother lingered on the byre path, also at gaze. I greeted him, and he replied in the formal careful English of a habitual Gaelic speaker. Little did I think that in three years time we should be chattering in the old language as we spread dung or turned hay.

I was sufficiently interested in Smirisary to write to the owner of the estate, asking to whom the empty house belonged. But I heard no more, and it appeared afterwards that he had never received my letter. An enquiry sent elsewhere went also unanswered: the house was clearly not for me, and I let the matter drop. In any case I was deep in war-time farm work in Ross-shire and the monstrous threat of that summer made the Smirisary planif plan it could be calledseem only one more of the impossible, visionary things we were going to do or have after the war. The remote Highlands were buzzing with every kind of scareabout invasion, about parachute landings, about the billeting of evacuees and of soldiers. At Fernaig, our energies were bent on food production and we thought of little else.

In December 1940, when my services on the farm were for the moment not required, I went to Barra for several weeks and wrote the greater part of Driftwood and Tangle. I had a furnished cottage, in which I lived with only a dog for company. Later, when I had returned to Fernaig for the spring work, I heard that the cottage was for sale, and nearly bought it, though it had not a square yard of land. Then news came in letters about mysterious works within a mile of the place, on which most of the population were employed. An aerodrome, I thought, and withdrew my offer. The flat machairs of the Hebrides are particularly suitable for runways, and my thoughts turned again to rocky Smirisary where there is no level ground. The works proved to be only a radio-location station; but in most ways I was not sorry that the plan had fallen through. Houses and land are scarce in the Outer Islands and should not be appropriated by strangers. It is better to seek a derelict place which nobody wants and put it in order. This, in theory, should arouse no jealousy or resentment, although in practice you may find yourself unpopular, like the man who wins a race with a supposedly dud horse he has picked up cheap.

CHAPTER

2

I Become a Crofter in Smirisary