1

Foreword: Hail and Farewell

CURSED as we are with universal education, there are few people who have not at one time or another dabbled in literature. I am not speaking of professional writers, but of the numerous amateurs who have taken to writing either to fill the leisure of retirement or as a distraction from a business that is too dull, unprofitable, or depressing to claim their whole attention. Even the inarticulate race of farmers has been driven into print by the slump in agriculture, often to find that books pay better than the farm; for the British public, at last repenting of its long neglect of rural problems, seems to have developed an almost passionate interest in the land.

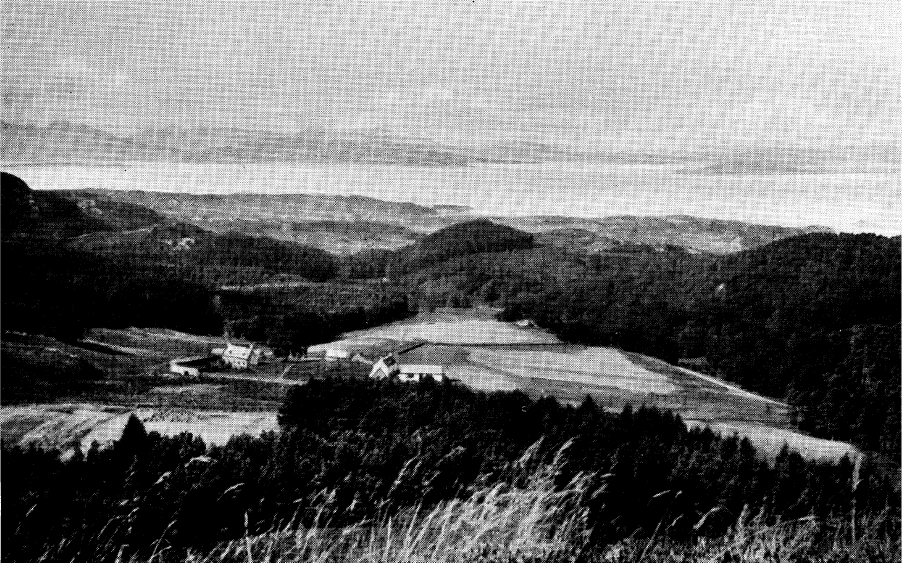

This book is about farming, but not perhaps about the kind of farming that most of us have known, and most certainly not the kind that must (alas for the necessity) prevail in the future. The farm I have called Achnabo is worked very much as it would have been in the days of Abraham. All operations are performed on a small scale and by hand, not for the sake of theory or as an experiment in apostolic simplicity, but because in our special conditions of land, labour, and climate, even a moderately mechanised system of farming would not pay. I have no axe to grind in the matter, and in praise of West Highland methods shall only say that the life, though laborious, is pleasant; and for young people intending to farm, no matter where or how, it provides an unrivalled training in the primitive manual operations on which their mechanical substitutes are based. It is of course possible to work a power loom intelligently without any knowledge of hand-loom weaving it is done every day by thousands of mill-hands; but for a thorough understanding of the whole process of weaving, the man who can operate a handloom is in a greatly superior position.

There has been much discussion of late on the question of preparing boys for the Navy and Merchant Service. Some are in favour of a preliminary training in sail, on the ground that in no other way can resourcefulness and intelligence at sea be so thoroughly developed. Others argue that for boys who will serve on ships propelled by machinery, a training in sail would be an expensive waste of time. It is, however, significant that the Scandinavian countries, renowned in history for their skill in seamanship, have shown most interest in the old tradition, so much so that in Finland no one can qualify as an officer in steam who has not served an apprenticeship in sail. In its constant demand for resourcefulness, initiative, and a skilled weather sense, the primitive unmechanised farm is like a sailing-ship, and no one, I believe, can make proper use of agricultural machinery who has not first mastered the routine of horse and hand cultivation, and studied the habits of plants and animals with a detailed accuracy that is possible only with personal attention and small numbers.

The small hand-worked farm has another advantage it teaches the beginner how to make do with what he has already, or if he must get something new, to contrive it himself out of any odd material lying to hand. A common fault in agricultural education is to provide the student with completely up-to-date, scientific, and fool-proof equipment of a kind that would never be found in practice except on the model farm of a millionaire. The natural result is that the beginner, fresh from his vision of harvest combines and white-tiled dairies, spends much of his working capital on unnecessary improvement of buildings and implements. Every agricultural college should have an improvisation course, with an instructor from the back-blocks of Australia or Canada, who would teach students how to use up the quantities of old iron, wood, bits of wire-netting, and so forth, that lie upon the scrapheap of every farm. If this were done, there would be fewer failures among agricultural students who take up farming on their own account.

I have used the word method once or twice, but the beauty of Highland farming is that there is little or no method about it. This is not quite as feckless as it sounds, for the weather is so variable and the people so indolent that the most sensible and profitable thing is to throw method overboard and swim with the stream. The best-laid plans may be upset by a sudden change in the weather or the non-arrival of an indispensable casual worker, and it seems a waste of time to make them. So this book, like the course of our work on the farm, drifts idly along, following, it is true, the procession of the seasons, but otherwise moving here and there in pursuit of interest, just as a young dog on a walk follows his masters general direction, but continually breaks away to investigate some new and seductive scent.

It is a book written at the kitchen table of a Highland farm, and describing the life that is lived there. But it is not a book about the Highlands. Of these there is an ever-increasing number, some good, some bad, but nearly all well illustrated, and perhaps justified by the beauty and interest of the pictures alone.

The glens and lochs of the north-west have been opened up to a large and intelligent public in the south, which demands topographical books of all kinds, from the chatty guidebook to the technical work on natural history, philology, or folklore. Thousands of people, though they may never have seen them, can distinguish the various peaks of the Cuillins of Skye, can name the varieties of seabirds found on the crags of St Kilda, or of wild flowers blooming on a machair in Uist. They know the meaning of Gaelic place-names, can sing Hebridean songs, are familiar with the ancient legends. A certain amount of this interest in Celtic things is literary or artistic, a transient fashion, sometimes merely a pose. But I am sure that it goes deeper than this.

Some years ago I was told of a London typist who, fired by the works of Fiona Macleod, spent her savings on a visit to Iona, where she was overtaken by the tide and drowned. A silly schoolgirl escapade; and the writer who inspired it is, to my plain Saxon taste, intolerably sentimental. But behind this silliness is the desire, strong and wholly reasonable, to escape from the stultifying bondage of our commercial civilisation. And it is this desire that makes people delight in reading of the wild country that still lies unspoilt, for our pleasure and refreshment, in the far northwest. Changing conditions of life have changed our values. A thousand years ago, the invaders of Britain preferred the flat and fertile south and east, and their choice was a sound one, for a rich living was to be found there. The vanquished were driven into the hills of the Atlantic seaboard, where there was little land worth cultivating. As late as the eighteenth century, Englishmen whose work took them to the Highlands pitied themselves for being condemned to a miserable exile. If they wrote books about the country, they were catalogues of complaints. Now we have changed all that: the horrors of the eighteenth century have become the beauties of the twentieth. No glen is too gloomy for us, no crag too beetling, no loch too grim, no strait too stormy. But if I may digress for a moment, are we sure, when we smile at the miseries of Johnson or Burt, that we are in a position to judge? For us, a visit to Skye means a comfortable journey by corridor train and steamer, or by luxurious car upon tolerably well-made roads, with a good bed at the end of it. No wonder that gloomy Sligachan has lost its terrors, and is no more than a fine piece of scenery to be glanced at with pleasure before ordering our dinner at the hotel. For them, it meant difficult and dangerous travelling on horseback through bogs and thickets, among rocks and precipices, or in small boats, at the mercy of wind and tide, their only shelter whatever hovel they happened to find when darkness overtook them. If at a blow we were to lose every amenity of modern travel, and be condemned to the use of ponies and rowing-boats, our attitude towards the sublime in scenery would, I feel sure, be rather different.