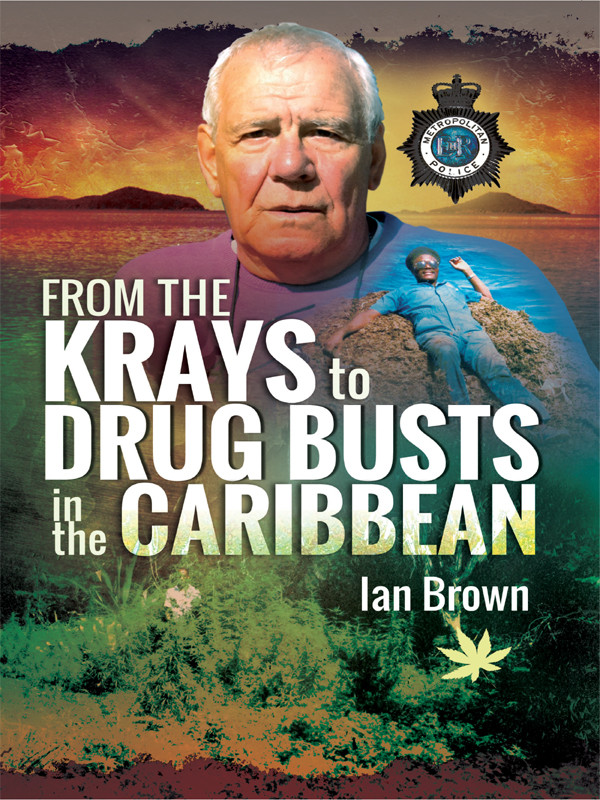

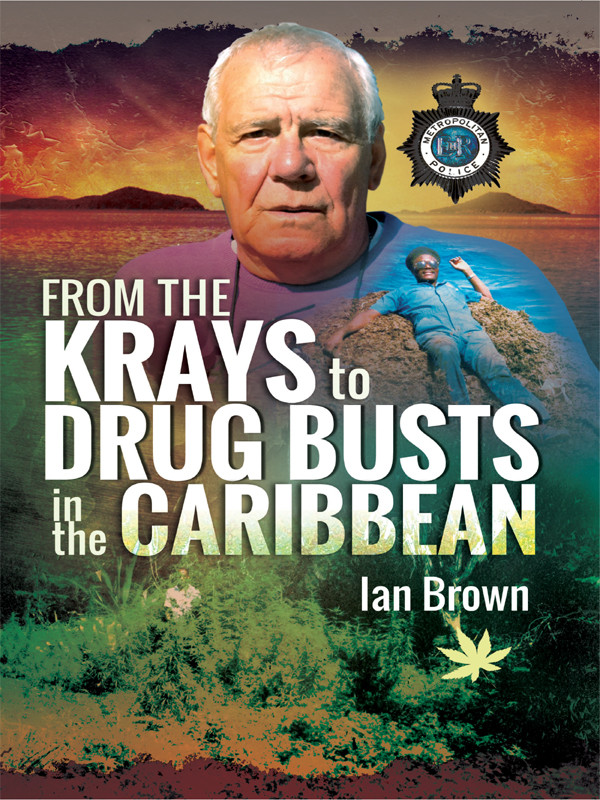

From the Krays to Drug Busts in the Caribbean

To my family, Beth, Mandy, Ross,

Katharina, Ellie and Joe for

making me, me.

From the Krays to Drug Busts in the Caribbean

A Thirty-Year Journey

Ian Brown

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword True Crime,

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Ian Brown 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 750 5

eISBN 978 1 52670 752 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 751 2

The right of Ian Brown to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Chapter 1 The Day the Roof Fell In

Chapter 2 All At Sea

Chapter 3 The Beginning of my Police Career

Chapter 4 The Hither Green Rail Disaster

Chapter 5 Plain Clothes Calling

Chapter 6 The Krays

Chapter 7 The Flying Squad

Chapter 8 Lucky Buggers

Chapter 9 Back To The Sweeney

Chapter 10 Serial Killer Kieran Kelly

Chapter 11 The Brinks-Mat Robbery

Chapter 12 Silence Is Golden

Chapter 13 In The Heat of the Action

Chapter 14 Policing Paradise

Chapter 15 A Drop in the Ocean

Chapter 16 Back Home

Acknowledgements

Im standing in the middle of a dusty Caribbean car park in the blazing sun looking down the barrel of a gun. The man pointing it at me is sitting in a lorry containing fifty million dollars worth of cocaine. It was time to run, and run I did as fast as my ageing legs would carry me before throwing myself into a ditch of stinking water. I lay there for a few moments trying to catch my breath then, coughing and spluttering, I sat up and wondered how the hell did it come to this? I think its time to go home!

Chapter 1

The Day the Roof Fell In

I suppose it all started with an early-morning drive from Keswick to Cockermouth with no cars on the road and scenery that just doesnt get much more beautiful. The sun was just beginning its 3000-foot climb before clearing the summit of Skiddaw, one of the highest points in the Lake District and the panoramic backdrop to the town of Keswick. Darkness had started to fade and the sky showed the first signs of a wonderful pink, clear light. The country road twisted and turned as it followed the shores of Bassenthwaite Lake. The water in the lake, still dark and imposing, would soon become a shimmering mirror reflecting the beauty of the countryside. It is a tourists delight and a photographers dream, but I am neither of these as this is my journey to a much darker place. I am on my way to punch the time clock for the 6.00 am shift before spending eight hours deep in the ground, best part of a mile under the sea, working on the coalface at St Helens Coal Mine in Siddick, Cumberland.

Siddick was not much more than a village with a general store, a butcher, a baker, but no candlestick maker. It had a couple of pubs and terraces of miners cottages all sitting in the shadows of the towering pithead winding gear, which dominated the skyline for miles around.

The mine opened in 1880 and now, in the early 1960s, it was still producing and not yet aware of the impending demise of the coal industry. The whole village was reliant on the mine and local income fluctuated in tandem with the mines prosperity. Its noise was the soundtrack to village life: the whirr of the pithead motors, the blast of the hooter signalling the start and end of each shift, the clatter from the railway as trains arrived to be loaded with the result of the mens labour and the rumble of the lorries, which trundled along the street filling the air with coal dust. But this din wasnt considered an inconvenience to the villagers. In fact, it was a comfort, as it assured them that all was well at the pit, and there would be money in their pockets and purses at the end of the week.

I was employed as a face electrician and on this particular day, halfway through a week of early shifts, everything pointed towards it being just another day at the coalface. The daily routine never varied. I would arrive at our pithead workshop minutes before 6.00 am, punch a time card into the clock and make a cup of tea, before my fellow tradesmen and I donned overalls and helmets, checked the helmet-light battery and set off down the shaft ready to walk almost a mile to the coalface. The walk was always accompanied with the usual banter about football, rugby league, women, sex and the number of pints consumed in the pub the night before. It was also essential to know who had the best sandwiches in their bate box for that day. The older miners reckoned they could tell how long you had been married by the contents of your box and the filling in your sandwich. Their theory was that newlyweds always had the best sandwiches as the wife was still trying to impress the husband. By the time you had been married a few years you were down to dripping on a Monday and homemade jam for the rest of the week. True love was a biscuit or a piece of homemade cake. These men were like fortune tellers reading tea leaves. One quick look in your sandwich box and they would be able to tell you the odds on you winning the football pools, the age, sex and IQ of your children (and if you didnt have any, when they would arrive), whether your wife was pre-menstrual, your sexual prowess and the chances of you getting divorced in the next six months.

As electricians, our main responsibility was to ensure that the machine that extracted the coal from the face (the cutter) continued to work without interruption. Keeping the machine running determined the productivity of the mine and consequently how much cash went in everyones pocket at the end of the week. When the shift was over, it was back to the pithead for a quick shower and then over the road to the pub. Having realized that he couldnt pull pints fast enough to satisfy the thirst of throats dry with coal dust, the landlord of our local hostelry devised a way to ensure the glasses were always full. At the sound of the hooter signalling the end of the shift, he would start pulling beer into an old tin bath placed under the taps and, as the colliers came through the door, he would fill the beer tankards from the bath and line them up along the bar. No payment was asked for or given at this stage as that would be a waste of precious drinking time. A couple of pints later the men would leave their money on the counter, shout abusive farewells to their mates and head off home, where their wives would be expected to be ready with a bowl full of something hot.

Next page