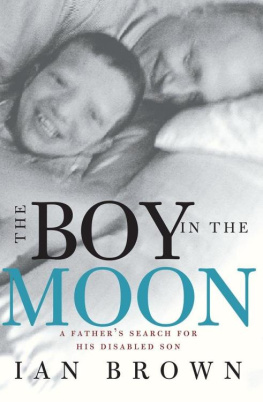

This book is dedicated to

Walker Henry Schneller Brown

and his many, many friends.

What madness came upon you, what daemon

Leaped on your life with heavier

Punishment than a mortal man can bear?

No: I cannot even

Look at you, poor ruined one.

And I would speak, question, ponder,

If I were able. No.

You make me shudder.

SOPHOCLES, Oedipus Rex

I like imbeciles. I like their candour. But, to be

modest, one is always the imbecile of someone.

REN GOSCINNY

one

For the first eight years of Walkers life, every night is the same. The same routine of tiny details, connected in precise order, each mundane, each crucial.

The routine makes the eight years seem long, almost endless, until I try to think about them afterwards, and then eight years evaporate to nothing, because nothing has changed.

Tonight I wake up in the dark to a steady, motorized noise. Something wrong with the water heater. Nnngah . Pause. Nnngah. Nnngah .

But its not the water heater. Its my boy, Walker, grunting as he punches himself in the head, again and again.

He has done this since before he was two. He was born with an impossibly rare genetic mutation, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, a technical name for a mash of symptoms. He is globally delayed and cant speak, so I never know whats wrong. No one does. There are just over a hundred people with CFC around the world. The disorder turns up randomly, a misfire that has no certain cause or roots; doctors call it an orphan syndrome because it seems to come from nowhere.

I count the grunts as I pad my way into his room: one a second. To get him to stop hitting himself, I have to lure him back to sleep, which means taking him downstairs and making him a bottle and bringing him back into bed with me.

That sounds simple enough, doesnt it? But with Walker, everything is complicated. Because of his syndrome, he cant eat solid food by mouth, or swallow easily. Because he cant eat, he takes in formula through the night via a feeding system. The formula runs along a line from a feedbag and a pump on a metal IV stand, through a hole in Walkers sleeper and into a clever-looking permanent valve in his belly, sometimes known as a G-tube, or mickey. To take him out of bed and down to the kitchen to prepare the bottle that will ease him back to sleep, I have to disconnect the line from the mickey. To do this, I first have to turn off the pump (in the dark, so he doesnt wake up completely) and close the feed line. If I dont clamp the line, the sticky formula pours out onto the bed or the floor (the carpet in Walkers room is pale blue: there are patches that feel like the Gobi Desert under my feet, from all the times I have forgotten). To crimp the tube, I thumb a tiny red plastic roller down a slide. (Its my favourite part of the routineone thing, at least, is easy, under my control.) I unzip his one-piece sleeper (Walkers small, and grows so slowly he wears the same sleepers for a year and a half at a time), reach inside to unlock the line from the mickey, pull the line out through the hole in his sleeper and hang it on the IV rack that holds the pump and feedbag. Close the mickey, rezip the sleeper. Then I reach in and lift all 45 pounds of Walker from the depths of the crib. He still sleeps in a crib. Its the only way we can keep him in bed at night. He can do a lot of damage on his own.

This isnt a list of complaints. Theres no point to complaining. As the mother of another CFC child once told me, You do what you have to do. If anything, thats the easy part. The hard part is trying to answer the questions Walker raises in my mind every time I pick him up. What is the value of a life like hisa life lived in the twilight, and often in pain? What is the cost of his life to those around him? We spend a million dollars to save them, a doctor said to me not long ago. But then when theyre discharged, we ignore them. We were sitting in her office, and she was crying. When I asked her why, she said Because I see it all the time.

Sometimes watching Walker is like looking at the moon: you see the face of the man in the moon, yet you know theres actually no man there. But if Walker is so insubstantial, why does he feel so important? What is he trying to show me? All I really want to know is what goes on inside his off-shaped head, in his jumped-up heart. But every time I ask, he somehow persuades me to look into my own.

But there is another complication here. Before I can slip downstairs with Walker for a bottle, the bloom of his diaper pillows up around me. Hes not toilet-trained. Without a new diaper, he wont fall back to sleep and stop smacking his head and ears. And so we detour from the routine of the feeding tube to the routine of the diaper.

I spin 180 degrees to the battered changing table, wondering, as I do every time, how this will work when hes twenty and Im sixty. The trick is to pin his arms to keep him from whacking himself. But how do you change a 45-pound boys brimming diaper while immobilizing both his hands so he doesnt bang his head or (even worse) reach down to scratch his tiny, plum-like but suddenly liberated backside, thereby smearing excrement everywhere? While at the same time immobilizing his feet, because ditto? You cant let your attention wander for a second. All this is done in the dark as well.

But I have my routine. I hold his left hand with my left hand, and tuck his right hand out of commission under my left armpit. Ive done it so many times, its like walking. I keep his heels out of the disaster zone by using my right elbow to stop his knees from bending, and do all the actual nasty business with my right hand. My wife, Johanna, cant manage this alone any longer and sometimes calls me to help her. I am never charming when she does.

And the change itself: a task to be approached with all the delicacy of a munitions expert in a Bond movie defusing an atomic device. The unfolding and positioning of a new nappy; the signature feel of the scratchy Velcro tabs on the soft paper of the nappy, the disbelief that it will ever hold; the immense, surging relief of finally refastening itwe made it! The world is safe again! The reinsertion of his legs into the sleeper.

Now were ready to head downstairs to make the bottle.

Three flights, taking it in the knees, looking out the landing windows as we go. Hes stirring, so I describe the night to him in a low voice. Theres no moon tonight and its damp for November.

In the kitchen, I perform the bottle ritual. The weightless plastic bottle (the third model we tried before we found one that worked, big enough for his not-so-fine motor skills yet light enough for him to hold), the economy-sized vat of Enfamil (whose bulk alone is discouraging, it implies so much), the tricky one-handed titrating of tiny tablespoon-fuls of Pablum and oatmeal (he aspirates thin fluids; it took us months to find these exact manageable proportions that produced the exact manageable consistency. I have a head full of these numbers: dosages, warm-up times, the frequency of his bowel movements/scratchings/cries/naps). The nightly pang about the fine film of Pablum dust everywhere: Will we ever again have anything like an ordered life? The second pang, of shame, for having such thoughts in the first place. The rummage in the ever-full blue and white dish drainer (were always washing something, a pipette or a syringe or a bottle or a medicine measuring cup) for a nipple (but the right nipple, one whose hole I have enlarged into an X, to let the thickened liquid out) and a plastic nipple cap. Pull the nipple into the cap, the satisfying pop as it slips into place. The gonad-shrinking microwave.

Next page