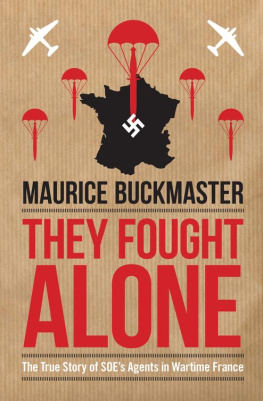

SOE IN FRANCE

1941-1945

An Official Account of the Special Operations Executives British Circuits in France

First produced as The British Circuits in France, 1941-1944

by Major Bourne-Paterson, London, 30 June 1946.

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books, an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS, based on file reference HS 1/122 at The National Archives, Kew and licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Preface Copyright John Grehan

Text alterations and additions Frontline Books

The right of John Grehan to be identified as the author of the preface has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47388-203-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com

email info@frontline-books.com

or write to us at the above address.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in10.5/13.5 Palatino

Preface

By John Grehan

It was more an act of defiance than considered strategic planning when Winston Churchill uttered the oft-quoted phrase to Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare, to Set Europe ablaze. The date was 22 July 1940, just seven weeks after the British Expeditionary Force had been chased off the beaches of Dunkirk and exactly one month after France had signed an armistice with Germany.

The skies over Britain were filled with the drone of German aero engines and the population braced itself for the day Hitlers troops stormed the beaches of the South Coast. Little could either Dalton, Churchill, or even Lord Hankey, who had prepared the ground for sabotage and guerrilla warfare a year earlier, have envisaged in the summer of 1940 just how successful and effective an organisation the newly-formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) would become over the course of the following four years.

From the outset, France was viewed as being the country where the opportunity to develop and support resistance groups would be most likely to succeed. As might be expected, the initial efforts at establishing resistance groups, or circuits as they became called, proved difficult. The apparent strength of the German forces, and Britains comparative weakness, offered little incentive to any French man or woman to risk joining any organisation associated with the latter. Indeed, all of the early circuits were penetrated by the Gestapo, whose brutal methods were rightly feared by the occupied population.

Yet the SOE persisted in infiltrating its agents into France, and, as the war turned increasingly in favour of the Allies, so more French people were encouraged to join the ranks of the resistance movement, in all its forms. As hope of an Allied victory transformed into certainty, so the efforts of the SOE agents and sub-agents grew in scale and audacity, with roads and railways being blocked and blown up, power stations sabotaged, and convoys attacked.

As Allied troops prepared for D-Day in the UK, so SOE planned for the Normandy landings in France. Stock piles of weapons, ammunition and explosives were hidden, orders issued. Even as the great armadas of ships and planes were heading over the Channel on 5 June 1944, across France the resistors began their programme of widespread destruction. Communication lines were cut and means of transportation disrupted, preventing the Germans from mounting a coordinated counter-strike against the Allied beachheads. France at least, had indeed been set ablaze.

The highly secretive nature of the SOE, combined with a somewhat less than methodical approach to record-keeping and the intentional and accidental destruction of a vast quantity of documents, has meant that an accurate assessment of the achievements of the organisation has proven difficult to produce. No doubt well aware of this, Major Bourne-Paterson attempted to record as much about the SOEs British circuits in France as he was able.

A peacetime solicitor, Major Robert Bourne-Paterson became one of the Special Operation Executives planning officers in F Section. His service in this organisation led to his involvement with some of its most famous operatives individuals such as Violet Szarbo GC, whose will he was a witness to. Through his work in compiling this account Bourne-Paterson has been described as being the SOEs first historian.

Bourne-Patersons history is reproduced here in the form that it was originally written. Aside from correcting obvious spelling mistakes or typographical errors, we have strived to keep our edits and alterations to the absolute minimum. A direct consequence of this policy is that there are inconsistencies in the text. The surname Grand-Clment, for example, appears both in this style as well as a single word. Likewise, the accent is often omitted (as is the case in many place names). We have not attempted to correct such errors or standardise the text; that is not the purpose of this book. That said, it is important to point out that a small number of short appendices containing personal information on those who assisted the circuits during the war have been omitted in order to comply with the terms of the Open Government Licence. This detail can of course be viewed by a researcher in an original copy of the report held at The National Archives, Kew.

Such alterations aside, what follows is, in effect, a condensed history of SOEs British circuits in France compiled by a staff officer inside the organisation, and it is reproduced here for the general public for the first time since it was written.

John Grehan

Storrington

July 2016.

Foreword

1. The compilation of the attached notes has been a race against time, and time, regrettably has won. This has meant that certain circuits and a number of very gallant officers have not been mentioned at all and, although I hope and believe that this does not adversely affect the general picture of what the British circuits set out to and did accomplish during the fight for the liberation of France, my apologies are due to them.

2. Another consequence is that this record is not exhaustive. It is not possible to say, because a man or a circuit is not mentioned in these pages, that he or it never existed. Nor must it be assumed, because no Decoration is set against an officers name, that he did not in fact receive one.

3. This subject of Decorations, incidentally, is an extremely sore one in France, where the slowness of the British in awarding Decorations to French members of British circuits is not understood. It is a surprising fact that up to February 1946 no British Decoration had, for instance, been awarded to any member of the