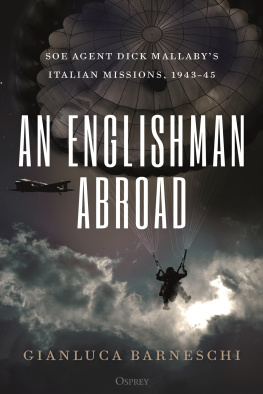

At two minutes past ten on the evening of 13 August 1943, a single British aircraft a four-engined Halifax bomber took off from a desert airfield in Allied-occupied Algeria. At the controls was a Canadian, Alfred Ruttledge, a 29-year-old flight lieutenant with a reputation as a fine pilot, who now set a solitary course across the Mediterranean for enemy territory. Cap Matifou, the last of North Africa, was passed ten minutes later. Menorca was skirted at half past eleven. The les dHyres, off the south coast of France, were reached at one in the morning. Then the Halifax was over Italy.

At two oclock, Ruttledge and his crew picked up in the moonlight a river junction north of Alessandria. Turning for the hills and peaks north of Milan, taking care to stay out of range of the citys anti-aircraft guns, they took a fresh bearing as they recognised Lodi. The Halifax finally reached its target at half past two on the morning of 14 August, when it arrived, growling and low, over Lake Como.

Hidden, fjord-like, in the foothills of the Italian Alps, Lake Como is one of the most striking stretches of water in Europe. Lush wooded slopes drop steeply to the shore. Ochre-roofed villages and villas dot the edge. For centuries it has inspired artists, writers, composers and poets, from Virgil and Pliny to Verdi and Byron. A more charming path was scarce ever travelled than we had along the lake of Como, the poet William Wordsworth wrote to his sister in 1790, recalling hillsides of large sweeping woods of chestnut spotted with villages, some clinging from the summits of the advancing rocks, and others hiding themselves within their recesses. Nor was the surface of the lake less interesting than its shores; part of it glowing with

With the dark mass of Wordsworths summits looming uncomfortably on either side, Ruttledge ran the Halifax down the length of the lake, turned, and returned. Then, as the crews subsequent sortie report records, at 0248 hrs, [on a] bearing [of] 240 [and from a height of] 2,000 ft, a man parachuted from the aircraft straight into the water.

Nestling on Comos banks is the little medieval commune of Carate Urio. It was from here that a baker, Fulvio Borghi, heard the Halifax appear and, in the moonlight, saw the parachute snap open. Borghi hurried to the villages cobbled quay. With him were three other local men Giovanni Abate, who had also heard the plane, Emilio Rusconi and Domenico Taroni and a soldier on sick leave by the name of Morandotti. Taking the oars of a rowing boat, they pushed out onto the lake. Finally they made out in the gloom a figure paddling a small rubber dinghy. They shouted at him to stop. Amico! (Friend!) he shouted back, still paddling.

According to one account of what happened next, the rowers fired a warning shot. The figure stopped paddling. An awkward standoff ensued. The man in the dinghy boldly demanded to know if those shouting and shooting at him were fishermen. When they failed to respond, he put his question again. This time he sounded annoyed. Yes, they said eventually, they were indeed fishermen. And who was he? An Italian, the man replied: an airman who had bailed out of an Italian aircraft. He scrambled aboard their boat and together they made for the shore.

By the time the rowers returned to the quay, the sun was up and a crowd had gathered. One little girl among them was Emilio Rusconis daughter. Sixty-seven years later she recalled the excitement of that curious morning and how, gathered on the road that still overlooks the quay, she and the other children had

Before long he was under guard in the commune offices, his compromising kit having quickly betrayed his claim to be an Italian airman. Beneath a rubber diving suit he wore civilian clothes. Strapped to his leg was a watertight bag, inside which, so the Italian authorities would record, were thousands of Italian lire in L.1000 notes, identity cards and permits, driving licences, and military discharge papers, all perfectly forged, as well as spare parts for a wireless set and cryptographic negatives, all carefully concealed in boxes, [plus] a book entitled Italia mia by Giovanni Papini. Closer inspection of his belongings was to reveal more rolls of money and some photographic negatives concealed in two hollowed-out torch batteries, a wireless aerial disguised as a washing line, and the crystal for a wireless set hidden in the handle of a shaving brush. Pages 185 to 188 of Italia mia were sealed together; when they were sliced open, more negatives were found.

At about this moment the captive declared in fluent Tuscan-accented Italian that he was Lieutenant Richard Norris, a British officer of the Parachute Regiment. Later that day he and his kit were put in a truck and driven along the lake to Como town, the journey apparently preceded by his first beating, this one at the hands of a plume-helmeted officer of the elite Bersaglieri who, unhappy with the prisoners answers, hit him twice in the face. Incarcerated in Como, Norris was soon under the scrutiny of Italian counter-espionage officers. An enemy parachutist has been captured, read a report that evening to the Italian Armys Chief of Staff and the War Ministry in Rome; of British nationality, [he] is wearing civilian clothes and speaks perfect Italian. He is now being interrogated.

Richard Norriss real name was Richard Dallimore-Mallaby. Known to friends as Dick Mallaby, he was a British secret agent. A

Dick Mallaby was a member of a secret British organisation called the Special Operations Executive, the principal Allied force engaged in encouraging resistance inside Italy since Benito Mussolini, the countrys dictator, had declared war on Britain and France in 1940. Today, the public image of SOE is dominated by the work of its agents in Nazi-occupied France, a picture itself distorted by exaggerated claims as to their effectiveness and by a book market unbalanced by stories of the thirty-odd women that it trained and sent in. In fact, from humble beginnings, SOE became active in every theatre of war, dispatching thousands of trained operatives of dozens of nationalities and almost all of them men to harass enemy garrisons, attack important installations, and encourage, arm and fight beside movements as diverse as communist partisans in the Balkans and headhunting tribes in Borneo. What follows is the first full account of SOEs clandestine endeavours at striking at Italy between June 1940, when the Italians entered the Second World War on the side of Nazi Germany, and September 1943, when they finally signed an armistice with the Allies.

Commissioned by the Cabinet Office, this is an official history, the sixth about SOE to be published. The series began

An early case for an official history of SOEs work in Italy was made in Whitehall in 1969. When asked to explore the pros and cons of further volumes to follow Foots, a Foreign Office mandarin, Dame Barbara Salt, herself once a member of SOE, argued that several grounds existed that made Italy worthy of formal attention. One was that it offered an opportunity to highlight unique challenges that SOE had met when getting to grips with Mussolini. Another was that it could permit recognition of the post-armistice exploits of British personnel who had fought side-by-side with Italian partisans in German-occupied Italy.