Fascist Voices

Fascist Voices

An Intimate History of Mussolinis Italy

CHRISTOPHER DUGGAN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Christopher Duggan 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

The Bodley Head

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Duggan, Christopher.

Fascist voices : an intimate history of Mussolinis Italy / Christopher Duggan.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-973078-0

1. ItalyHistory19221945. 2. FascismSocial aspectsItaly.

3. Fascism and the Catholic ChurchItaly. 4. Fascism and cultureItaly.

5. Mussolini, Benito, 18831945Public opinion. I. Title.

DG571.D84 2013

945.091dc23 2012040831

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

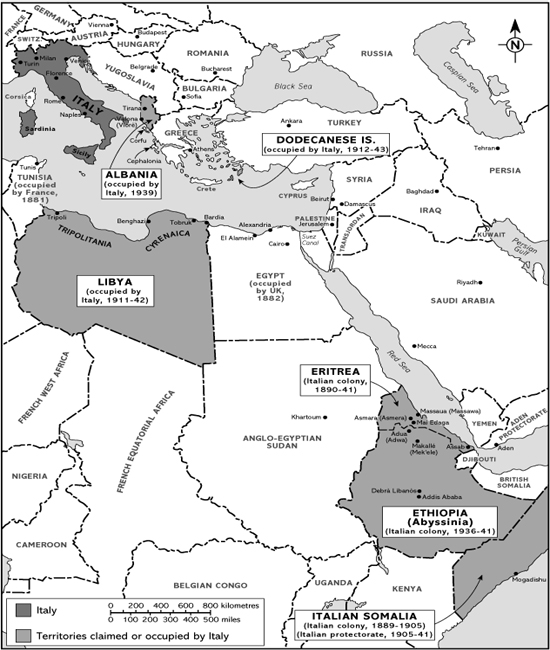

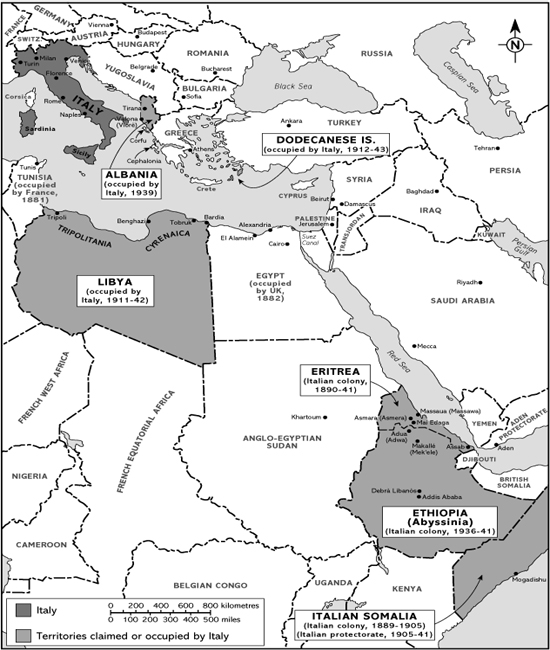

Carlo Ciseri is not a well-known Italian. For most of his long life he worked as a hotel manager in Florence. But to turn the pages of the diary that he kept from 1915 when, still in his teens, he attended military school in Modena, until his last years in a nursing home in the early 1980s, is to have a sense of something remarkable: what it felt like for an ordinary Italian to live through some of the most momentous events in the countrys history. Here, in energetic handwriting, sometimes difficult to read, are the immediate thoughts of a proud ex-serviceman who has just found himself abused and taunted by socialists in a street in Milan in October 1919; a disaffected voter who, having sworn never to get involved in politics again, has heard Mussolini give a speech in March 1920 and been captivated; a confident young husband who has started to feel that the fascist government might restore to Italy the glories and honours of ancient Rome; a patriotic middle-aged man who in December 1935 has donated his and his wifes wedding rings to the nation, with all my heart, in support of the conquest of Ethiopia; and a despondent prisoner of war in a British camp in Kenya who has almost fainted with incredulity upon learning of Mussolinis fall from power in July 1943.

A similar sense of immediacy emerges from the 122 boxes entitled sentimenti per il Duce (feelings for the Duce) that form part of the enormous archive 4,227 boxes in total of Mussolinis private secretariat, the Segreteria particolare del Duce. This office was created to deal with the constant flow of letters that were sent to the fascist leader in Rome around 1,500 a day in the 1930s. The correspondence came from men, women and children of all social classes though it should be remembered that there were still significant levels of illiteracy in Italy at this time, particularly among the poor (on the eve of

Inside the surviving boxes of feelings for the Duce, which date mostly from the later 1930s and early years of the war, are countless telegrams, letters, poems, drawings, paintings and photographs sent by ordinary Italians to Mussolini by way of congratulation, commiseration, thanks, encouragement or entreaty on a wide variety of occasions: following an attempt on his life or on his birthday and saints day; when they wished to make an appointment to see him or after he had delivered an important speech; when a member of his family was ill or when they wanted him to stand as godfather to a new-born child; on a major fascist anniversary or during an international crisis; after they had had an interesting dream or when a husband or son had been killed in action. Partly, perhaps, because they make for somewhat unsettling reading, the contents have not attracted much attention from historians: the now rusty pins and paperclips that hold together the ageing sheets of paper have in most cases remained untouched since they were applied by fascist civil servants over seventy years ago.

The feelings that ordinary people articulated in Mussolinis Italy, and what these feelings might tell us about the appeal or otherwise of the regime, constitute the backbone of Fascist Voices. On one level the book is intended as a broad history of Italy between 1919 and 1945 there is a general framing chronological narrative but it does not set out to be a comprehensive survey of the period. There are many areas that receive little more than summary attention the economy, welfare measures, cultural policies, and sport and leisure, to name but a few. The principal aim is rather to explore how men, women and children experienced and understood the regime in terms of their emotions, ideas, values, practices and expectations. The view from above, constructed largely with hindsight and free from the often disorientating fog of emotion and uncertainty that clouds the normal passage of time, is thus interspersed with perspectives from below making use of private diaries or letters to give a sense of how events were seen at the time. In some places memoirs have been employed, though these lack immediacy and pose questions about the reliability of authorial memory.

A number of the diaries used for this book are published. These include famous works by the likes of the constitutional lawyer and anti-fascist, Piero Calamandrei, the philosopher, Benedetto Croce and the fascist minister, Giuseppe Bottai, and also less well-known journals by such figures as the Padua student, Maria Teresa Rossetti, the Lombard priest, Don Primo Mazzolari, and the young Florentine blackshirt, Mario Piazzesi the only diary of a rank-and-file member of an early fascist squad to have come down to us. However, the great majority of the journals consulted are unpublished manuscripts or transcripts in the Archivio Diaristico Nazionale in the small town of Pieve Santo Stefano in eastern Tuscany and in the Archivio della Scrittura Popolare in Trento. Many of these two hundred or so diaries were written during specific phases in the authors life, such as while serving in the army or being held in a prisoner of war camp, or, more briefly, when on a holiday or conducting a love affair, and contain only fleeting or indirect references to fascism though these can often be revealing.

Next page