First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

P E N & S W O R D M I L I T A R Y

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

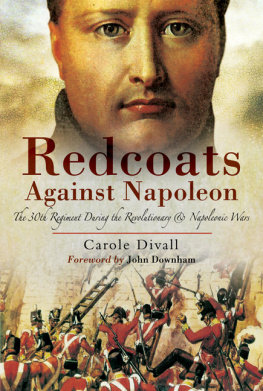

Copyright Ben Hughes, 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-78159-066-9

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-108-7

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47382-992-3

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47383-050-9

The right of Ben Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, HD4 5JL.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Plates

List of Maps

Acknowledgements

This work is the result of two years of primary research. Whilst a considerable amount of previously unused material was unearthed in the British Library, the National Army Museum, the Colindale Newspaper Library and the National Archives in Kew, a limited budget permitted no more than a two-week perusal of the archives in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Because of this, I drew heavily on some excellent secondary sources to flesh out the Spanish side of the conflict. First amongst them was Carlos Roberts Las Invasiones Ingleses, still regarded as the standard history on the subject despite being published over eighty years ago. More recent, specialised histories such as Lyman Johnsons Workshop of Revolution: Plebian Buenos Aires and the Atlantic World and Susan Socrows The Merchants of Buenos Ayres were also helpful. English-language histories are thin on the ground. Ernestina Costas English Invasions of the River Plate is a slim and unambitious volume written from an Argentine point of view as a counter to British ignorance. The only other English-language history is Ian Fletchers The Waters of Oblivion. While providing a much-needed British perspective, it adds little in terms of original research.

I am indebted to Rupert Harding of Pen & Sword Books for taking on this project and John Fletcher of Grenadier Productions and Les Waring for reading and commenting on early drafts. The insight they provided has been invaluable and resulted in several alterations to the text. I would also like to thank my wife, daughter and mother-in-law for excusing me from domestic duties for countless mornings, and especially my most tireless collaborators and proof-readers, my parents Jane and Dave Hughes. It is to them that this book is dedicated.

Prologue

Santo Domingo Church, Buenos Ayres, the Viceroyalty of the River Plate

Midday, 5 July 1807

For Brigadier-General Robert Craufurd, it was the last throw of the die. The Spaniards had his men surrounded. If he failed to unite with the 45th in La Residencia, a fortress-like monastery five blocks to the south, he would have little choice but to surrender. In the last three hours, the church had become a death trap. Cannon and musket fire had shredded the gates, shattered the windows and pockmarked the walls. Filled with gun smoke, the interior resembled an abattoir. Dozens had been killed, a hundred wounded were seeking shelter amongst the overturned pews and several Dominican monks, one of whom had been shot in the chest while trying to prevent the redcoats looting, had been herded together before the altar. The surviving redcoats were returning fire. Outside, elusive targets dressed in improvised uniforms or civilian garb crouched on the rooftops, whilst others sheltered behind barricades erected along the streets. The green-jacketed riflemen occupying the adjacent rooftops and the church tower, from which the British colours still flew, had killed and wounded several. Amongst them was an aide de camp who had had the audacity to demand the British surrender and had been shot through both thighs by Private Thomas Plunkett as a result. Craufurds men were amongst the best soldiers in the world, but the urban environment was a great leveller. The enemy outnumbered them two to one and was determined to defend their town to the last.

Leading the column tasked with linking up with the 45th was one of Craufurds most exceptional officers. Citing a preference for a dashing service over endless drill and a dreary colonial social life, Major William Trotter had given up a staff role at Cape Town to volunteer for the campaign. In October, after sailing across the southern Atlantic, he had led the grenadier company of the 38th across the sand dunes at Maldonado. In February he had been one of the first into the breach at Monte Video and in June he had been wounded fending off a night attack at Colonia del Sacramento. Alongside him were a handful of light infantry, 100 grenadiers of the 45th led by Captain John Payne and the regiments thirty-three-year-old lieutenant-colonel, William Guard.

At one in the afternoon, Trotter formed his men into a compact column, burst out of the church gates and charged down the street. At first the enemy held their fire. When the distance closed, a volley thundered out. The front two ranks of Trotters command were killed or wounded to a man. Lieutenant-Colonel Guards sword was shattered by three musket balls and Captain Payne was shot through the lungs. Trotter was bloodied and had his coat torn to shreds, but pushed on. The Spaniards fell back, but the fire from the windows and rooftops increased. Pausing to look through his telescope at a street corner, Trotter was shot through the head and chest. The survivors hesitated. A few turned back to the church leaving blood trails on the cobblestones as they dragged their wounded behind them. Soon all were in full retreat.

Three blocks to the south, lying squat beside the muddy waters of the River Plate, was the fort of Buenos Ayres. Inside, General Santiago de Liniers was struggling to comprehend what his men were about to achieve. Just three days before, when the Spanish vanguard had been routed on the outskirts of town by Craufurds Light Brigade, the fifty-two-year-old had thought all was lost. Whilst Liniers had spent the night hiding in an outbuilding, the alcalde de primer voto (chief councillor), Martn de lzaga, had taken charge. Mobilising the people with the aid of Bishop Benito Lu y Riegas impassioned rhetoric, lzaga had turned the town centre into a fortress. Trenches had been dug across the main streets, paving stones ripped up and piled into barricades, cannon positioned to cover the major intersections, sharpshooters posted, grenades and incendiary devices made from pitch-filled clay jars handed out to the women and children and arms stockpiled on the towns flat-topped roofs.

Two hours after Trotters death, Brigadier-General Craufurd surrendered. The other British columns taking part in the attack had fared little better: both wings of the 88th had been cut to ribbons; the 5th and 36th had been hemmed in to north of the