Raffles

and the British

Invasion of Java

Tim Hannigan

Contents

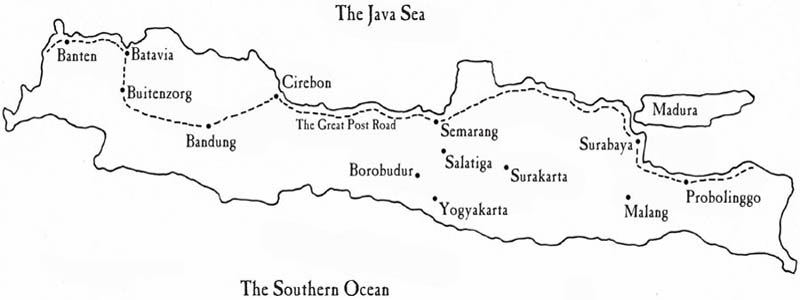

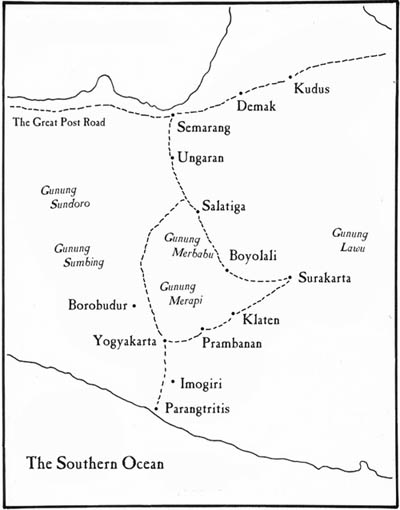

Map of Java 1811-1816

Java 1811-1816

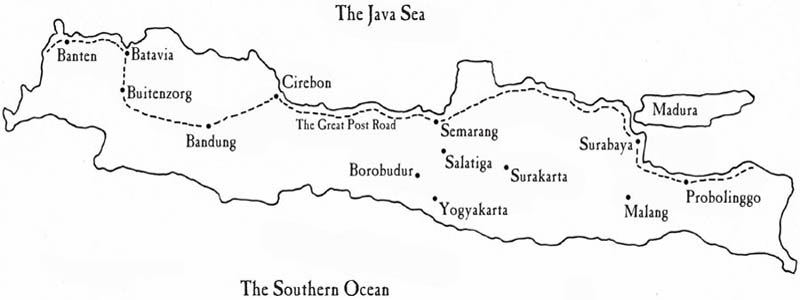

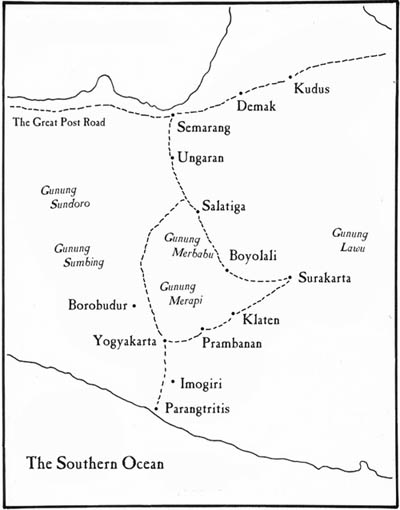

Map of Central Java 1811-1816

CENTRAL JAVA 1811-1816

A Note on Spellings

Modern Indonesian uses a delightfully logical and consistent spelling system, and so I have stuck firmly to Modern Indonesian spellings for the names of places and people throughout this book. The British and Dutch used their own systems of representing local words during their time in Java, and these appear in some of the direct quotations. The colonial version is usually close enough to the modern spelling to need no explanation, but there are a couple of exceptions: Yogyakarta (which is colloquially pronounced and occasionally written as Jogjakarta), was usually written by the British as Djocjocarta, or just Djocjo; the British outpost of Bengkulu in Sumatra was known as Bencoolen.

There is something of an academic convention of writing Javanese words as they should be with an A where the typical pronunciation involves an O. But no one ever spoke or wrote colloquially of a town called Sala or a prince called Dipanegara, so they will appear as Solo and Diponegoro here, and others like them will follow suit.

Glossary

Alun-Alun the great grassy square at the centre of a traditional Javanese city

Babad a Javanese chronicle, usually written in verse in formal language

Bibi an Indian term of address for a woman; in the 18th and early 19th century it was often used by the British in Asia as the term for the native concubine of a European man; the Dutch used the term nyai to the same effect in Indonesia

Candi a Javanese Hindu or Buddhist temple

Dalang the puppet-master in the wayang kulit, and in metaphorical terms anyone who orchestrates events from the background

Djinn an invisible, and often malevolent, spirit. The term is of Arabic origin, and djinns are mentioned in the Koran as beings resembling humans, but made of fire. In many countries, including Indonesia where it is usually spelt jin, the term is used as a more generic catch-all for all sorts of ghoulies, ghosties and things which go bump in the night

Dukun a shaman, witchdoctor or spiritual healer

Dwarapala the monstrous guardian statues that flank entranceways of Javanese temples and palaces as a deterrent to evil spirits

Gamelan Javanese orchestra featuring gongs and xylophones

Haji a Muslim who has completed the Haj pilgrimage to Mecca

Jago a fighting cock, or the head of a rebel band or criminal gang

Jawi the modified Arabic script traditionally used for writing Malay before the 20th century

Joglo a Javanese tiered pyramid roof, traditionally reserved for the homes of royal or noble families, or those of the descendants of the founders of a village

Kampung a settlement or group of houses; in rural terms a hamlet; in an urban setting a quarter

Kawi classical literary Javanese, a language with its own Sanskrit-derived script used for many of the chronicles and epics of old Java

Kebaya a lightweight Indonesian womans blouse, traditionally made of silk or cotton

Klenteng a Chinese temple

Kraton a Javanese palace or royal residence

Kris a ceremonial dagger and essential part of the outfit of a formally attired Javanese man, often an heirloom object, and frequently believed to have magical powers

Kromo High Javanese, the respectful form of the language used for addressing those of superior rank

Memsahib a hybrid Anglo-Indian term for a white woman. Sahib, pronounced saab, is a respectful Indian term for a man in a position of authority; it was given racial connotations when the British misappropriated it and applied it to themselves. They ditched the correct feminine equivalent sahiba and came up with memsahib for their wives

Ngoko Low Javanese, used between equals, or to inferiors

Pasisir literally the Littoral; usually used for the northern coastal regions of Java, and in Javanese terms implying an area outside the cultural and historic heartlands if not beyond the pale, then somewhere very close to it

Patih the prime minister of a Javanese court

Pendopo a traditional Javanese pavilion, usually topped with a joglo roof

Perahu an Indonesian open boat

Peranakan literally descendent, usually used for people of mixed Chinese and Malay or Javanese origins

Pusaka sacred Javanese royal regalia and heirloom items

Ratu Adil The Righteous Prince, a messianic figure in Javanese folklore, first mentioned in the 12th century Joyoboyo Prophecies, set to save the island in times of trouble

Sayyid an Arabic title for a man claiming descent from the Prophet Mohammed

Sajen offerings of flowers, petals and other small items, left at tombs, temples and other places associated with spiritual power

Sepoy an Indian soldier in the army of the British East India Company

Stupa a Buddhist monument

Susuhunan the royal title taken by the kings of Mataram, and retained by the rulers of Surakarta, sometimes abbreviated to sunan. It was originally the title given to the semi-mythical Muslim saints who brought Islam to Java

Tapa Javanese ascetic exercises and meditation, practiced in search of mystical power and enlightenment and ranging from tapa ngalong hanging upside-down from a tree to tapa metak eating nothing but rice for long periods.

Wali Songo The semi-mythical Nine Saints, said to have converted Java to Islam

Wayang Kulit the Javanese shadow-puppet theatre

Introduction: The Past Perfect

It would have been better if we had been colonised by the British, not the Dutch.

I remember very clearly the first time I heard that strange and discomfiting sentiment voiced by an Indonesian. I was sitting at the head of an air-conditioned classroom beneath a whiteboard scrawled with tortuous explanations of the past perfect continuous tense; a callow young English teacher in an oversized shirt and a terrible tie, not long arrived in the seething Javanese city of Surabaya.

This was my favourite class. The other groups I taught were reticent undergraduates or obese infants who fiddled sulkily with their mobile phones throughout their twice-weekly hour of extracurricular English. But this class was different. There were eight of them, senior high school students whose conversational tastes ranged well beyond shopping malls and celebrity gossip. They were clever, boisterous and funny, and they had a talent for leading me down tangents away from tenses. That was what had happened now: we were talking about Indonesian history and politics.

All of them were from the privileged elite of Indonesias second largest city, young men and women bound for Singaporean healthcare and American educations. But they partook with gusto in the peculiar Indonesian pastime of doing down their country in extravagantly hyperbolic terms, bemoaning its corruption and chaos.