Burtyrki Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

THAT OTHERS MAY LIVE

U.S. Air Force Air Rescue in Korea

FORREST L. MARION

That Others May Live was originally published in 2004 by the Air Force History and Museums Program, Washington, D.C.

* * *

This work is respectfully dedicated to the memory

of the late retired Brig.-Gen. Richard T. Kight, USAF,

Commander of the Air Rescue Service between 1946 and 1952, and to all who served in Air Rescue

before and during the Korean War.

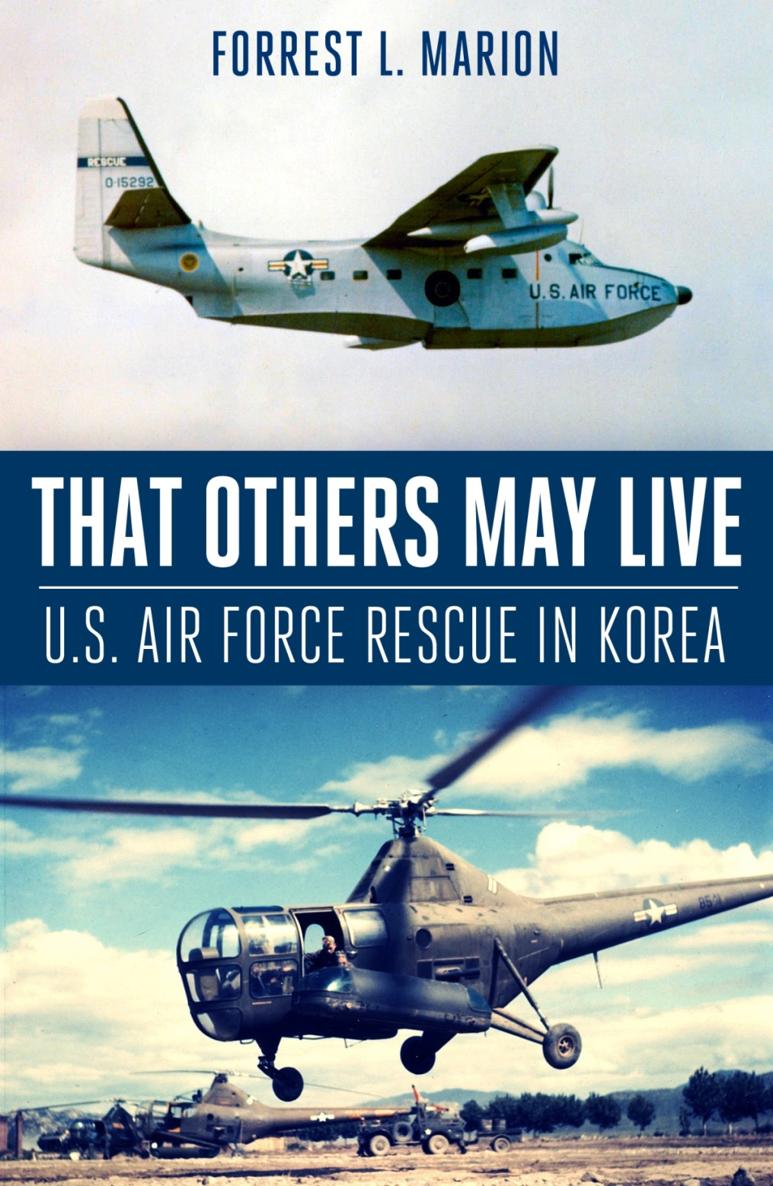

1. Air Rescue Helicopter Combat Operations

Rotary-wing aircraft operations to rescue downed airmen began in the China-Burma-India Theater late in the Second World War when U.S. Army Air Forces emergency rescue squadrons used Sikorsky R-6 helicopters to perform a few dozen pickups. Flying over jungle and mountainous terrain, aircrews returned injured personnel to safety within hours, instead of the days or even weeks that a ground party required. Considering that the first practical rotary-wing aircraft, Igor Sikorskys VS-300, had flown only a few years earlier in 1941, the limited accomplishments of helicopters heralded the birth of a new technology with immense potential for military applications, notably, medical evacuation and aircrew rescue.

Less than five years after World War II ended, a conflict erupted in which helicopters became recognized as indispensable to warfare. Between 1950 and 1953 in the Korean War theater, the Air Rescue Service (ARSvc) operated the SA-16 amphibian, L-5 liaison plane, SC-47 transport, SB-17 and SB-29 bombers, and Sikorsky-built H-5 and H-19 helicopters. Representing technology only a decade old, the lifesaving medical evacuation and rescue achievements of these Sikorsky helicopters captured worldwide attention. Helicopters of all the military services proved their worth throughout the war by evacuating some 25,000 personnel, mostly wounded soldiers, many of whom would not have survived the lengthy, tortuous jeep or truck trip over primitive roads required to reach a hospital. Helicopters of the ARSvcs 3 rd Air Rescue Squadron (ARS) contributed to that record in what was for them a secondary role, evacuating at least 7,000 wounded soldiers over the duration of the conflict. In its primary mission, ARSvc helicopters rescued nearly 1,000 U.S./UN personnel from behind enemy lines.

Although 3 rd ARS helicopters were the only ones among U.S./UN forces with the primary mission of picking up downed airmen, rotary-wing aircraft of other U.S. armed forces performed a limited amount of aircrew rescue work. Marine Observation Squadron Six, which flew the H03S-1, the Marine Corps version of the U.S. Air Forces (USAF) H-5 helicopter, rescued downed airmen and performed medical evacuations, observation and spotting of artillery fire, command and staff flights, and reconnaissance. During late 1950, Marine helicopters rescued at least twenty-three aircrew members from behind enemy lines, while over a slightly longer period, 3 rd ARS helicopters achieved more than seventy-two behind-the-lines pickups. U.S. Navy helicopters, employed primarily in mine sweeping and in observing and spotting naval gunfire, sometimes picked up pilots who had ditched at sea. U.S. Army utility helicopters may also have performed several aircrew rescues.

On June 25, 1950, when North Korea launched a full-scale invasion across the 38 th parallel into the Republic of Korea, elements of 3 rd ARS quickly became involved. On July 7, two L-5 liaison planes and an SC-47 deployed to K-1, the Pusan West Air Base (AB) in Korea, from Ashiya AB, Japan, but they proved unsuitable for operation in the rice-paddy terrain and returned to Japan on July 16. This initial, modest deployment totaling seven men was known as Mercy Mission #1. A second deployment took place a week later when the ARSvc chief, Col. (later, Brig.-Gen.) Richard T. Kight, piloted an SC-47 from Ashiya AB to Korea to escort the first H-5 helicopters into the country. This time, the 3 rd ARS was in Korea to stay. The H-5 outfit, soon known as Detachment F, set up operations at K-2 (Taegu #1), but on August 1 it moved to Pusan as the North Korean offensive threatened the Pusan Perimeter. Four days later, in the first recorded use of an H-5 for medical evacuation, an H-5 transported a wounded U.S. Army soldier, Pfc. Claude C. Crest, Jr., from the Sendang-ni area to an Army hospital. Thousands more evacuations would follow in the three years of fighting that lay ahead. In September, when U.S./UN ground forces broke through the perimeter, Detachment F, now equipped with six H-5s, returned to Taegu. Advanced elements, usually consisting of one L-5 and one or two H-5s, were collocated with Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units, thereby providing H-5 crews the advantages of quick response and proximity to the areas of operation while minimizing any problems caused by communications breakdowns.

3 rd ARS historian 1 st Lt. Edward B. Crevonis summarized the plan for employing the newly arrived H-5s during the summer of 1950 as U.S./UN forces fought desperately to maintain a foothold on the peninsula:

The plan in its original form called for a strip alert helicopter for rescue of airmen to fulfill the primary mission. Rescue would also provide on call aircraft to be used by...front line organizations in evacuation of the most critically wounded....Requests for front line evacuations would all be monitored through the Eighth Army Surgeons office [who]...would determine the priority placed on the specific request. A limited number of aircraft necessitated restricting the requests to only the most critical. The Eighth Army Surgeon was...to have his medical personnel at the scene...evaluate the ground situation for the safest method of approach and evacuation...to decrease the hazard to the helicopters. For rescue of flyers, the T-6 spotter plane [known as Mosquito], who had contact with the fighters or bombers in his area and received all reports of distress or damage, maintained a close contact with his base of operations. When the T-6 ground control received reports necessitating rescue aid, the information was immediately relayed to the [nearest] rescue strip alert helicopter....Requests for rescue of downed airmen were not numerous and a considerable amount of time could be spent flying evacuation missions.