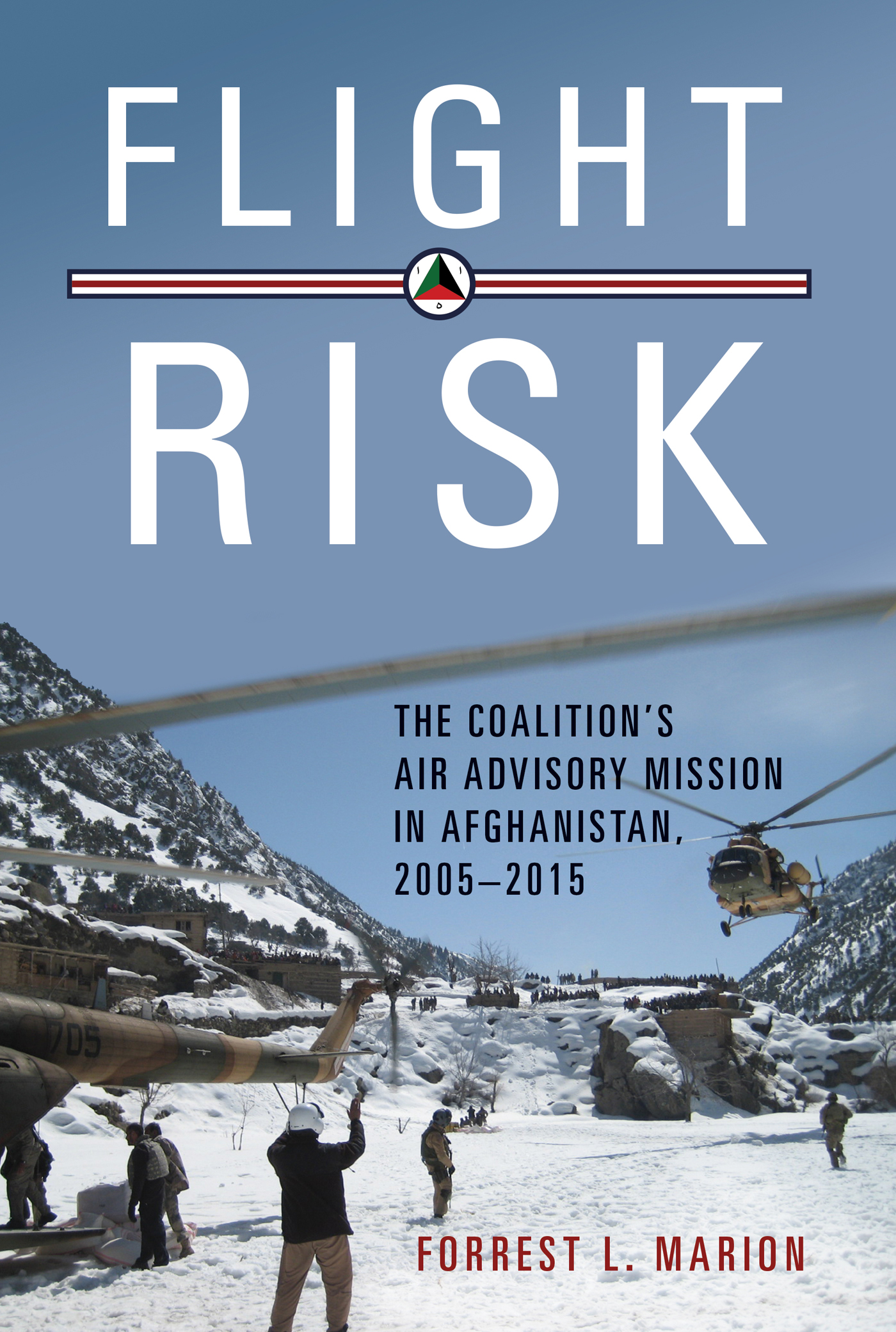

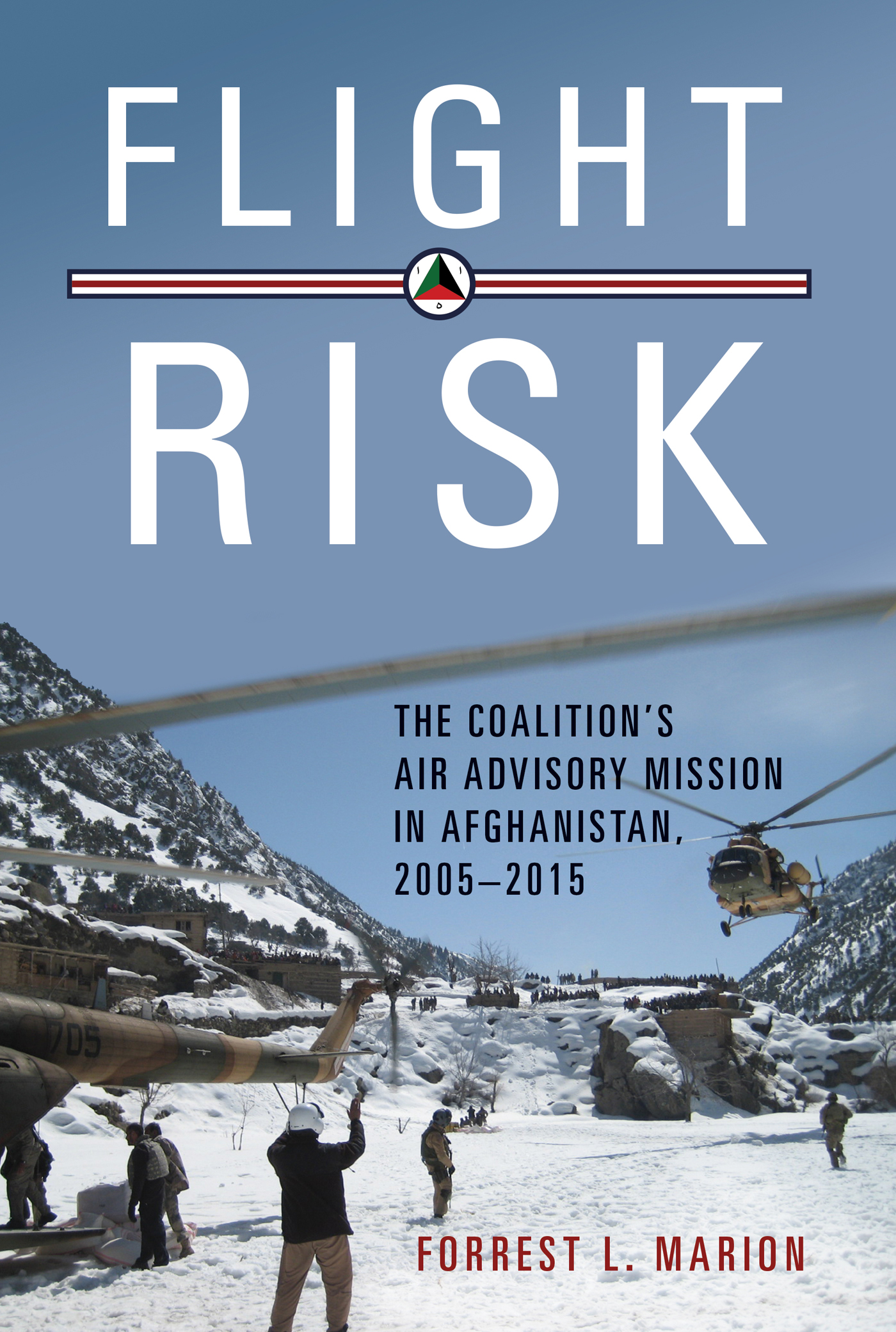

FLIGHT

RISK

TITLES IN THE SERIES

Airpower Reborn: The Strategic Concepts of John Warden and John Boyd

The Bridge to Airpower: Logistics Support for Royal Flying Corps Operations on the Western Front, 191418

Airpower Applied: U.S., NATO, and Israeli Combat Experience

The Origins of American Strategic Bombing Theory

Beyond the Beach: The Allied Air War against France

The Man Who Took the Rap: Sir Robert Brooke-Popham and the Fall of Singapore

THE HISTORY OF MILITARY AVIATION

Paul J. Springer, editor

This series is designed to explore previously ignored facets of the history of airpower. It includes a wide variety of disciplinary approaches, scholarly perspectives, and argumentative styles. Its fundamental goal is to analyze the past, present, and potential future utility of airpower and to enhance our understanding of the changing roles played by aerial assets in the formulation and execution of national military strategies. It encompasses the incredibly diverse roles played by airpower, which include but are not limited to efforts to achieve air superiority; strategic attack; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions; airlift operations; close-air support; and more. Of course, airpower does not exist in a vacuum. There are myriad terrestrial support operations required to make airpower functional, and examinations of these missions is also a goal of this series.

In less than a century, airpower developed from flights measured in minutes to the ability to circumnavigate the globe without landing. Airpower has become the military tool of choice for rapid responses to enemy activity, the primary deterrent to aggression by peer competitors, and a key enabler to military missions on the land and sea. This series provides an opportunity to examine many of the key issues associated with its usage in the past and present, and to influence its development for the future.

FLIGHT

RISK

THE COALITIONS AIR ADVISORY MISSION IN AFGHANISTAN, 20052015

Forrest L. Marion

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2018 by Forrest Marion

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

978-1-68247-336-8 (hardcover)

978-1-68247-361-0 (ebook)

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the United States of America.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the United States of America.

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 189 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

To the air advisors, U.S. and coalition:

All gave some, some gave all.

And in memory of my beloved and beautiful sister,

Kathryn Ann (19622017),

who finished her course well.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Photos

Tables

Maps

FOREWORD

I t has famously been said that Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires, and that assessment is being hotly debated as we continue to experience Americas longest war. The United States entered Afghanistan with pure combat in mind in 2001, but it soon added the role of advisor and mentor to afford Afghanistan the ability to sustain the fight on its own. Almost two decades later, there is scant evidence of Afghanistans ability to defend itself from threats, both external and within its borders.

At issue in Flight Risk is the decision to employ and rely on military advisory missions to prosecute operations in support of counterinsurgency warfare. In examining the air advisory mission of the U.S. Air Force and its coalition allies in Afghanistan, Forrest Mariontwice deployed as historian to cover this missionprovides a focus that has implications far beyond military history. Rather, this work provides a clear picture of the tenuous balance of cultural sensitivity and professional mentorship needed to enable an ally to respond to external threats, fight its internal enemies, and develop an infrastructure for future independence.

Having led a task force to identify and isolate corruption in the almost $7 billion annual contracts in Afghanistan during 2010, I was particularly impressed with Flight Risks unwavering focus on the pernicious influence of corruption, personal and institutional, as well as on the blight of insider attacks in undermining the effectiveness of the overall advisory effort.

Flight Risk will serve as an important reference not only to military historians, but also to those interested in achieving real success in conflict environments where the sustained capability of Americas allies to maintain internal stability is recognized as real strategic success.

Kathleen M. Dussault

Rear Admiral, USN (Ret.)

Henderson, NV

13 October 2017

PREFACE

F rom the middle of January 2009, when I was asked to volunteer for activation as a U.S. Air Force Reserve historical officer and to deploy as the historian to the commanding general, Combined Air Power Transition ForceAfghanistan (CAPTF-A, or CAPTF), the mission grabbed my attention. As a former Air Force helicopter pilot whose adversary aircraft training in the 1980s included the Soviet Mi-8 Hip helicopter, the prospect of providing historical coverage to an outfit flying the Russian-built Mi-17the export version of the Hipwas appealing to say the least. Arriving at the end of February 2009, I doubled as the CAPTFs historian and the initial historian for the 438th Air Expeditionary Wing (438AEW). My boss, then Brig. Gen. Walter D. Givhan, wore two hats as the commander of both entities. As he said, Afghanistan had become the priority, and we must record these events and lessons for posterity or we will break trust with those who follow us. Working for him and his vice commander, Col. Jim Garrett, was a superb experience as the close-knit CAPTF/438AEW air advisor team sought to build air power for Afghanistan. Less than two years later, in early 2011, I deployed again to the same position. By then the air advisor operation had increased in size and numbers of aircraft and was dispersed to more locations around the country. There were both major accomplishments and challenges in the early months of 2011, but 27 April was a day not only of treachery and terrible loss but also of long-term impact regarding the Afghan Air Forces command and control (C2) and the prospects for the AAFs professionalization, as the following chapters suggest.

The first two chapters (19191989, 19902005) provide the background to the studys focus on the air advisor campaign in Afghanistan from 2005 through 2015, a mission continuing through 2017 and perhaps well beyond. While the eight decades preceding 2005 established a pattern of Afghan air powers heavy dependence upon outside assistance, during periods of limited or no foreign aid (the early 1930s, World War II, mid-to-late 1990s) Afghan resourcefulness and perseverance enabled them to continue flying on a small scale. In the wake of the U.S./coalition air campaign that neutralized the Talibans limited air assets in late 2001, a pro-Western Afghan government constituted in 2002 managed to conduct limited flying activities prior to the start of the air advisor work with Afghan airmen. Later, the air advisory campaign plan called for the Afghan Air Force (AAF) to grow to about eight thousand personnel and 150 aircraft by 2016. The Wests objective was that the AAF was to be capable, professional, and sustainable when U.S./coalition advisors and funding were largely withdrawn.

Next page

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the United States of America.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the United States of America.