For Linne Matthews, my editor, who did a great job working on my own most enjoyable writing project.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PEN AND SWORD DISCOVERY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Stephen Wade, 2016

ISBN: 978 147386 354 5

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47386 357 6

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47386 356 9

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47386 355 2

The right of Stephen Wade to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times New Roman by

CHIC GRAPHICS

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Chapter 1

Meet Harry

What was the object of this stupendous voyage? another reason is one with which I fancy most Englishmen will readily sympathize the feat had never before been performed.

Harry de Windt on his book

From Paris to New York by Land

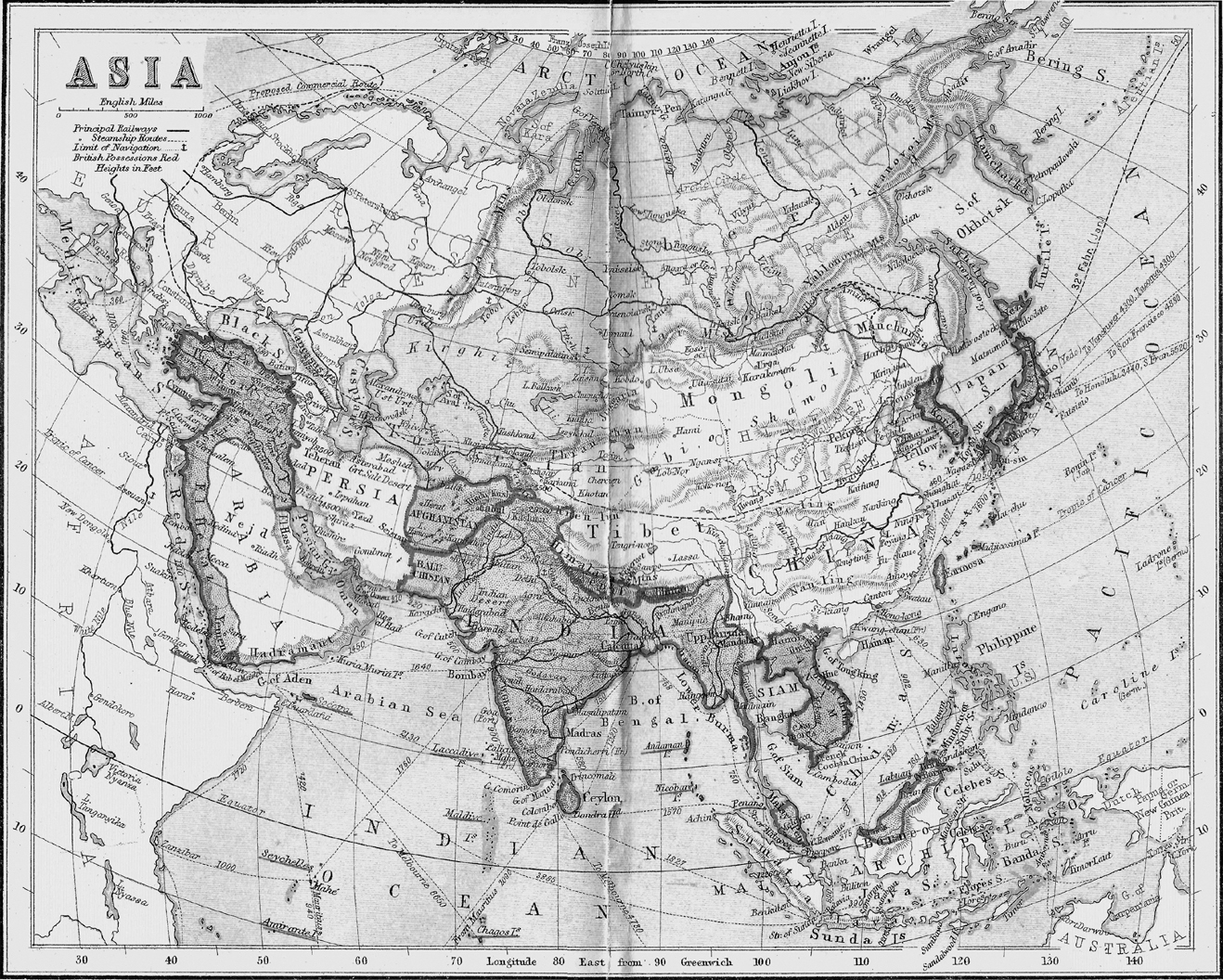

On 12 February 1908, a line of cars were revving up on Broadway, New York, ready for an epic journey to Paris. They were to drive first down to San Francisco, then be shipped to Alaska, and then over the Bering Straits to Siberia. From there the route was overland for thousands of miles to Europe, and finally to Paris. A quarter of a million people lined the New York streets to cheer them. It was to be an arduous, gruelling trek, and the winner was a Protos, driven by Lieutenant Hans Koeppen, who entered Paris on 26 July. The whole affair was a huge celebration of technological prowess, and, of course, human endurance. The media loved it. In a sense, this could not have happened had it not been for one mans seemingly crazed vision of a journey across this vast distance, twenty years earlier. His name was Harry de Windt.

Harry was an obsessive traveller, and getting close to him starts with a simple question: why do people travel? Why, in particular, did so many Victorians travel often to distant and dangerous areas of the globe? The answers were provided by the Vicar of Harrow, as quoted in a work on European travel. He wrote that the great bulk of travellers in his time (c.1850) were motivated by restlessness, by an ill-defined curiosity, by ennui, by the love of dissipation, by a spirit of wandering, by a fancied regard to works of art, by the love of novelty by the superabundance of money. This book is the story of a man who travelled for all these reasons except the fourth, as he always looked down disapprovingly on dissipation. He is Harry de Windt, the Bear Grylls of the 1890s, all-round good sport, and in fact the sort of man you would want on your side if you were in a tight corner.

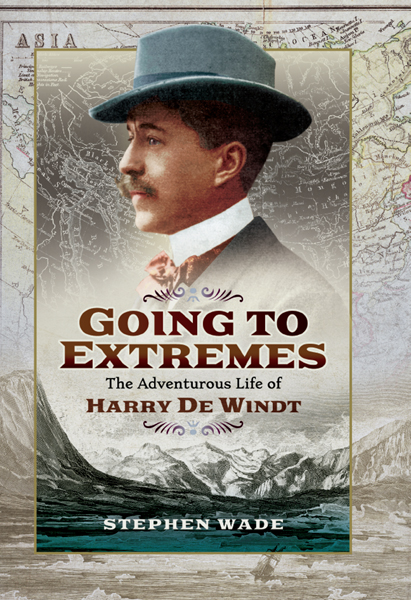

He was a short, wiry man, accustomed to leading rather than following; he could handle a pistol as well as a horsewhip; he could act the playboy in a casino, the jockey in a professional handicap plate, or endure a blizzard in some God-forsaken back of beyond. He remained a gentleman in all situations and expected other men to have the same moral compass. He believed, confirming George Bernard Shaws definition of a gentleman, that he should put more into life than he took out of it. Nevertheless, in between the tough expeditions, he loved his creature comforts.

In an age of literary adventurers and global travellers, he stands out as a Renaissance man. Across the span of his impressive number of books produced both while moving around the world and in between, when he recovered from the privations of his foolhardy treks across barren lands, the reader catches glimpses of this man of tireless energy. One time he is lying in a posting station hut in Siberia, battling frostbite; then he may be seen riding a chaser over fences on an English racecourse; and then perhaps there may be a sight of him lecturing from the platform in America, or having dinner with Teddy Roosevelt. These, when assembled, form a profile of the man known to his contemporaries mainly as the explorer, the wiry little man who had stories of travel spinning from him like a web of constant entertainment. He is at once both a typical Victorian and Edwardian clubman and a whimsical, humorous dilettante, dipping into the occult, palmistry and fringe medicine. There is a Harry de Windt for the reader who loves travel narratives of extreme courage and endurance; a Harry de Windt for the lover of the bon viveur who swapped tales with Oscar Wilde, Arthur Conan Doyle and a host of other celebrities; and a Harry de Windt who could be the man of action, the commandant of a prisoner of war camp in the Great War a man whom one of his charges described as a thin little man who was the very Devil.

Then there is my own Harry: the man who is a gift and a delight for any biographer.

Biography begins with some kind of empathic link between writer and subject, and there is always a first impression that invites the writer to tell the life in focus. Simply, the reason for this, in Harrys case, is the sheer delight of his company. His books particularly his reminiscences are collections of compulsive anecdotes, ranging from momentous meetings with fascinating people to confrontations that bring death perilously close. To settle down in a comfortable chair with any of his books is to accompany a rich, fertile imagination on a long, constantly diverting journey, whether that be by train from Paris to Moscow, or standing with him in sheer boredom waiting for a ticket to cross the Channel as the Great War breaks out all around him.

His portrait in the one book he wrote about his life, in 1913, shows him in evening dress: a full moustache, a stiff, starched high collar, hair immaculately oiled flat, and a bow tie neatly complementing his smart jacket. This is Harry de Windt, known at the time as a traveller. He was a man full of stories. The summaries of his chapters tell it all: My first expedition; a French Don Juan and An interesting blackguard; I meet Madame de Novikoff. A glance at his style reveals the archetypal club raconteur. Here was a man who could entertain, who could project himself to an audience. He was a man who had lived, seen the world, mixed with all classes and all nations. Any London gathering of intellectuals, movers and shakers of the world would have wanted him sat at their tables.

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)