Other Wharncliffe titles by Stephen Wade:

Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in and around Bradford

Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in Grimsby and Cleethorpes

Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in and around Halifax

Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in and around Scunthorpe

The Wharncliffe AZ of Yorkshire Murder

Unsolved Yorkshire Murders

Yorkshires Murderous Women

First Published in Great Britain in 2008 by

Wharncliffe Books

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Stephen Wade 2008

ISBN: 978-1-84563-050-8

Digital Edition ISBN: 978-1-84468-854-8

The right of Stephen Wade to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

Typeset in 11/13pt Plantin by Concept, Huddersfield.

Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Books,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

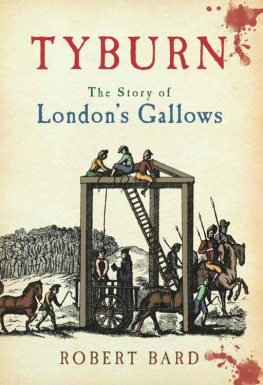

here are many words for this profession: doomster, mate of death, staffman, the topping cove but he is simply the hangman. This was the man who had the resolve and the will to walk on a scaffold with a pinioned man, place a hood on the mans head, slip on a prepared noose so that it knotted at just the right point, perhaps whisper a final word and pull a lever that would send the victim to eternity. When James Berry, from Bradford, applied for the job, he wrote:

here are many words for this profession: doomster, mate of death, staffman, the topping cove but he is simply the hangman. This was the man who had the resolve and the will to walk on a scaffold with a pinioned man, place a hood on the mans head, slip on a prepared noose so that it knotted at just the right point, perhaps whisper a final word and pull a lever that would send the victim to eternity. When James Berry, from Bradford, applied for the job, he wrote:

I beg most respectfully to apply to you, to ask if you will permit me to conduct the execution of the two convicts now lying under sentence of death at Edinburgh. I was very intimate with Mr Marwood and he made me thoroughly acquainted with his system of carrying out his work

It suggests a certain quality of smooth confidence, entirely devoid of defined motivation for doing the work. It could have been a brief to build a new apartment block. Berry noted that he had seen Mr Calcraft execute three persons at Manchester thirteen years ago. The magistrates of Edinburgh must have thought that they had the right kind of obsessive on their hands. For more than a decade he had harboured a wish to do what Calcraft had done, and he had been apprentice to the Lincolnshire man who had studied how to kill by asphyxiation rather than slow strangling.

Yorkshire has had no monopoly of these types, but certainly more than her fair share.

For centuries of English history, men and women were killed by judicial sanction and command, either by hanging or beheading. In some instances there were killings more barbarous than we can imagine today, such as the fact that until the early nineteenth century we had a law on the statute books that meant a wife killing a husband would be burned to death whereas a husband killing a wife would be hanged. Until Sir Robert Peels first spell at the Home Office in the 1820s there were over 200 capital crimes in the criminal law known as the Bloody Code. The deaths of felons on the scaffold meant a major public spectacle, something to rival a popular drama on stage or a bear-baiting contest. Crowds would turn out, some to abuse and revile a murderer and some to hope that the recreant would pray and beg for pardon, make a noble speech and call on his God.

Of course, they would not leap to their deaths and save the state a task: someone had to hang them or behead them, burn them or draw and quarter them. In most cases it was a job for the hangman. From the earliest period, these men were convicts turned executioner to save their skin or to avoid transportation. It was an occupation that existed on the cusp between ghoulish horror and grudging, awesome respect. Some hangmen were to become minor celebrities and earned money lecturing; others wrote memoirs. But on the other hand, many were ruined by drink or took their own lives. The hangman was a figure of dark and menacing myth: a character to frighten children or inhabit a Gothic mystery tale. As the nineteenth century wore on, they became the focus of much media interest, more fascinating to the Victorians as attitudes to hanging changed, moving from public to private after 1868, and always going on while agitators and reformists battled for its abolition. The work of the hangman and the spectacle of the death on the scaffold attracted many famous people: Charles Dickens had a fascination with execution and wrote against its continuance, with fervour and conviction. Thomas Hardy, whose character Tess is hanged at the end of Tess of the DUrbervilles, relished the sight of criminals at the end of a rope and he wrote fiction that involved the myths and superstitions around hanging.

The hangman did a job that very few would even consider doing. Despite the fact that many of them wrote down their reasons for doing that awful duty for the state, the deep motivations in them are still perhaps a mystery. The journalist Robert Patrick Wilson, in his memoirs, writes of a meeting with William Calcraft the Essex hangman in which he is given the simplest but perhaps most tenable reason: that good citizens would all be murdered in their beds if the killers were not removed from existence. Would it were that simple; the truth is that for the century and a half covered by this book, it is certain that several people were hanged for minor thefts; women were hanged and in disgusting legal contexts of failure, insensitivity and bungling; some teenagers were hanged and also some people undoubtedly since proved innocent of the crime.

When Wilson ventured into Newgate, in 1870, he recalled a story that educates us today with regard to the sheer in-humanity of the execution process before the innovations of William Marwood who implemented a more informed method of using the knot and drop distance to make death more speedy. Wilson wrote about a hanging of a man called Jeffreys:

When Jeffreys walked on the scaffold and reached the drop he faced St. Sepulchres church. Calcraft hurriedly and very forcibly turned him round with his back to the church. The awful ceremony occupied a very much longer time than is now taken to bring about death. Calcraft was compelled to walk several yards along the scaffold and return the same way beneath it. All this time the wretched person remained in full view of a densely packed crowd, until with a wild shout from the mob, the condemned dropped

There had been centuries of such bungling, delay and torture, as death was unnecessarily prolonged, with little thought given to the consideration of the convicts situation.

Next page

here are many words for this profession: doomster, mate of death, staffman, the topping cove but he is simply the hangman. This was the man who had the resolve and the will to walk on a scaffold with a pinioned man, place a hood on the mans head, slip on a prepared noose so that it knotted at just the right point, perhaps whisper a final word and pull a lever that would send the victim to eternity. When James Berry, from Bradford, applied for the job, he wrote:

here are many words for this profession: doomster, mate of death, staffman, the topping cove but he is simply the hangman. This was the man who had the resolve and the will to walk on a scaffold with a pinioned man, place a hood on the mans head, slip on a prepared noose so that it knotted at just the right point, perhaps whisper a final word and pull a lever that would send the victim to eternity. When James Berry, from Bradford, applied for the job, he wrote: