This electronic edition published 2013

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Robert Bard 2012, 2013

The right of Robert Bard to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted

or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,

including photocopying and recording, or in any information

storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing

from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-4456-0646-0 (PRINT)

ISBN 978-1-4456-1571-4 (e-BOOK)

Contents

To Mildred Marks

Introduction

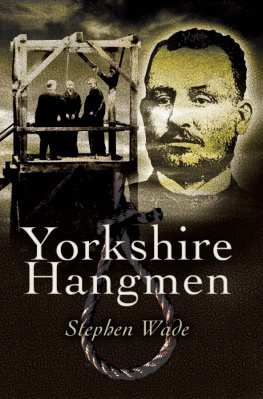

The rope being put about his neck, he is fastened to the fatal tree when a proper time being allowed for prayer and singing a hymn, the cart is withdrawn and the penitent criminal is turned with a cap over his eyes and left hanging half an hourThese executions are always well attended with so great mobbing and impertinences that you ought to be on your guard when curiosity leads you there. (The Foreigners Guide to London, 1740).

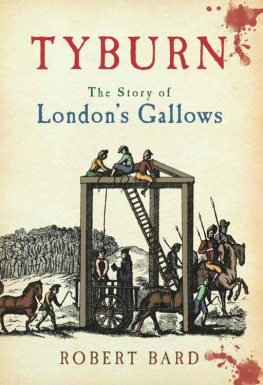

The word Tyburn has been synonymous for centuries with the place near the junction of the Edgware Road and Oxford Street where criminals were executed by hanging. The history of execution at Tyburn is a history of English law, society, power structure, and a mirror to the nature of how crime, often trivial, was dealt with over a period of over 600 years. The gallows, in earliest times, were seen as a symbol of power. Ironically, in a Christian country, abbots fought with other abbots and the monarch for the right to erect gallows in their districts. It has been commented that ecclesiastics, forbidden to shed blood, yet hanged men by the hands of their bailliffs. An abbot, for example, had two parts to fulfil. As an ecclesiastic he gave shelter to thieves, as lord of the manor he hanged them. The same observer comments: the Abbot of Westminster had his servants waiting in Thieving Lane to show thieves the way to sanctuary: on the other hand, he had sixteen gallows in Middlesex alone.

Tyburn was by no means the only site of execution either during these early times or later on. Another early document tells us that the Abbot of Westminster had gallows in Eye [a district of Westminster], Teddington, Knightsbridge, Greenford, Chelsea, Brentford, Paddington, Iveney, Laleham, Hampstead, Ecclesford, Staines, Haliford, Westbourne, and Shepperton. As late as the Rocque maps of London 1746, gallows can be seen in a number of parts of London, including Shepherds Bush Green and Cricklewood. Although Tyburn was one of the primary places of execution between c.1108 and 1783, London and its surrounds was literally littered with gallows. It was common to punish felons by executing them at the scene of their crime. This means that there are very few areas of London which did not at some time play host to an execution. There are numerous accounts dating from the sixteenth century onwards describing Londons solution to political and criminal unsocials. A nineteenth-century writer called London the City of Gallows and remarked that at whatever point you entered London you would have to pass under a line of gibbets. He writes:

Pass up the Thames, there were gibbets along the banks Land at Execution Dock (Wapping), and a gallows was being erected for the punishment of some offender Enter from the west by Oxford-street, and there was the gallows-tree at Tyburn Cross any of the heaths, commons, or forests near London, and you would be startled by the creaking of the chains from which some gibbeted highwayman was dropping piecemeal Nay, the gallows was set up before your own door in every part of the town

Executions in London were popular with the crowd, from the educated to the London mob. Attendance numbers varied, but typically ranged anywhere between 3,000 and 30,000 persons. A particularly notable event could attract up to 100,000 persons. Diaries and letters of prominent persons of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries describe what it was like to attend such an event. Pepys, in his diaries, describes attending a number of executions. His diary of 13 October 1660 describes the execution of the regicide Thomas Harrison at Charing Cross. The execution took place at the southern end of what is now Trafalgar Square, on the same spot where the statue of Charles I on horseback stands, facing down Whitehall. Striking is the casual description of seeing a man undergoing the most barbaric judicial sentence available:

To my Lords in the morning, where I met with Captain Cuttance, but my Lord not being up, I went to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison hanged, drawn, and quartered; which was done there, he looked as cheerful as man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there was great shouts of joy Thus it was by chance to see the King beheaded at White Hall, and to see the first blood shed in revenge for the blood of the King at Charing Cross. From thence to my Lords, and took Captain Cuttance and Mr Sheply to the Sun Tavern, and did give them some oysters within all the afternoon setting up shelves in my study. At night to bed.

Pepys also went to see the death of an acquaintance, Colonel James Turner, but was more concerned about his own discomfort than that of his former friend:

21 January 1664. Up; and after sending my wife to my aunt Wights to get a place to see Turner hanged, I to the office, where we sat all the morning. And at noon, going to the Change and seeing people flock in that, I enquired and found that Turner was not yet hanged; and so I went among them to Leadenhall Street at the end of Lyme Street, near where the robbery was done, and so to St Mary Axe, where he lived, and there I got for a shilling to stand upon the wheel of a cart, in great pain, above an hour before the execution was done.

The following century saw Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (171797) attending the execution by beheading of the 4th Earl of Kilmarnock at Tower Hill for high treason. The Jacobite Rebellion of 1746 claimed a number of noble victims. Kilmarnock, it seems, when stepping onto the scaffold and confronting his own waiting coffin, became unnerved. When he knelt on the block, he asked the executioner not to strike until he dropped a handkerchief he was holding in his hand. Walpole comments that Killmarnock was much terrified and testing the block several times knelt down at the block but showed a visible unwillingness to depart taking five minutes to drop the handkerchief. The fondness which many minds feel (or rather felt) for these melancholy sights is thus discussed by James Boswell (174095), lawyer and diarist, and the multi-talented Dr Samuel Johnson (170984): I mentioned to him that I had seen the execution of several convicts at Tyburn two days before, and that none of them seemed to be under any concern. Johnson: Most of them, sir, have never thought at all. Boswell: But is not the fear of death natural to man? Johnson: So much so, sir, that the whole of life is but keeping away the thoughts of it. He then, in a low and earnest tone, talked of his meditating upon the awful hour of his own dissolution, and in what manner he should conduct himself upon that occasion. I know not, said he, whether I should wish to have a friend by me, or have it all between God and myself. Boswell and Johnson look at reasons for attending a hanging in terms of mortality: