THE

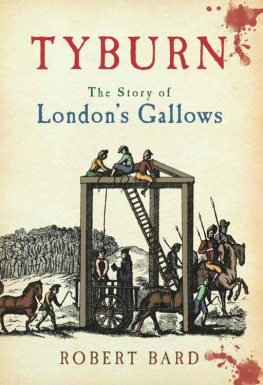

SHADOW OF TYBURN TREE

by

DENNIS WHEATLEY

HUTCHINSON & CO.

CHAPTER I

THE BEST OF FRIENDS

GEORGINA ETHEREDGE'S limpid black eyes looked even larger than usual as, distended in a semi-hypnotic trance, they gazed unwinkingly into a crystal goblet full of water. It stood in the centre of a small buhl table, at the far side of which sat Roger Brook. His firm, well-shaped hands were thrust out from elegant lace ruffles to clasp her beringed fingers on either side of the goblet while, in a low, rich voice, she foretold something of what the future held in store.

She was twenty-one and of a ripe, luscious beauty. Her hair was black, and the dark ringlets that fell in casual artistry about the strong column of her throat shimmered with those warm lights that testify to abounding health; her skin was flawless, her full cheeks were tinted with a naturally high colour; her brow was broad and her chin determined. She was wearing a dress of dark red velvet, the wide sleeves and hem of which were trimmed with bands of sable, and although it was not yet midday the jewels she was wearing would have been counted by most other women sufficient for a presentation at Court.

He was some fifteen months younger, but fully grown and just over six feet tall. His white silk stockings set off well-modelled calves; his hips were narrow, his shoulders broad and his back muscular. There was nothing effeminate about his good looks except the eyes, which were a deep, vivid blue with dark, curling lashes, and they had been the envy of many a woman. His brown hair was brushed in a high roll back from his forehead and tied with a cherry-coloured ribbon at the nape of his neck. His coat, too, was cherry-coloured, with a high double collar edged with gold galloon, and open at the neck displaying the filmy lace of his cravat. His teeth were good; his expression frank and friendly.

They were in Georgina's boudoir at her country home; and, having breakfasted together at eleven o'clock, were passing away the time until the arrival of the guests that she was expecting for the week-end.

So far, the things she had seen in the water-filled goblet had been a little vague and far from satisfactory. For him a heavy loss at cards; concerning her a letter by a foreign hand in which she suspected treachery; for both of them journeys across water, but in two different ships that passed one another in the night..

For a moment she was silent, then she said, "Why, Roger, I see a wedding ring. How prodigious strange. 'Tis the last thing I would have expected. Alack, alack! It fades before I can tell for which of us 'tis intended. But wait; another picture forms. Mayhap we'll learn.... Nay; this has no connection with the last. 'Tis a court of justice. I see a judge upon a bench. He wears a red robe trimmed with ermine and a great, full-bottomed wig. Tis a serious matter that he tries. We are both there in the court and we are both afraidafraid for one another. But which of us is on trial I cannot tell. The court is fadingfading. Now something else is. forming, where before was the stern face of the judge. It begins to solidify. Itit. .. ."

Suddenly Roger felt her fingers stiffen. Next second she had torn them from his grasp and her terrified cry rang through the richly-furnished room.

"No, no! Oh, God; it can't be true! I'll not believe it!"

With a violent gesture she swept the goblet from the table; the water fountained across the flowered Aubusson carpet and the crystal goblet shattered against the leg of a lacquer cabinet. Her eyes staring, her full red lips drawn back displaying her strong white teeth in a Medusa-like grimace, Georgina gave a moan, lurched forward, and buried her face in her hands.

' Roger had started to his feet at her first cry. Swiftly he slipped round the table and placed his hands firmly on her bowed shoulders.

"Georgina! Darling!" he cried anxiously. "What ails thee? In Heaven's name, what dids't thou see?"

As she made no reply he shook her gently; then, parting her dark ringlets he kissed her on the nape of the neck, and murmured, "Come, my precious. Tell me, I beg! What devil's vision was it that has upset thee so?"

" 'Twas'twas a gallows, Roger; a gallows-tree," she stammered, bursting into a flood of tears.

Roger's firm mouth tightened and his blue eyes narrowed in swift resistance to so. terrible an omen; but his face paled slightly. Georgina had inherited the gift of second-sight from her Gipsy mother, and he had known too many of her prophecies come true to take her soothsaying lightly. Yet he managed to keep his voice steady as he said, "Oh come, m'dear. On this occasion your imagination has played you a scurvy trick. You've told me many times that you often see things but for an instant. Like as not it was a signpost that you glimpsed, yet not clearly enough to read the lettering on it."

"Nay!" she exclaimed, choking back her sobs. " 'Twas a gibbet, I tell thee! I saw it so plainly that I could draw the very graining of the wood; andand from it there dangled a noose of rope all ready for a hanging."

A fresh outburst of weeping seized her, so Roger slipped one arm under her knees and the other round her waist, then picked her up from her chair. She was a little above medium height and possessed the bounteous curves considered the high-spot of beauty in the female figure of the eighteenth century, so she was no light weight. But his muscles were hardened with riding and fencing. Without apparent effort he carried her to the leopard-headed, gilt day-bed in the centre of the room, and laid her gently upon its button-spotted yellow satin cushioning.

It was here, in her exotic boudoir reclining gracefully on her day-bed, a vision of warm, self-possessed loveliness, that the rjph and fashionable Lady Etheredge was wont to receive her most favoured visitors and enchant them with her daring wit. But now, she was neither self-possessed nor in a state to bandy trivialities with anyone. Having implicit belief in her uncanny gift, she was still suffering from severe shock, and had become again a very frightened little girl.

Roger fetched her the smelling-salts that she affected, but rarely used in earnest, from a nearby table; then ran into her big bedroom next door, soused his handkerchief from a cut-glass decanter of Eau de Cologne and, running back, spread it as a bandage over her forehead. For a few moments he patted her hands and murmured endearments; then, realising that he could bring her no further comfort till the storm was over, he left her to dab at those heart-wrecking eyes that always seemed to have a faint blue smudge under them, with a wisp of cambric, and walked over to one of the tall windows.

It was a Saturday, and the last day of March in the year 1788., George III, now in the twenty-seventh year of his reign, was King of England, and the younger Pitt, now twenty-eight years of age, had already been his Prime Minister for four and a quarter years. The Opposition, representing the vested interests of the powerful Whig nobles, and led by Charles James Fox, was still formidable; but the formerly almost autocratic King and the brilliant, idealistic, yet hard-headed son of the Great Commoner, with a little give and take on both sides, between them now controlled the destinies of Britain.

The American colonies had been lost to the Mother country just before the younger Pitt came to power. Between the years '78 and '83 Britain had stood alone against a hostile world; striving to retain her fairest possessions in the distant Americas while menaced at home, locked in bitter conflict upon every sea with the united power of France, Spain and the Dutch, and further hampered by the armed neutrality of Russia, Prussia, Denmark, Sweden and Austria also arrayed against her.

Next page