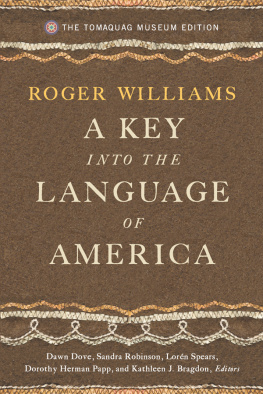

Roger Williams

The Church and the State

Roger Williams

The Church and the State

OTHER BOOKS BY EDMUND S. MORGAN

The Genuine Article: A Historian Looks at Early America

Benjamin Franklin

Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America

The Puritan Family: Religion and Domestic Relations in Seventeenth-Century New England

Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century

The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (with Helen M. Morgan)

The Birth of the Republic

The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop

The Genius of George Washington

The Meaning of Independence: John Adams, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson

The Challenge of the American Revolution

American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia

The Gentle Puritan: A Life of Ezra Stiles

Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea

So What About History

EDITED WORKS

Not Your Usual Founding Father: Selected Readings from Benjamin Franklin

Prologue to Revolution: Sources and Documents on the Stamp Act Crisis

The Diary of Michael Wigglesworth: The Conscience of a Puritan

Puritan Political Ideas

The Founding of Massachusetts: Historians and the Sources

The American Revolution: Two Centuries of Interpretation

Copyright 1967, 2006 by Edmund S. Morgan

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 1987 by arrangement with Harcourt

Brace Jovanovich; reissued 2007

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton 8c Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

Production manager: Devon Zahn

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-25999

ISBN 978-0-393-32383-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London

W1T 3QT

Contents

Did the founding fathers of the United States believe in separation of church and state? Of course. Did they not secure an amendment to their Constitution, stating that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof? Thomas Jefferson declared in 1802 that these words placed a wall of eternal separation between church and state. It is nevertheless fair to ask how high Jefferson and the other founding fathers believed that wall to rise. Not so high as to prevent the early United States House of Representatives from offering its chambers to various denominations of Christians for Sunday services. It did not prevent most of the separate states, in their first constitutions, from restricting political rights (voting and holding office) to Christians or even Protestant Christians. In New England until 1833 state governments levied taxes to pay ministers salaries, by which the populace as a whole were required to support Christianity whether they liked it or not. The United States Army, like the other branches of the military, commissions and pays chaplains of various denominations, without serious questions raised about this particular form of sponsoring religion.

The wall is obviously not impenetrable and never has been. Although in the twentieth century the Supreme Court began closing some of the chinks in that wall, its effectiveness has always depended more on pragmatic exigencies than on the philosophical principles that Jefferson and James Madison sought to place at its foundation. Most of the English colonies in America were founded in the seventeenth century with a single religion as the official faith. But dissent and dissension among the descendants of the first settlers, together with immigration from European countries, produced such a variety of beliefs and churchly institutions that by 1776 no single denomination could command the allegiance of a majority of the citizens of the United States or any of its constituent states. Since no one church could aspire to be the established religion of the Americans, the founders conjured up a wall of separation, however porous, to maintain the peace. As early as 1767 a devout New England clergyman, himself a Congregationalist, could celebrate the existence of an array of churches as a positive virtue: Our grand security, Ezra Stiles wrote, is in the multitude of sects and the public Liberty necessary for them to cohabit together. This and this only will learn us wisdom not to persecute one another.

In this situation the degree of separation between church and state prescribed by the First Amendment was not much more than already existed. There was no real opposition to the amendment, which became law in 1792. But long before the proliferation of sects and denominations, special courage and a special kind of zeal were needed to demand that a government give up the power it derived directly and indirectly from sponsoring the church. In the seventeenth century Roger Williams, a Puritan minister, had both the zeal and the courage, and he had something else, a fertile mind that drove him to examine accepted ideas and carry them to unacceptable conclusions. One conclusion he reached very early was that the welfare of both church and state required an impenetrable barrier between them.

Separation between church and state was seemingly an accepted idea in early New England. The first settlers had gone there to escape the severe penalties that the state imposed on their dissent from a church whose clergy they found too worldly and too inclined to water down religious doctrines. As will be seen in the pages below, they took pains to keep their own governments free from clerical control. But they did not attempt the total separation that Williams came to think was essential to the very being of both institutions.

Williams was not a rebel by nature. Wherever he went people liked him, including the founders of Massachusetts Bay, who welcomed him with open arms when he arrived in 1631. But he was probably the most original thinker to join them and a powerful thinker who could not keep his ideas to himself. It was probably inevitable that men in positions of authority in the Bay Colony would eventually find his ideas concerning the states authority to prescribe religion too dangerous to allow him to remain among them. Five years after he came to Massachusetts they expelled him. He went to Rhode Island, still a wilderness, and established there a haven for other original thinkers, with a government committed to keeping its hands off any churches that people there might gather.

This book is not about Roger Williams as the founder of Rhode Island. It is an attempt to reconstruct his journey from acceptable to unacceptable ideas, from the ideas he shared with other New England ministers to new intellectual territory where they would not or dared not follow him. It is not simply about the wall he would have built between church and state, but about the development of his understanding of what the church is or should be and what the state is or should be. His thinking on these subjects, too disturbing for seventeenth-century Massachusetts, still has the power to disturb twenty-first-century America. It poses a challenge to all those who would allow a church to meddle in politics and equally to those who would allow the state to meddle with the teachings of a church.

Next page