R OGER W ILLIAMS

and

THE C REATION

of the

A MERICAN S OUL

ALSO BY JOHN M. BARRY

The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History

Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927

and How It Changed America

Power Plays: Politics, Football, and Other Blood Sports

The Transformed Cell: Unlocking the Mysteries of Cancer

with Steven Rosenberg

The Ambition and the Power: A True Story of Washington

R OGER W ILLIAMS

and

THE C REATION

of the

A MERICAN S OUL

Church, State, and the Birth of Liberty

J OHN M . B ARRY

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright John M. Barry, 2012

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Barry, John M., ____.

Roger Williams and the creation of the American soul : church, state, and the birth of liberty / John M. Barry.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

EISBN 9781101554265

1. Williams, Roger, 1604?1683. I. Title.

BX6495.W55B37 2012

974.502092dc23 2011032995

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Carla Bolte

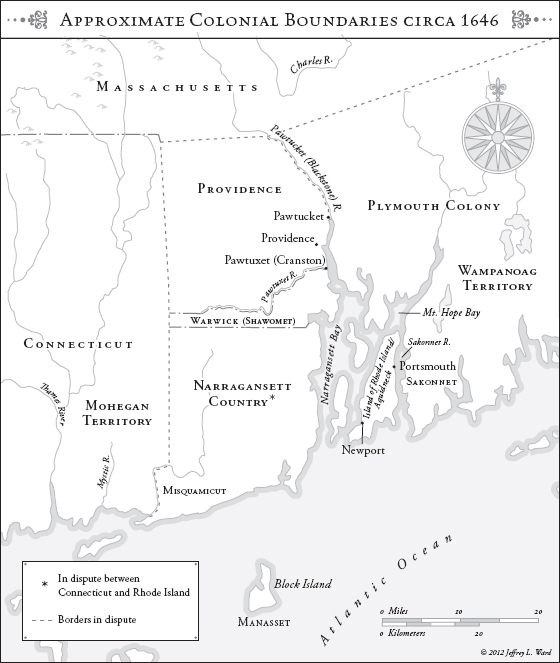

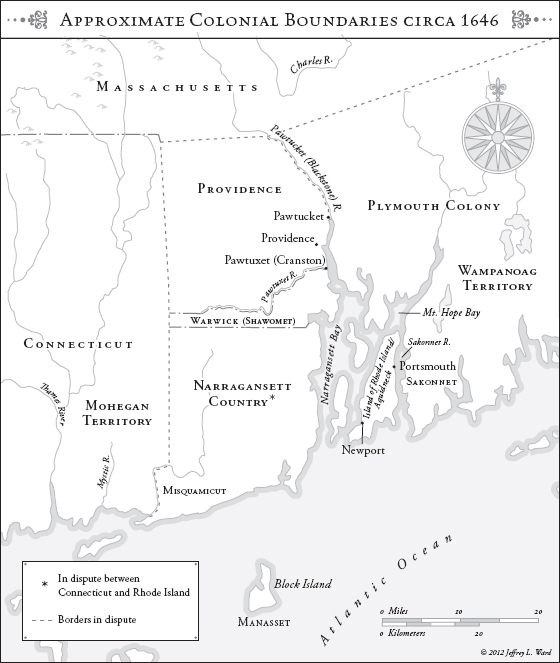

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

To Anne and Rose and Jane and Brown

and Smoke and Dell and E,

and all the others behind the fountain

PROLOGUE

E ven the most bitter accusers of Roger Williams recognized in him that combination of charm, confidence, and intensity which a later age would call charisma. They did not regard such traits as assets, however, for those traits only made him more popular and thus increased the danger of the errors he preached in this, the Massachusetts Bay colony. With such a one as he, they could not compromise.

For Williamss part, neither his benevolent intelligence nor his Christian charity made him willing to compromise either. The error, he believed, was not his, and when convinced he was right he backed away from no one. His mentor Sir Edward Coke, once chief justice of England and arguably the greatest jurist in English history, had taught him that; when King James had declared himself ruler by divine right and above the law, Coke had contradicted him to his face. For that, the king had rewarded him with rooms in the Tower of London.

That precedent made the conflict between Williams and his accusers inevitable and thickened it with history, a history that stretched back long before Cokes defiance. And if the conflict began far distant in both space and time from Massachusetts, crossing both an ocean and centuries, it first came to a head there, in the cold New England winter of 1636. Its repercussions would be immense.

The Massachusetts authorities and Williams would have it out over their great dispute, but they would not settle it, nor is it settled now. For their dispute defined for the first time two fault lines that have run continuously through four hundred years of American history, fault lines which remain central to defining the essential nature of the United States of America today.

The first was the more obvious: the proper relation between what man has made of Godthe churchand the state. The second was the more subtle: the proper relation between a free individual and the statethe shape of liberty, the form American individualism would take. What Williams had largely already learned in England would lead him to prophesy the former; what happened to him that winter and after would lead him to articulate the latter.

N o conflict was anticipated when Williams first arrived in Boston in January 1631 aboard the Lyon, a vessel which carried far more than him and a few other passengers. Its captain, William Peirce, had sailed in dead winter, the worst and rarest time to cross the North Atlantic, to keep a promise.

Less than a year earlier a fleet had carried nearly one thousand men and women to Massachusetts. They were not adventurers. They were like-minded Puritans who considered themselves loyal to the Church of England but disgusted with what they regarded as its corrupt practices, yet the crown and that church were putting intense pressure on them to conform to those practices. To escape that pressure, traveling as whole families and often with their neighbors, they had removed themselves from England and, with determination and purpose, had planted themselves in the wild that was America. As they embarked from England, Governor John Winthrop had reminded them of that purpose, stating that they would plant a citty upon a hill dedicated to God, obeying Gods laws, and flourishing in Gods image.

But they did not flourish and God did not bless them. Indeed, within a few months roughly a quarter of the entire population had died or was dying, starvation threatened the rest, many were fleeing back to England, and nearly all wondered if they had done right.

Anticipating that winter would utterly exhaust their resources, Winthrop had months earlier charged Peirce with resupplying the plantation. Peirces return brought more than food, supplies, or even hope; he brought deliverance and, seemingly, a sign that the settlers had done right in leaving England, a sign that God had used the hard times merely to test the settlers resolve. As the

Next page

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE