This edition is published by Papamoa Presswww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

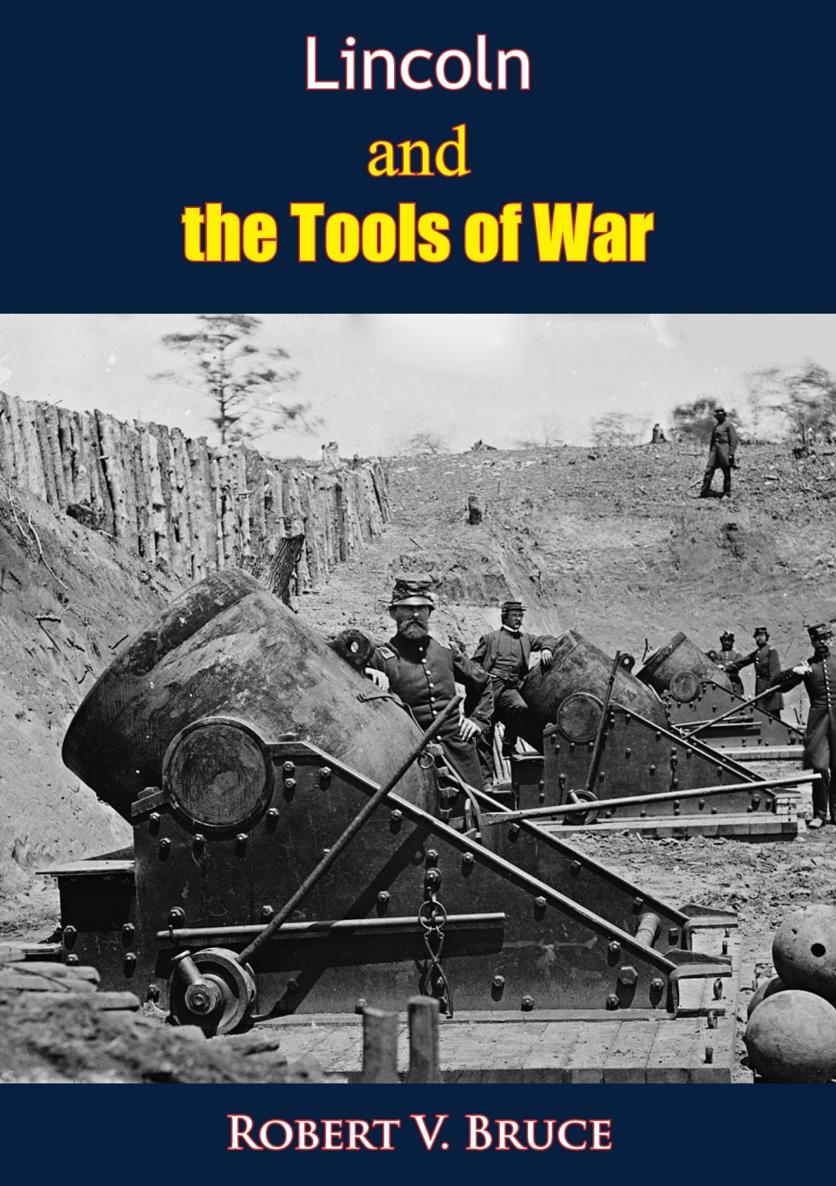

LINCOLN AND THE TOOLS OF WAR

BY

ROBERT V. BRUCE

Foreword by Benjamin P. Thomas

Lincoln and the Tools of War

FOREWORD

BEHIND the solemn, furrowed countenance of Abraham Lincoln was an inquisitive mind. It ranged over the abstract and the infinite, the absolute and the immediate. It was philosophical, and at the same time intensely practical.

On the practical level Lincolns curiosity directed itself, among other things, to mechanical devices. A fellow lawyer remembered that whenever Lincoln encountered a new piece of farm machinery on his rounds of the old Eighth Circuit, he would carefully examine it all over, first generally and then critically; he would sight it to determine if it was straight or warped; if he could make a practical test of it, he would do that; he would turn it over or around and stoop down, or lie down, if necessary, to look under it; he would examine it closely, then stand off and examine it at a little distance; he would shake it, lift it, roll it about, up-end it, overset it, and thus ascertain every quality and utility which inhered in it, so far as acute and patient investigation could do it.

As a young man seeking to improve his education, Lincoln acquired a fondness for mathematics. The months he spent surveying roads, bounding farms and platting town sites taught him to respect the exactness and precision of the trained engineer. His taste for mechanics carried over into the law, making him proficient in handling patent cases. He took out a patent of his own on a device for lifting vessels over shoals. He prepared and delivered a lecture on Discoveries and Inventions. Living on the periphery of the machine age in America, he was keenly aware of the technological advances that were taking place about him. He pondered on the impact of those advances on mankind.

The war came, and Lincoln the President, in whatever time he could spare from other duties, turned his mechanical bent to the improvement of the tools of war. The subject, though touched upon by students, has never been adequately explored. In developing it fully, Robert V. Bruce has written an original and exciting book, one which probes new recesses of Lincolns mind and personality. And there is a great deal more to the story than has been supposed.

Seldom do author and subject mesh so perfectly, for Bruce combines a sure grasp of history and the demands of historical method with expertness in technology. A New England Yankee, with the Yankees predilection for mechanical contrivances, he originally intended to become an engineer, and studied for two years at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Then war broke out and he was called to military service with the Enlisted Reserve Corps. The army assigned him to the University of New Hampshire, where he acquired a B.S. in mechanical engineering, and then sent him to the Pacific theater with the combat engineers. He had always enjoyed history, sometimes more than engineering, though he regarded it merely as a hobby. Gaining a new perspective in the far reaches of the Pacific, he decided that it was his true interest in life, and determined to make it his profession. At wars end he entered the graduate school at Boston University, where he received an A.M. in history in 1947, and after an interval of teaching, was awarded a Ph.D. in 1953. He is now a member of the history department at that institution.

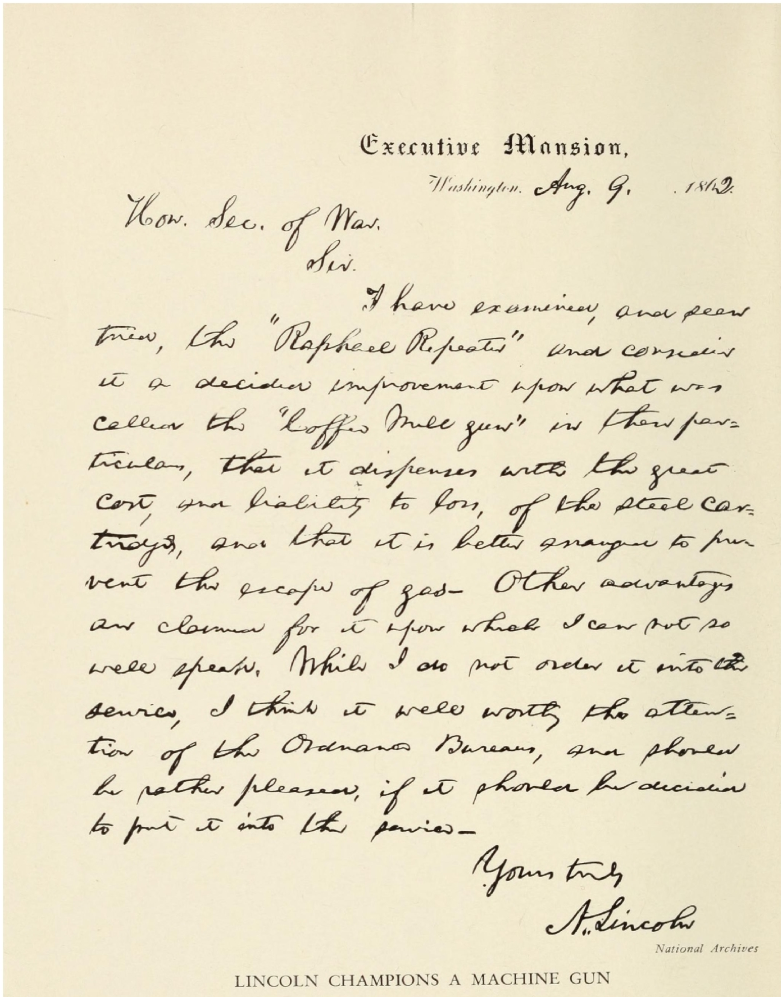

A tireless and enthusiastic researcher, he has ransacked the manuscript collections of the Library of Congress and the National Archives, including the complete Civil War files of both the Army and Navy Ordnance Bureaus, reading hundreds of documents and un-knotting the faded red tape from bundled letters undisturbed for many years. He has used the Robert Todd Lincoln Collection of Abraham Lincolns papers and the recently published Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln , and has turned up some thirty Lincoln notes, letters and endorsements relating to ordnance, which are not included in the Collected Works , He has brought to light an important and hitherto unknown journal kept by Mrs. Gustavus Vasa Fox, wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

The search led him on to other repositories of manuscript material: the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Springfield Armory Library, the New York Public Library, the New York Historical Society and numerous university libraries. Files of yellowing newspapers, obscure magazine articles, bulky congressional documents yielded additional facts. His findings in sum total unveil a new aspect of the Civil War and of Lincolns role as commander in chief.

Eager to utilize the Norths superiority in the mechanical arts as a factor in winning the war, Lincoln made ordnance one of his special concerns during the first two years of his presidency. Thereafter, when it seemed less likely that new devices might be developed quickly enough to affect the outcome of the conflict and with weapons experiments entrusted at last to men of boldness and vision, he devoted less time to the subject, though his vigilance never flagged.

Lincolns interest in new or improved instruments of combat embraced small arms, light and heavy artillery, rockets, projectiles, explosives, flame throwers, submarines, naval armor and mines. He was responsible for introducing machine guns and breech-loading rifles into the Union army. Wishing to render the United States independent of niter from India in the event of war with Great Britain, he bypassed the War and Navy Departments and set up a secret project, under his personal control, to develop a new explosive using a chlorate as a base. He favored the development of rifled cannon. On one occasion he narrowly escaped death or serious injury when an experimental rocket exploded in its launcher while he stood watching nearby.

That many of these devices failed does not mean that Lincoln was naive or absurdly visionary. In many instances he was on the right track but simply ahead of his time. The ideas with which he experimented were often sound, as modern warfare has demonstrated. But only with technological progress would they become practicable.