First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Alan Ogden 2010

ISBN 978 1 84884 248 9

ISBN 9781844685868 (epub)

ISBN 9781844685875 (prc)

The right of Alan Ogden to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Stempel Garamond by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

MPG

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Polliciti Meliora

As one who, gazing at a vista

Of beauty, sees the clouds close in,

And turns his back in sorrow, hearing

The thunderclouds begin,

So we, whose life was all before us,

Our hearts with sunlight filled,

Left in the hills our books and flowers,

Descended and were killed.

Write on the stones no words of sadness

Only the gladness due,

That we, who asked the most of living,

Knew how to give it, too.

Major Frank Thompson (c.1942)

Published with the kind permission of Dorothy Thompson

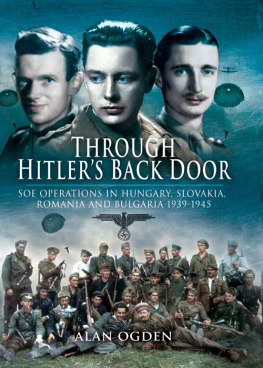

Preface

Historically the business of modern war had been conducted by politicians, diplomats and soldiers, but when on 1 July 1940 the British cabinet approved Winston Churchill's idea for a single sabotage organization called the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an incremental cast of businessmen, bankers, academics, engineers, journalists and adventurers materialized out of nowhere to set Europe blaze and rid it of the Nazi scourge. Nowhere was this more evident than in SOE's Eastern Europe activities, where the line-up of operatives included oilmen, miners, civil servants, chartered accountants, business executives, journalists and a clutch of professional soldiers. The end results of some of their endeavours to set these distant parts of Europe ablaze are still mired in controversy.

Basil Davidson was one such operative. Formerly a journalist, he describes SOE thus in his wartime memoir, Special Operations Europe:

Distrusted by the War Office and deplored by the old pros of secret intelligence, SOE was all the same an extremely English organisation: no other country's rulers, I should think, could ever have evolved it. It was, in short, a triumph of deliberate amateurism. Its uppermost ranks were filled, at this stage almost to a man, by senior businessmen and bankers or others aspiring to be such when the war was over. Now this might be anything but amateurish in terms of economic warfare; if you wanted to know what to do about Romania's oil wells, then call in the men who had managed or financed them. But it was wonderfully amateurish in terms of political warfare. For SOE.'s chief aim and job, more and more after 1940, was promoting armed resistance, a work which took SOE straight into the middle of politics: and politics of a special kind. This was the politics of upheaval and protest, of subversion of conservative order, even of revolution: the kind of politics, in short, that was rightly held in horror by senior businessmen and bankers. They knew absolutely nothing about such matters, having previously regarded them as the business of the police. Now, quite suddenly, they had to act in other countries of course against every good conservative habit and belief.

When Hugh Dalton was given the task of running SOE by Churchill in July 1940, he first had to set out the scope of its activities. In The Fateful Years, he recalls:

As to its scope, sabotage was a simple idea. It meant smashing things up. Subversion was a more complex conception. It meant the weakening, by whatever covert means, of the enemy's will and power to make war, and the strengthening of the will and power of his opponents, including in particular guerrilla and resistance movements.

Subversion was indeed to prove a challenging and controversial concept, and in several instances put SOE on a collision course with the FO and the SIS. Whereas its activities in Bulgaria were limited to formulating and supporting a Partisan resistance movement, SOE's ambitious agenda in Hungary and Romania was nothing less than regime change, with the aim of extracting unconditional surrender from both countries and their irrevocable withdrawal from the Axis side.

The political structures of these south-east European countries were complex and relatively fragile. Bulgaria had been free from Ottoman rule and occupation for just over fifty years; Slovakia had severed its ties with the Czech Lands of Bohemia and Moravia only after the German annexation of its twin sister in 1940 (and, of course, Czechoslovakia, formerly part of Austria-Hungary, had only come into being in 1918); Hungary, given free reign by her Habsburg King and Emperor in 1867 after over 300 years of involuntary servitude to Vienna, found her territories reduced by nearly 60 per cent in 1918 as a defeated member of the Triple Alliance; and Romania, under the suzerainty of the Ottomans until 1878, nearly doubled in size when awarded Transylvania at the Treaty of Trianon. They all had one thing in common chronic territorial insecurity.

Anthony Hope's Prisoner of Zenda, published in 1894, revolved around the fictional state of Ruritania, where the court heaved with intrigue, and plotters abounded. Such fiction seamlessly merged with fact in many instances in the inter-war Balkans where several prime ministers were shot, kings assassinated or abdicated, elections regularly rigged and colonels carried out coups d'tat. It was all very un-British, far removed from Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution. So to this end, I have sketched out the individual political landscapes in the key periods up to the outbreak of the Second World War in order to convey the vivid contrast between British and Balkan political traditions and practices.

Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia were all German allies, though their commitment to the war effort of the Third Reich varied. All had made the decision to throw their lot in with the Axis, unlike the other countries of Europe which had either been forcibly occupied by the Nazis or remained neutral. So any SOE operation mounted within their borders was in enemy rather than enemy-occupied territory, heavily policed by military forces and gendarmerie and populated with suspicious peasants, ever fearful of giving assistance to resistors, if not downright hostile. Furthermore all these states had well-developed and experienced security services, usually supplemented by Gestapo and Abwehr units. This was a far cry from the other Balkan states like Yugoslavia, where a reservoir of defeated soldiers had taken to the hills in large numbers to plot their revenge on the invading Germans and Italians, or occupied Greece, where the appalling famine of 1941/2, together with the ferocity of German response to sporadic acts of resistance, had radicalized much of the population.