Published in 2021 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

Copyright 2021 Sandy Gall

Diary transcription by General Wadud and Ali Nazary

Diary translation by Bruce Wannell, Naser Saberi, Afsaneh Wogan, Wais Akram, Ali Nazary and Charlotte Bonhoure

Extracts from Afgantsy: the Russians in Afghanistan, 197989 by Rodric Braithwaite produced with permission of Oxford Publishing Limited through PLSclear

Extract from An interview with commander Ahmed Shah Masud, former minister of defence, at his base in Jebal Seraj, North of Kabul, on June 28 1993, Sandy Gall, Asian Affairs, copyright The Royal Society for Asian Affairs reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of The Royal Society for Asian Affairs

Extracts from Behind Russian Lines: An Afghan Journal by Sandy Gall reproduced with permission of Pan Macmillan through PLSclear

Extracts from Breakfast with the Killers courtesy of Matthew Leeming. The text was updated for this book by the author

Extract from New Selected Poems by Robert Lowell courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux/ Macmillan

Extracts from Pour lamour de Massoud courtesy of XO Editions

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-1-913368-22-7

eISBN: 978-1-913368-23-4

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by Clays

Introduction

Rory Stewart

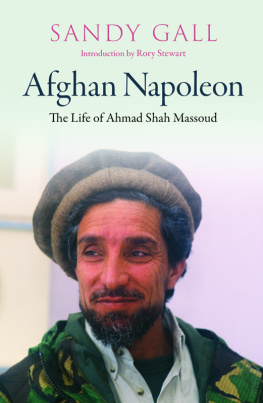

T his is a book about two heroes. The explicit hero the Napoleon of the book is Ahmad Shah Massoud. But the other is Sandy Gall himself. And this is also a story of how an encounter between two heroes can create a new birth in midlife.

Gall opens the book with his two-hundred-mile trek across Afghanistan in 1982 to meet Massoud. He does not explain to us that perhaps one of the reasons he finds it a little tiring is that he is about to turn fifty-six. (I found a similar trek difficult enough at twenty-nine). Nor that, as the book opens, he had already been a reporter for more than three decades. He had reported the Hungarian Revolution and the horrors of the Congo. He had covered the Six-Day War, the Yom Kippur War, Pol Pots Cambodia, and Maos China. He had been detained in Uganda. He had been on the beaches when the US marines were landing in Vietnam on 8 March 1965. And he had been on the Saigon Boulevard ten years later, still reporting a tall figure in a short-sleeved safari suit after the last helicopter flew off the US embassy roof and when the Vietcong tanks were rolling into the capital. He was on the ground reporting the Suez Crisis when Massoud was still an infant.

And, characteristically, Galls modesty extends to underplaying the extraordinary risk involved in walking two hundred miles, with a film crew, into Soviet-occupied Afghanistan. On this trip, he was almost killed, first by mujahideen who thought he was a Russian solider and then by Russians when he was with the mujahideen. One of his cameramen was wounded in Kabul in 1994. Another, Andy Skrzypkowiak, was murdered by Gulbuddin Hekmatyars forces in 1987 as a punishment for reporting on Massoud. War reporting is a tough profession requiring considerable courage. And thirty years as a war reporter could have made Gall very cynical about someone like Massoud. After all, his working life had involved countless interviews with rebel commanders in towns, jungles, and deserts, surrounded by their militias and caught up in the paradoxes of national liberation, communism, modernity, superpower competition, and religion. He had met Robert Mugabe, Idi Amin, and Joseph Mobutu.

And yet the meeting with Massoud changed Galls life. Gall is the beau idal of a Scottish gentleman slender, erect, and dignified; unquestioningly brave; and, under his calm exterior, profoundly romantic. He entered the Panjsher reflecting on the exact cadence of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus rendering of Schubert and Goethes Heidenrslein. He shows a quiet patriotic pride in Gerry Warner, the British intelligence controller who sent an officer to find the Afghan Napoleon, but he also has a resigned realism about the slowness of British bureaucracy in providing anything substantial to Massoud over the following years. He saw much in the Afghan landscape that reminded him of the Scottish Highlands, without the whisky. He found, in this man young enough to be his son, a heroism that seems to have appealed to every fibre of his being. And, at an age when many of his contemporaries were preparing for retirement, Gall found in Afghanistan the central subject of the rest of his long life.

Gall went on to shoot extraordinary films in Afghanistan, capturing unforgettable images of the resistance to the Soviets. This book includes glimpses of his great craft in film-making (Smart was shooting wide open, on fast film stock). He went on to write deeply informed articles and books about the country and then to establish and run a remarkable charity for Afghans who had lost limbs providing aids, prosthetics, and therapy. His wife and daughters in turn absorbed themselves in Afghanistan, living there, dedicating themselves to understanding it, and working with Afghans a tribute, one senses, both to their husband and father and to Afghanistan itself. This book, written when Gall is ninety-three, is part of that extraordinary second life of commitment and absorption that began almost forty years earlier with a long walk across the Afghan hills.

Galls subject, Massoud, is now concealed behind the grandeur of his reputation. His photo twenty times life-size is the first thing you see on arriving at Kabuls airport. The main traffic circle in the city is named after him, there is a national holiday in his honour, and his mausoleum looms over his native valley, larger than the Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae. He is the national hero of Afghanistan. His Soviet opponents praised him as their finest adversary, who, despite very limited international support, managed to hold out for eight years against at least nine assaults by Russias finest troops. And he remained the Talibans most feared opponent which is why they conspired ultimately to assassinate him shortly before 9/11. The American writer Robert Kaplan compared him favourably as a guerrilla commander to Mao Tse-tung and Che Guevara. Others have praised his charm, his keen intelligence, his modesty, his faith, and his deep knowledge and love of classical Persian literature.

And yet, Massoud is also a difficult hero for the modern age. He is not a Gandhi or a Martin Luther King, Jr. Rather than being committed to non-violence, his entire adult life from the age of twenty-two to his death at forty-nine was spent at war, as an Afghan mujahideen commander. So it has never been difficult to point to paradoxes and tensions within his life story, right from his beginning as part of a student Islamist movement that included some of the most radical and notorious figures of the later civil war. Although he moved to the moderate wing of the movement and openly argued for democracy and tolerance, he always remained a mujahid, fighting for Islam as much as for Afghanistan. And although he acquired some notable allies from the majority Pashtun group, many Afghans continue to fundamentally associate him with the Tajiks.